Olivier Assayas, 1996 #5, 1997 Skandies Well, hell, I dunno. This is a movie about an aging French director who's doing a remake of a silent-era serial about vampires. Happening to catch a Hong Kong action movie, he decides that Maggie Cheung is perfect for the lead role and summons her to Paris. (Since she doesn't speak French, this means that most of the movie consists of people speaking English to her een zees out-raizh-eous accent.) Various things happen. Maggie is poured into a skintight black catsuit and shoots a few scenes. The costume girl develops a crush on her. The director has a nervous breakdown. A lot of it seems to be about the state of French cinema in the mid-'90s, which would be more interesting to me if I were French, interested in cinema, or living in the mid-'90s. (Actually if you were to listen to my MP3 player you might be forgiven for thinking that I was living in the mid-'90s.) Mike D'Angelo wrote in his retrospective of 1997 that "I think that my review of Irma Vep was the worst piece I wrote all year [...] whatever limited critical faculties I possess are completely disengaged, and I'm reduced to pointing at the screen with a wild-eyed, gleeful expression." Meanwhile, this paragraph is quite possibly the worst piece I've written in 2009, and I'm reduced to pointing at the screen with that slightly nonplussed but passably entertained expression that signifies that I'm probably going to give the movie a 3.

Bad Machinery Last September cartooning man John Allison brought his webcomic Scary Go Round to a close after seven years, starting up a new project called Bad Machinery. This was not unprecedented: Scary Go Round was itself a reboot of Allison's earlier comic Bobbins. In both transitions Allison shuffled certain characters to the background and pushed others forward, while subtly changing genres. Bobbins was a sitcom set at a magazine office, which gradually got wackier the way sitcoms do (Urkelbot, meet Unit Daisy); Scary Go Round dropped the office setting and explicitly added elements of supernatural horror to the mix, but on both sides of the divide you had Shelley and Amy and Fallon and Ryan and Tim and their zany antics. Similarly, as Scary Go Round unfolded, the focus drifted from the Bobbins alumni, now in their late 20s, to younger additions to the cast — first teenagers, then little kids. So it was a pretty smooth transition to Bad Machinery, which despite its title is actually about those kids, now eleven years old, and the rivalry between the girls and the boys over which of them make the best amateur detectives. The problem is that apparently the switch to a new title has driven off half of Scary Go Round's audience. Allison, known for his graphene-thin skin — he has torn down the comment areas on his site on no fewer than three separate occasions upon discovering a negative remark — had a bit of a meltdown about this on his blog, posting laments and a series of "Crisis Centre" cartoons. The problem? Based on the feedback he'd received, Allison concluded:

And again:

Many of the replies seemed to bear this out. A sampling:

A few more data points. One commenter told Allison that "Your strong points in SGR were your characters." So which characters from Scary go Round did the Bad Machinery detractors miss?

A more trenchant observation on Allison's part is that "What always interests me is how readers will invest the most paper-thin characters with things that I never saw in them. You may laugh but to me, Desmond was an infinitely more rounded character than The Boy, who was pretty much just a cipher." For those unfamiliar with SGR, "The Boy" is the nickname of the Eustace mentioned above, and yes, he's pretty much a generic geek boy who wound up dating Esther, who herself is little more than a sort of off-brand Emily the Strange. Desmond, by contrast, is an infantile, cowardly, tantrum-throwing creature with green scales, webbed hands and feet, and a taste for the high life. Allison's assertion attracted the following reply:

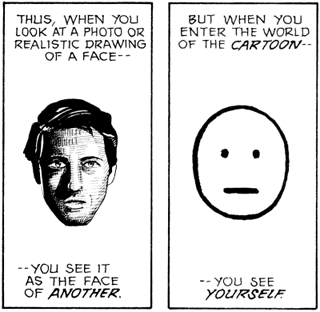

First, that's not what "conversely" means. Second, what better illustration could there be than the paragraph above of Scott McCloud's maxim about reader identification?

