|

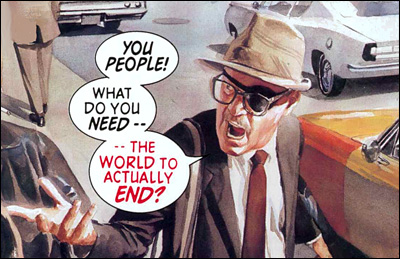

Astro City: The Dark Age Kurt Busiek and Brent Anderson, 2005-2010 There was a time when no one questioned the superheroes. Superman flew around foiling crimes and stopping natural disasters, and no one worried about the presence of an all-powerful alien among us. Batman operated as a one-man army, and the police and citizenry gave him a big thumbs-up. Then the '60s arrived and Marvel Comics changed things. The Amazing Spider-Man presented a world in which the local newspaper asked whether the title hero's vigilantism made him a threat or a menace. The X-Men put forward the notion that no amount of heroics could keep the public from being scared of those with abnormal and potentially threatening abilities. And that seems to drive Kurt Busiek up the wall. Busiek first made a name for himself with Marvels, a fully-painted limited series from 1994 that depicts seminal events of the early Marvel Universe from the perspective of the man on the street. For instance, we see the battle between the Avengers and the Atlantean warlord Attuma from Avengers #26-27 reduced to ankle-deep flooding at the local zoo, some sketchy reports on the radio, and a guy with a sandwich board wailing about Judgment Day. This emphasis on the experience of civilians naturally raises the question of how those civilians react to the superheroics that dominate the news in their world — and Busiek seems not to care much for their reaction. Take the issue that tackles the arrival of Galactus. For page after page, we witness people freaking out at what is clearly the end of the world... praying that the Fantastic Four can somehow accomplish the impossible and prevent the apocalypse... and when they do, the everyman narrator Phil Sheldon reflects, "You would have expected us to canonize the Fantastic Four — to raise statues in their honor — name bridges and mountains after them [...]" Instead, he fumes, people grumble that the F.F. hadn't acted sooner, or speculate that the whole thing was a hoax. "The whole city seemed embarrassed somehow — ashamed of their terror, now that it had passed and they were still alive. And they were [...] blaming the Marvels for the fear they'd felt." Finally, Phil snaps:

