|

|

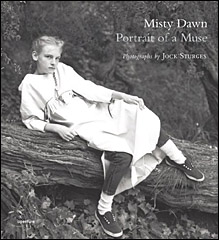

Misty Dawn

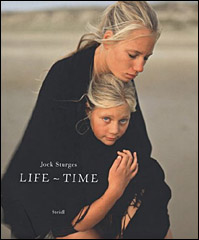

Life-Time

Jock Sturges, 2008

It’s an election year, so I’d hoped Jock Sturges might have another book coming out like he did in ’00 in ’04—and was jazzed to discover that he was actually due to release two within a few weeks of each other. I now have both.

Before I get to them, a quick recap of what Sturges’s previous books have been like. Sturges has made a career taking photographs which, by his own description, “really are little more than family pictures made with a fine art technique”. Every year he has taken another batch of photos of the same families—naturally, there are additions and subtractions, but from year to year there’s a lot of continuity—on the beach at Montalivet, France, and in a tiny community in the wilderness of Siskiyou County, California. And every few years one publisher or another has put out a collection of some of the photos he’s taken since the release of the previous book. The organizing principle of these collections has not always been obvious, as they have tended to skip forward and backward in time and from one subject to another, like someone wandering around a museum without looking at the map. But if you gather several of the books together, and follow one particular subject’s progress from one year to the next, you don’t just have art—you have sequential art. The pictures turn into a narrative: you watch chubby toddlers turn into stick-thin children, who then develop curves and after that develop confidence… it’s really quite a thing. It always struck me as a shame that the publishers insisted on working against the narrative. If only one of them would put out a book that selected a single model and followed her from preschool to adulthood in chronological order!

With Misty Dawn, that book has arrived. If you’re going to get one Jock Sturges book, this is the one to get. It’s as if after releasing a number of poetry collections with a few short stories included, Sturges has finally put out a novel—one continuous narrative that takes up the whole volume. Nor is it merely a reordering of stuff we’ve seen before: it’s split about 50/50 between the classics and photos that hadn’t before appeared in print. What’s especially great is that the previously unpublished material is of the same caliber as, and often superior to, the stuff that’s shown up in earlier volumes. (Page 75, for instance, is a picture of Misty at about age 14 out in an overgrown field with the rusting hulk of a giant truck cab and a battered traffic sign. I’ve seen several slight variations on this photo before; I prefer this new one!)

A month later Life-Time came out, and in a sense it’s much closer to the collections of old: turning to a random page, I find that the chronology goes 2004, ’05, ’04, ’03, ’05, and covers four different subjects within that stretch. Again, this deemphasizes the narrative, encouraging the reader to take in each photo not as a step in a series but as a solitary work of art. And, yes, as solitary works of art, some of them are magnificent—page 51 is itself worth the purchase price of the volume—but to me no single photo has nearly the power of the simple fact that the small child on page 37 is the woman on page 149. We’ve heard a lot about change this year, but what could be a better reminder than these two pictures that Erin Winters is right, that things are always changing, that there are no frozen moments, that everyone you look at is changing before your eyes, that people aren’t nouns but verbs? But this is why presentation is important. One of the lessons I’ve had impressed upon me during my brief stint as a screenwriter has been that the primary tool of film is the cut, which invites the audience to participate in filling in the gaps in the narration. That goes for any sort of sequential art: much of the power of the medium lies in what Scott McCloud has called the “dance of the seen and the unseen”. But the organization of Life-Time and its predecessors can make these sorts of revelations seem almost accidental.

Where Life-Time differs from Sturges’s other books is that it’s a gigantic tome entirely in color. Rich, hypersaturated, eye-popping color—you really need to see the crazy sapphires these kids have for eyes, or the impossibly hypnotic green that shows up on page 101. This is where the “fine art technique” earns equal billing with the “family portraits”: in most of these photos Sturges uses a limited palette, arranging a handful of strong colors in a manner not entirely unlike—and with about the same hit rate as—Piet Mondrian, so naturally I love it. The colors are so gorgeous that they make me wish I could go back and have all the Misty Dawn photos reshot in color. Which raises the question: why was Sturges’s early oeuvre in black and white in the first place?

Sturges has said in the past that shooting in monochrome was intended as a sort of distancing technique, that it allowed the viewer to see not just a collection of discrete objects, not just this person or that, but abstract qualities: Innocence, Grace. Similarly, the sumptuous hues of the color photos signal that this is not photojournalism you’re looking at and that you should therefore fire up the art-viewing centers of your brain. But I’ve always been somewhat dubious about this distancing business, and reading the text piece at the end of Life-Time crystallized why. Sturges writes:

Why are the models nude? […] Clothed portraits are pinioned by fashion to specific moments in time and become as much, if not more, about culture than the people depicted. Those clues are absent here and thus one is left considering more essential states.

I’ll buy about half of this: it certainly makes sense to me that if you care about clothes you take pictures of clothes and if you care about people you take pictures of people. But I don’t agree with the suggestion that nudes are somehow unpinioned from time and space, nor do I really believe in the existence of “more essential states”. There is no Sein apart from Dasein, no “being” apart from “being-in-the-moment”. Clothes may be loci of culture… but we are loci of culture as well, clothed or not! Each of us is a locus of biology and history and sociology and frickin’ geography playing themselves out. What makes Misty Dawn Johnson so fascinating is not just her Pre-Raphaelite features or any sort of ineffable spark but the fact that she’s a Sawyers Bar Grizzly. Not just that we get to watch her grow up, but that we watch her grow up surrounded by this echoing wilderness halfway between Eureka and Yreka. One of my favorite of the new pictures in the Misty Dawn book shows her stroking the face of a horse while behind her is an ominous sky and a hundred miles of mountainous wasteland. It reminded me of driving through the Canadian Rockies early one morning and seeing, just on the other side of a fence along the roadside, a pretty, dewy-faced girl of about thirteen, in a puffy jacket and knit cap, walking a malamute. I thought, what must it be like to be her? To grow up here, in a village of maybe forty people, twenty miles from anywhere else, a sort of modern-day oread, and yet to be every bit as real as I am, to live on the same planet, to get the same sitcoms beamed in via satellite, and yet again to look out your bedroom window and see nothing but uninhabited mountains between you and the north pole?

The two best things about getting Ready, Okay! published were that I got to talk to Marie Martin again and that Jock Sturges invited me over and let me pick out a photo to take home. The photo I picked—still unpublished, I am secretly pleased to be able to say—is of Misty Dawn, but it’s every bit as much a landscape: she’s perched upon an outcropping of smooth dark rocks, a stretch of whitewater crashing behind her, a leafy branch dangling into the upper left corner of the frame. And while she isn’t wearing anything, this is still a picture of culture: the culture of the Salmon River, circa 1988. That’s a big part of what makes it so beautiful.

|

|

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tumblr |

this site |

Calendar page |

|||