Here we're talking about shallow characterization rather than sketchy art, but the principle remains the same. This guy looked at a cipher who didn't even have a name other than "The Boy" for the first three years of his existence and thought, "My Lord! That's—that's me!" And is aware of it. And wants more. Doubly interesting are his assumptions about the role of identification in authorship. I can't speak for John Allison, but personally, I can't really write a character I don't identify with. Now consider my current project, in which one of the characters is a hardcore urbanite and another is all about suburban bliss. Which one do I identify with? Whichever one I happen to be writing at the moment! When the former whistles merrily as he strolls home five blocks from the downtown farmers' market, a bag of organic persimmons and chanterelles slung over his shoulder, passing the public library and his daughter's charter middle school along the way, that's coming from the guy who grew up stranded in a blotch of Orange County where lacking a driver's license was tantamount to quadriplegia. When the latter sighs with contentment as she sinks her toes into the plush carpeting of her exurban McMansion and smiles at the unspoiled mountain vista that greets her through the window, that's coming from the guy who feels like he's strangling when he's on a street corner surrounded by dilapidated apartment buildings and can only see the surrounding hillsides through a sieve of overhead cables. I am large, I contain multitudes. And I'm old enough to know that this is okay. What I think Allison discovered is that a fair chunk of his audience was still of an age when people consume media in large part for identity reinforcement. This can mean finding role models for the identity you've decided to adopt: Taxi Driver is a good movie, but the reason I watched it 22 times when I was 17 was not for its quality but rather to nail down my newfound sense of myself as an outcast in a sick, corrupt world. Similarly, it appears that zine girls and the geek boys who love them gravitated to Esther and Sarah and The Boy, and that a few years earlier a fair number of twentysomethings who had whimsical conversations in bars found "alterselves" in Shelley and Amy and Ryan. And note that a lot of identity reinforcement is aspirational: they may have seen themselves in Shelley and Amy and Ryan in that those are the sorts of friends they'd like to have had, in a world where not too many people are clever enough to sound like John Allison is scripting their dialogue. So why would these SGR fans be alienated by Bad Machinery? Because children are exactly what they don't aspire to be! They just finished slamming the door screaming, "Mom, I'm not a kid anymore, god!" Spending quality time with Shauna and Lottie undermines that message. What's more, identity reinforcement through media is not just a matter of finding a mirror to look into. Subcultures define themselves to a great extent through media choices. And while Allison may assert that "My older friends genuinely can't see the difference between the new comic and the old" — and I, being roughly his age, agree — much of his audience is significantly younger and at the age when people will in all seriousness insist that "I'm not emo, I'm scene" while holding up two identical pictures. So what a lot of these folks object to is not the focus on children so much as the subtle change in genre. Example:

"I don't want to make the kind of comics you want to read any more," Allison told these people. "My old style was too heavy on standard webcomic tropes and creative returns were fast diminishing [...]. I grew up with Roald Dahl and Tove Jansson and Richmal Crompton and Ronald Searle. They were all masters of world-building and immersive stories. They never spoke down to readers and I can read a lot of their work as an adult with the same pleasure. If I want to keep doing this for the rest of my working life, I have to make something lasting like that." That announcement in and of itself, both in its repudiation of the monkey robot people and its ambition to create works of lasting value, makes me want to support Bad Machinery. Unfortunately, I have to admit that so far I too am a little disappointed. Not because it broke with Scary Go Round. More because it didn't. Take characterization. Here is how the cast page of Bad Machinery describes Charlotte Grote:

The problem is that, by the end of its run, pretty much every character in Scary Go Round could be described this way. As I mentioned in my minutiae, it says something that Allison systematically weeded out voice-of-reason characters such as Tim, Riley, and Erin, and replaced them with ever sillier clowns: Desmond Fish-Man, Carrot Scruggs. Bad Machinery has been running for over two months now and I'm still waiting for some sort of distinguishing feature that will allow me to tell Charlotte's dialogue apart from Shauna's without looking at the tails on the speech balloons. Allison has done a little better with the boys, insofar as I can tell Linton from the others based on the fact that he sounds reasonably sensible. But that probably means that, like the last character in Allison's work who could find her ass with both hands, he'll probably be sent to hell. And other than Linton, so far it's "standard John Allison character, blonde hair," "standard John Allison character, black hair," "standard John Allison character, messy hair," etc. As for the art, again, I want to support Bad Machinery simply for having some. As Allison has pointed out more than once, the most popular webcomics these days seem to involve stick figures, so it's nice to see someone who's actually interested in the "art" side of "sequential art." But while Allison has mentioned on his blog that "I started drawing like I wanted to" in mid-2008, those who follow my minutiae may recall that I have been muttering about the decline in Scary Go Round's art for some time now:

I do wonder how Allison can look at the '08 face there and seriously argue that it's superior to the '06 and '04 versions. That is just preposterous to me. And it's not an anomaly. Thus far the art is not a huge selling point either. So I've found myself wondering why I've stuck with Bad Machinery as half the SGR audience has apparently checked out. If it's not for ninja pirate jokes or to live vicariously through The Boy, and not for the characters or the art, what is it? The obvious question to kick off such an inquiry is why I started following Scary Go Round in the first place. The answer is that I followed a link from Scott McCloud's blog to a cartoon in which a girl with purple bangs and tattoos related that, at the job interview she'd had that day, "I told them the hair and the ink were injuries sustained during an explosion at the purple factory. 'It started off explodey... and then it got explodier!'" Browsing the archive, I found that nearly every strip had dialogue like this. An elevator operator, in response to a floor request: "I almost killed a man once. He took my umbrella, and it was pouring with rain. I just couldn't stop hitting him. Then the police came. Top floor." Tessa on a fifteenth-year senior at her university: "He's an eternal student. He can't deal with a world where girls aren't 19." However, the level of verbal genius on display in Scary Go Round tailed off almost immediately after I started following the comic, and realizing this got me wondering how it is that clever repartée that I read in 2003 still has me checking in at nine o'clock sharp four days a week in 2009. But then it occurred to me that this isn't even the most telling example of the extent to which this sort of linguistic dexterity can turn my head. Because when I think of people who can turn a hilarious phrase, there's one who springs to mind before even John Allison. A few of her sentences appeared on my screen in 1999. They were really funny. And my makeup is such that I really had no choice but consequently to date her for six years. By those lights, three minutes a week is not a big ask. Addendum 2010: I am pleased to report that Bad Machinery #2, "The Case of the Good Boy," is very good! I've written a new article on Bad Machinery to discuss how it's improved.

Return to the Calendar page! |