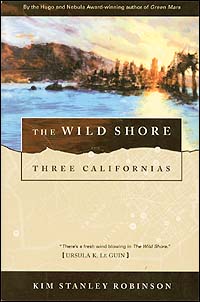

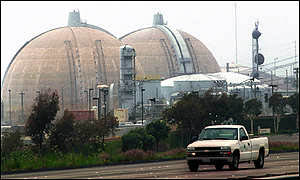

Even in 1984, when The Wild Shore was published (and when, in the story, the bombs went off), the aftermath of a nuclear war was hardly a new theme; it was a staple of science fiction. Walter Miller's A Canticle for Leibowitz may well be the high-water mark of the genre, but even fresher in the mind of Shore's original audience would have been The Day After, which had been a huge media event at the end of 1983. Robinson deviates from the usual formula, however, in that his apocalypse is not a planetwide phenomenon — the destruction comes not in the form of ICBMs but rather suitcase bombs, the US is the only country hit, and it doesn't retaliate, doesn't even know whom to retaliate against. The novel opens 63 years after the attack, with the rest of the world firmly in the 21st century while people in what was once the US, quarantined by an international coalition, have struggled back up to the level of the first American colonists. The action is set in the small community of San Onofre, which is itself sort of a joke: in real life, San Onofre is best known for possessing

