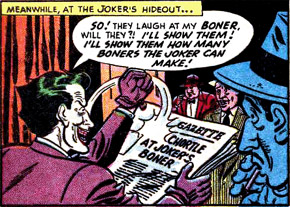

Jonathan Nolan, David S. Goyer, Bob Kane, and Christopher Nolan, 2005 #5, 2008 Skandies Okay, so if I recall my years of cultural studies classes correctly, the question you're supposed to ask after you watch something like this is, "What anxieties does it reveal?" Batman has long been an emblem of anxiety about urban decay — sort of a fictional "white fight" counterpart to postwar white flight. One of the most striking images in Batman Begins is the contrast between the clean monorail train packed with wealthy riders that Bruce Wayne remembers from his childhood — built by his father "to unite the city" — and the nearly empty, screeching, graffiti-ravaged hellcar on which the Katie Holmes character is so clearly in danger of losing her purse or something worse. (Having been mugged on the Chicago El, I know the feeling.) Interestingly, the main villain of Begins, Ra's al Ghul, is basically a goateed version of Philip Wylie, arguing that the city must be destroyed in order to save it; Batman takes the anti-apocalyptic stance that the city can be cleaned up without being leveled. The other main anxiety expressed in Batman Begins is fear of corruption: the idea that not only is crime everywhere — crime, crime! — but that it has co-opted the institutions that are supposed to fight it, from the cops to the courts to the government. The drama in The Dark Knight is supposed to derive in large part from the question of whether Batman's efforts have been sufficiently successful that, instead of resorting to Batman's guerrilla tactics, someone like district attorney Harvey Dent can take on the crime bosses in the light of day without suffering adverse consequences. (Of course, anyone who knows their Who's Who in the DC Universe knows what the answer's going to be.) Then there's the Joker. Obviously there's a lot of noise in the trajectory I'm about to suggest — different villains have traveled along it at different speeds, retrogressed from time to time, etc. — but it seems to me that supervillains in general have tended to follow a certain course. Initially, they were basically bank robbers — often literally, though I recall that more often they were after some sort of exotic trinkets. A few wanted to rule the world, but that was more a matter of pursuing a different means to the same end, i.e., an extravagant lifestyle. But then writers became interested in exploring the villains' psyches, and in so doing, tended to give them more sympathetic aims and a sort of nobility. Dr. Doom wanted to rescue his mother's soul from hell; the Kingpin had a sick wife; Magneto was a Holocaust survivor who wanted to protect his people from another round of genocide. Literally hundreds of villains went straight at one point or another. Then came a backlash and a third wave of supervillain portrayals. Now they weren't flashy thieves or misunderstood anti-heroes, but psychopathic maniacs whose only motivation was their glee in others' suffering. They were, in short, Evil. During Batman's "BAM! POW!" era, the Joker was just one of many bad guys who liked to pull wacky heists. In the '70s he returned to the homicidal ways he'd exhibited in the '40s, but even as late as Alan Moore and Brian Bolland's The Killing Joke (1988), we see an attempt to humanize the Joker: though there's a line about the Joker's "multiple-choice past," it seems pretty clear that we're supposed to accept as his true origin that the Joker was a very small-time crook who went insane after his wife and unborn child died in a random, stupid accident — criminally insane, yes, but still, legitimately bonkers, not simply evil. The Dark Knight isn't having any of that. Its Joker is a third-wave villain who tells the story of his past — a different story every time he tells it — solely in order to mock the very idea of an exculpatory background. This Joker is nobody, from nowhere, just an "agent of chaos," a "dog chasing cars." Here's the problem. Much of The Dark Knight is about the lengths to which we should or should not be willing to go in order to deal with enemies like this. Enemies who come up with high-profile destructive stunts designed to make people feel like they're being toyed with. Enemies who manage to pull off these stunts with "a few drums of gas and a couple of bullets." Enemies whom we have to cross ethical lines in order to pursue — secretly surveilling the entire populace, for instance (though promising to stop once the threat is over). The Joker, in short, is this film's idea of a terrorist. But terrorists aren't just agents of chaos who kill for anarchy's sake! Terrorists have grievances. In the case of al-Qaeda, the grievance is that the United States, which spends more on the military than the other 95% of the world combined and has military bases in 130 countries, is the chief obstacle standing in the way of the imposition of sharia law. You might find this grievance illegitimate, just as you might the grievances of Hamas or Hezbollah or whatever group happens to be in the news this week, but pretending they don't exist is stupid. I wonder whether the move in comics away from bank robbers and toward deranged sadists might not be a form of wishful thinking. Because, sure, there are psychopaths in the world, imprisoning their inbred children in basements and what have you. But on a systemic level, they don't do as much harm as the much more banal evil we face today. The evil we face today is a class of people who don't mind the tent cities springing up in places like Sacramento so long as they get to live on leafy estates in New Canaan; who shrug at the news of food stamp enrollments reaching new records as they book their reservations at Masa; who react to IMF warnings of depression-fueled unrest overseas by moving their vacations from Aruba to Aspen; I could rattle off as many stereotypes as you like and they'd all be true. Maybe not for everyone, but for enough to keep CNBC in business. And, yeah, it's pretty boring that the global economy has been brought to the brink by people motivated by nothing more complicated than a desire for an extravagant lifestyle. They're not tortured souls like Two-Face or implacable and incomprehensible like the Joker. They're Silver Age bank robbers; they've just discovered that the bank is easier to rob with a contract and a desk than with a gun and a getaway car. And I wonder how different any of us are, for that matter. I get disgusted when I read Wells Fargo execs whining, without irony, "Come on Obama, do the right thing for all Americans, not just those who make <$250k per year" when threatened with the possibility of having to pay 3% more on that overage in order to help bring the US up to a civilized standard with decent schools, a functioning health care system, and cleaner energy. It seems to me that once you've reached a certain level of affluence you should be satisfied. But of course most people in the world would say that I, even as I feel like I'm living at close to a subsistence