At the time, it seemed like an interesting story — but just one story out of many, not necessarily any closer to Busiek's heart than any of his others. Nor did the character seem like he was necessarily speaking for Busiek. But this has turned out to be a well Busiek has returned to repeatedly. The big plot thread running through his tenure on The Avengers, for instance, was about a sinister organization ginning up protests against the team, leading Thor to quit in a huff: "I will not [...] beg jackals that I might continue to have the privilege of safeguarding them!" And now we have The Dark Age, a 16-part, five-year storyline in his Astro City series that covers the same territory once again. One of the most acclaimed elements of Marvels was the way it grounded Marvel continuity in real history; all over the comics world people slapped their foreheads and said, "You mean all this time Galactus was a metaphor for the Cuban Missile Crisis and I never noticed until now?" That may not have been Lee and Kirby's conscious intent, but they were tapping into the zeitgeist of the time. The Dark Age runs from 1972 to 1984, when the zeitgeist was different and comics reflected it. By the early '70s, not only were people in these stories challenging whether superheroes were good for anything, but the heroes found that they couldn't make a very good case for themselves. At DC, Denny O'Neil had Green Lantern intervene on behalf of an apparent mugging victim who turned out to be a slumlord, prompting one of his tenants to ask why the spacefaring hero "helped out the orange skins" and "done considerable for the purple skins" but "never bothered with the black skins" — and Green Lantern has no answer but to hang his head. At Marvel, Steve Englehart had a group called the Secret Empire try to destroy Captain America's image, and at first Cap whined about it: "I've done almost nothing except [...] to help my fellow man — and what happened? Lots of them — lots of them — turned on me [...]"; then it turned out that the head of the Secret Empire was Richard Nixon ("High political office didn't satisfy me! My power was still too constrained by legalities!") and Cap decides that his critics were right and that "everything Captain America fought for" was in fact "a cynical sham." By the end of this period, Cary Bates had DC's Flash go on trial for killing a supervillain — and Busiek kicks The Dark Age off in similar fashion, with the straight-arrow Silver Agent shooting dead the (ahem) Maharajah of Menace, eventually getting executed for his crime (in 1973, the year the murder of Gwen Stacy marked what is now considered the semi-official end to the Silver Age). Now, as noted in the pop-up a couple of paragraphs above, Busiek likes his stories insanely busy, so this Silver Agent thread is just one among many. But the overall thrust of the work is that what made this age Dark was that people started criticizing their noble protectors. On the title page of the first issue, people in a bar watch the Silver Agent on TV announcing the capture of the L.S.Deviant, and a woman grumbles, "Why couldn't they have stopped it sooner?" The Experimentals wreck a building in the process of stopping the Micron Army, and the people who live there shout, "Look what you done to our building! Our homes! LOOK at it! Where you think you get off, just blowin' apart people's homes like this?" To which one of the Experimentals shouts back, "We saved your lives [...] an' maybe we coulda fixed your stupid building [...] but if this's what I get, nearly killin' myself to save your sorry hide an' millions of others — forget it!" And at some point you have to conclude that, y'know, you just don't return to a theme over and over again like this if it isn't important to you. It seems pretty clear from all these stories that Kurt Busiek is disgusted by distrust of superheroes and infuriated by ingratitude for all their sacrifices. Oh, and by the public's hypocrisy, as when danger strikes (e.g., Madame Majestrix attacks) everyone goes crying to the superheroes to save them. And given that Busiek built his career on the notion of the superhero as metaphor, I have to wonder... what is all this a metaphor for? Cops? Soldiers? Government officials? I mean, it'd be one thing if Busiek echoed these sentiments in real life, as Britney Spears did when she said in 2003 that "we should just trust our president in every decision that he makes and we should just support that, you know, and be faithful in what happens." But, having read years' worth of posts by Busiek in various online fora, I know that this doesn't square at all with his politics, which are moderately but unapologetically liberal. Seriously, I would love to be able to say that the next paragraph of this article will be a brilliant resolution to this seeming contradiction, but the fact is that I just don't get it. There is a weird mismatch between The Dark Age and the era it purports to comment on. See, the point of those Green Lantern issues was that he had been in the wrong all those years, protecting the interests of the power structure while doing nothing to alleviate the plight of those in need. The point of those Captain America issues was that he had been deluding himself all those years, thinking that America embodied the noble ideals he fought for. As for the Flash — he had killed the guy! Maybe it was justifiable homicide, as the Reverse-Flash was about to murder Fiona Webb, but he didn't have to kill him to stop him, and he did. But Kurt Busiek's Silver Agent... no, he'd been mind-controlled, and the Maharajah he'd supposedly killed had been a "bio-decoy." I.e., he was completely innocent, and that we ever could have doubted him was, as the inscription on his memorial says, "To Our Eternal Shame." And that is a plot, not from those supposedly dark days from 1970 to 1985, but from, like, 1962. You can argue that the point is that of course the Silver Agent has a Silver Age excuse, and that his execution therefore represents the end of a more innocent era... but my point is that that is an uncharacteristically anti-progressive message. The Silver Age was not a more innocent era; it was the era of Jim Crow and John Birch, of HUAC and DDT and MAD (the Cold War doctrine, not the magazine). And the years that followed were not when what Trent Lott called "all these problems" started. They were when people woke up to the fact that these problems had been endemic in American society for decades. So why condemn them? The Dark Age in Astro City's chronology officially ends in 1986, when Samaritan arrives and saves the space shuttle Challenger, launching an era of renewed trust in superheroes. This is interesting in that it means that the history-minded Busiek is diverging from history in two ways. The first is, of course, that in real life the Challenger blew up, which in Astro City means that we are now headed toward dystopia. The second is that in the real 1986, limited series such as Squadron Supreme and Watchmen took the trend of the "Dark Age" even further, moving beyond stories of self-doubt to suggest that distrust of superheroes was well-founded, even when the supposed heroes themselves didn't agree. Given that Busiek's extras get shouted down by more important characters when they express such sentiments, I suppose it's not surprising that he found an alternate happentrack more to his liking.

| |||||||||||