The main theme of the book — of all three books in the series, for that matter — is the question: what is the proper scale of a human community? The issue arises in The Wild Shore when some men show up and announce that they've come from San Diego, a thriving community of two thousand people, having secretly rebuilt some train tracks and used a handcart to cover much of the fifty miles to San Onofre. The San Diegans have learned that a resistance movement is developing in the Rockies to fight the quarantine. They want in, and have actually succeeded in killing a few Japanese who have ventured from their base on Catalina onto the mainland. Now they want San Onofre to join up. Opinion is split. Some — mostly the kids, fed on stories of America that make it sound like Atlantis — are all for taking this first step toward resurrecting the US. Others, chiefly the village elders who were actually alive before the holocaust, are opposed. "America's gone. It's dead. There's us in this valley, and there's others in San Diego, Orange, behind Pendleton, over on Catalina. But they're not us. This valley is the biggest country we're going to have in our lives, and it's what we should be working for." Still others point out that in the past, when two villages have allied, it hasn't been long before one has swallowed up the other. They're going to have to choose whether they want to be from San Onofre or from Greater San Diego. This is important, because San Onofre's residents are "newtowners" — they started from scratch in a previously uninhabited valley after the attack. Those who live in the ruins, wearing clothes from and using technology from before '84, they consider "scavengers." Culturally, they don't have much in common with the San Diegans. But, the San Diegans insist, nevertheless, they are all Americans. So what does "America" mean to these people, considering that there is no American government? What do they share as "Americans" that they don't share as Southern Californians? What do the American flag pins the San Diegans wear stand for? "Freedom!" yelp members of the Bush Administration. But actually, as far as personal freedom is concerned, post-apocalyptic America is a libertarian's dream — the international coalition has set no laws, and you can do whatever you want so long as it doesn't involve collective action like rebuilding bridges and stuff. You don't have to pay taxes, you can shake your fist at the surveillance satellites all you like, you can even kill and eat your neighbors if you're so inclined. No, what "America" stands for in The Wild Shore is power, the power of bigness. There's a tug-of-war between the forces that cause states to accrete and those that cause them to fragment. States fragment because the smaller the country, the more control its residents have over their own affairs and the fewer compromises they have to make. And no matter what the scale, you will always find fault lines within a society. Once the British Empire spanned the globe; now it's a commonwealth of 53 sovereign nations (not counting Ireland, Zimbabwe, Hong Kong, or, of course, the US). Once the Soviet Union was a superpower; now it's gone, and the fifteen countries that replaced it are themselves threatening to crack apart further. In fact, name a country, and you'll likely find a secessionist movement therein. Even on the municipal level, you find separatism and factionalism. It happens in big cities — Los Angeles recently had a big vote on whether the San Fernando Valley should become independent — and small: in 1999, I had just moved to Issaquah, Washington, when the northern half calved off and I found myself living in the newly minted city of Sammamish. Even when I was growing up, there was a lot of hullaballoo over whether Anaheim Hills should separate from Anaheim. This sounds ridiculous, but the demographics of the hills and the flatlands are entirely different, so splitting up seems more natural than staying together. But there's a reason that countries don't (usually) dissolve to the point that every house has its own flag. Sovereignty doesn't offer any magical protection. Any group can claim to be a sovereign nation, but unless it can repel invaders (see Russia), that doesn't mean much. Weaker countries have to hope that more powerful ones find it worth their while to keep them from being permanently annexed (see Kuwait); otherwise, assertions of independence are nothing more than words (see Chechnya). Nor is it necessarily wrong to disregard claims of sovereignty; doing so is actually key to the functioning of a state. If you burn down my house, and I call the police, and you claim independence, I don't want the police to shrug and say they can't cross an international boundary to arrest you. Some libertarians might argue that I need to be responsible for my own defense, that "an armed society is a polite society." There are a couple of problems with this. First of all, things escalate; if someone who doesn't like me gets a tank, I need to get a tank. More to the point though, I don't want to have to worry about protecting myself all the time. The Swedes have a concept called trygghet that means, roughly, "security," the assurance that you won't come to harm, and this seems to me like as good a definition as any of what civilization is all about. It's not about feeling safe because you have eighty-three locks on your door and an arsenal in the basement; it's about feeling free to leave your doors unlocked because you know nothing bad's going to happen. Ultimately, the "locks" are at the border and the arsenal's at the naval base. But the rule of law allows violence to be removed from the day-to-day equation of life for most of the citizenry. Establishing this luxury is a big part of why people band together to form nations. But it requires a certain critical mass. So the forces that rip nations apart are balanced, and then some, by those that cause them to band together and grow. Culturally, it might be best if America were dotted with independent city-states, as it is in The Wild Shore — it's kind of silly for Provincetown to be in the same country as Provo. But all it takes is one behemoth to crop up for you to need another behemoth to stop it. Nazi Germany chewed up middling-sized countries like Poland and France; it took crazy-huge nations like the USSR and USA to keep Hitler and company from conquering the world. Patchworks of city-states probably wouldn't have done the trick. Of course, while having a couple of continent-spanning superpowers around probably saved the world in the 1940s, they came close to ending the world a few times in the subsequent fifty years. The problem with being big enough to beat a bully is that you're also big enough to be a bully. "America was great in the way whales are great," says Tom Barnard, the elderly survivor of the '84 holocaust. "America was huge, it was a giant. It swam through the seas eating up all the littler countries — drinking them up as it went along. We were eating up the world, boy, and that's why the world rose up and put an end to us. So I'm not contradicting myself. America was great like a whale — it was giant and majestic, but it stank and was a killer." In real life, America may not be actually forcibly annexing countries, at least not these days, but even before the neocons took power, the US had a long history of toppling regimes it didn't like, installing puppet governments hither and yon, indulging in the occasional military occupation, and helping itself to a disproportionate share of the world's resources — not through outright theft (usually) but simply by being large and powerful enough to dictate the terms of acquisition. (Ask Wal-Mart how that works.) Much as I like the idea of North America becoming a European-style quilt of small-scale sovereign countries, I have to concede that the trend is going in the opposite direction, with Europe increasingly acting as a unified entity just to stay competitive with the US (not to mention China and India, before too very long). Orwell imagined a world consisting of a grand total of three countries; this seems more likely to come to pass than a sovereign San Onofre. One last observation. In The Wild Shore, a surprise attack destroys two thousand American cities and kills about 100 million people, with another 150 million dying in the subsequent post-apocalyptic struggle. In real life, a surprise attack in 2001 destroyed four or so American buildings and killed about 3000 people, but the country reacted as if it were the apocalypse, so I think it makes for an interesting comparison. In The Wild Shore, the grievance ascribed to the attackers is that the US was running roughshod over the rest of the world. Some on the left have suggested that the al-Qaeda attackers had the same complaint. The Bushies, by contrast, argue that "THEY HATE OUR FREEDOMS!" Thing is, though, in this case I think the Bushies are right. It's not just that the US has been dicking around in the Middle East. It's that al-Qaeda is a bunch of religious zealots, and the US is a relatively liberal society that has been dicking around in the Middle East. So anyway, after the attacks, the US was defiant. You might recall that suddenly the entire country was festooned with American flags (made in China) and from the president down to the man on the street, the word was the same: them terrorists thought they was gonna bring down America, but they just made us stronger! We're gonna be MORE AMERICA THAN EVER! And since they hate our freedoms, that meant we were going to become MORE free! More tolerant! More progressive! Right? ...apparently not. Al-Qaeda may not have seen the America as the big bad bully — more the depraved wastrel — but those running the show here in the US did. Because their idea of showing the world what America was all about turned out to be remaking the entire Middle East to suit their own agenda, killing tens of thousands of people, pissing off allies, and torturing the prisoners they'd indiscriminately gathered. And meanwhile the US electorate has put into power a growing cast of home-grown religious zealots to whom al-Qaeda may be an enemy team, but one playing the same sport: "my god is bigger than yours." It's the sort of thing that makes you want to round up 59 of your closest friends and secede.

Return to the Calendar page! |