level in my little studio apartment in this crummy chunk of suburban sprawl, am way over that line. I make about six times as much as the world's average income — fifty times the global median! I have all sorts of crazy luxuries like clean water on demand and an air-conditioned vehicle reserved for my own personal use, and while I wouldn't mind paying higher taxes in exchange for the sorts of services social democracies provide, I'm not volunteering to give away 83% of what I currently bring in. Like everyone else, I've been conditioned to think of my circumstances as no better than what I deserve. I do think that they are no better than what everyone deserves, but if those "ecological footprint" sites are right, bringing the rest of the world up to this level isn't currently possible. The American military bases in 130 countries suggest that the ecological footprint sites are correct. The Joker's first target in The Dark Knight is a bank that turns out to be a front for the mob. And the Joker's supposed to represent terrorism, right? Meaning that while the U.S. is eventually represented by Gotham City as a whole, it is first represented by the mob bank. Now, that part seems fairly accurate to me — isn't the Third World's most direct experience of the U.S. the infrastructure it has in place to swipe local resources and funnel them back to the rich? But once that piece clicks into place, the rest of the movie falls apart. For it makes sense that in parts of the world where people lack purchasing power, contingents will impose social systems that allow them to exert other kinds of power: patriarchy, rule by decree, your usual fundamentalist hallmarks. And it also makes sense that people who imbibed that ideology would, quite apart from any economic grievances, come to "hate our freedoms," as the saying goes. Osama bin Laden may have wanted to provoke the U.S. into an attack on a Muslim country, hoping in turn to unite the Muslim world in opposition to American hegemony. The foot soldiers have probably been working on more of a "my god is bigger than your god" level (you know, like American generals). But in both cases, their origins and aims are comprehensible. The autochthonous, nihilistic Joker is a pretty lousy metaphor for either. (And, come on, to dig out the old Prisoner's Dilemma for your big climax? How much philosophical weight were the filmmakers hoping to get out of a staple of sixth grade classes?) So back to the idea of corruption. It's easy to see why terrorism might be on the minds of '00s filmmakers, but to what extent does corruption tap into the contemporary zeitgeist? Digression: over the past few years, Marvel Comics has published a number of huge crossover events that have changed the status quo of its superhero universe. First, a group called the New Warriors took on a villain who exploded, killing them and hundreds of civilians. This led to a superhero registration act that caused a rift between those who were happy to register with the government (revealing their identities and agreeing to work on its behalf) and those who preferred to remain vigilantes. The two sides came to blows, and Tony Stark (Iron Man) led the pro-government forces to victory; he was rewarded by being appointed director of SHIELD and de facto leader of America's superheroes. He launched an initiative to place government-sponsored superhero teams in each of the fifty states. However, under his watch the superhuman community was infiltrated by the shape-shifting alien Skrulls, who proceeded to invade the earth. So after the invasion was beaten back, Stark's post was turned over to Norman Osborn, the so-called "Iron Patriot," who is actually the supervillain known as the Green Goblin and brought in a cabal of fellow villains to more or less rule the world. This naturally made a number of commentators wonder: isn't Marvel out of step here? Why have charismatic hotshot Tony Stark turn over the reins to gruff hardliner Norman Osborn just as, in real life, Dick Cheney's crew was being booted out in favor of Barack Obama? Sure, there are a few kooks out there who think Obama is secretly a supervillain — and most of them seem to spend their time posting messages to this effect in the comments section of abcnews.com — but to everyone else it sure seemed like Marvel was getting it backwards. Now back to The Dark Knight. My first thought, watching this movie in March 2009, was that the film's anxiety over the prospect that those charged with the task of fighting crime are actually in league with the criminals sounded awfully familiar. Isn't that what we're seeing with the financial crisis? The dominant theme this weekend from the economists who haven't been wrong about everything was despair. It seems that Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner has a plan to funnel even more money to the people who tanked the economy in the first place — not to save the economy as a whole, but in order to keep the current grotesquery of a banking system in place as the rest of the economy collapses. And not just the system, but the people within that system. Why? Well, because they're Geithner's pals, and those that aren't are at least of his class. And that raises a pretty obvious question: why the hell did Rackie-O stuff his economic team with members of the very same Wall Street fraternity that got us into this mess? As Duncan Black and others have pointed out, there's a sense that Wall Street is an elite brotherhood of the best and the brightest, with keen financial minds working far above our ken... and it's just not. One of the things I do for a living is teach the GMAT, the business school admission test, and you'd be surprised at how many of these shiny new MBAs being handed accounts worth hundreds of millions of dollars were, two years earlier, in classes like mine learning how percentages work. And the firms they join are full of gamblers, swindlers, moral infants, and that's not a coincidence: that's the job description. Choosing to work in finance amounts to saying, "Nah, I don't want to actually produce anything; I just want to take crazy risks with other people's money and skim as much as I can off the top." And yet even after people vote for change — because of the financial crisis, remember, for it was only after the big emergency in September that Obama pulled ahead in the polls — insider status on Wall Street is still somehow seen as a plus. Because that's what we wanted, y'know. We were crying out for Commissioner Penguin to be replaced by Commissioner Riddler. But like I said, this is as anachronistic as Marvel's Dark Reign arc. In March of '09, naturally the financial crisis is going to spring to mind when you're watching films that are obsessed with bad guys infiltrating the institutions that are supposed to be keeping a lid on them. The filmmakers would have had to be pretty prescient to be thinking along the same lines back in '07, though, so I wonder what they actually did have in mind.

Return to the Calendar page! |