Hamlet

HamletWilliam Shakespeare and Kenneth Branagh, 1996

#9, 1996 Skandies

Romeo + Juliet

William Shakespeare, Craig Pearce, and Baz Luhrmann, 1996

If you've been reading my site for a while you already know what I have to say about Shakespeare. The short version is that he is revered primarily for his dexterity in a dead language, viz. Early Modern English. Both of these films attempt to update Shakespeare in all sorts of ways. Luhrmann's Romeo + Juliet updates the original play to a late-20th-century Miami on steroids, shot in a way that tries to out-MTV MTV and set to the strains of Radiohead and the Cardigans. Branagh's Hamlet updates to an ahistorical version of 19th-century Europe, and, while full of quick cuts, isn't quite so hyperkinetic. Instead, it puts its bravado into going big: the full text of the original play, running over four hours; gorgeous 70 mm photography; bizarrely miscast but attention-grabbing movie stars in cameo roles. But neither film updates the language. The actors have clearly all gulped down their acting juice and try to communicate as much as they can through tone, and the stream of syllables coming out of their mouths sounds sort of like our language, but it just isn't. As a result, I was reminded of nothing so much as Karl Eccleston and Brian Fairbairn's short film Skwerl:

Some of those who have encountered my grumbling about Shakespeare have protested that I'm being silly and that his language is perfectly comprehensible. Yet it seems to me that there must be a reason that — with the exception of William Vollmann's novel Argall, which I also found opaque — the contemporary works I'm familiar with that are set in the Early Modern period do not themselves employ Early Modern dialogue. Oh, there might be a few archaisms thrown in for flavor, but for the most part they steer clear of the full "dull and muddy-mettled rascal, peak, like John-a-dreams, unpregnant of my cause" routine. That sort of language might make sense on the page — eventually, with careful attention — but not when rattled off in real time. So better to go with somewhat inauthentic but comprehensible language if you want to impress people with your story rather than with the trimmings you've added to a 400-year-old cultural fetish object.

|

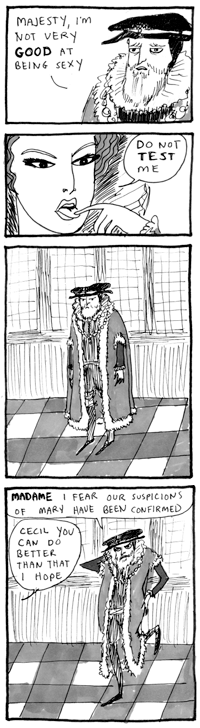

Michael Hirst, 2007-2010

For example! I went into this under the impression that it was basically a generic soap opera with some 16th-century names sprinkled in. And it's true that things have been sexed up: Henry VIII remains a strapping young pretty boy well past the point when, in real life, he had ballooned up to 400 pounds, and we're treated to a fair amount of nudity by some of the comelier queens. But as the series wore on, I grew steadily more impressed. This isn't Henry VIII as standard-issue Romance Novel Guy; on the contrary, The Tudors does a worthy job painting a portrait of Henry as a Renaissance Stalin, a paranoid autocrat conducting bloody purges of the highest levels of government on a regular basis. The series does take liberties with history, but on the whole it's surprisingly faithful — many times I went to Wikipedia to learn more about the real-life underpinnings of an episode, only to discover that the episode had followed reality (or at least some anonymous contributor's version of it) very closely. And I also have to give The Tudors a thumbs-up as narrative. There were some really powerful sequences: Henry's last meeting with Charles Brandon, for instance, or Catherine Howard dancing in the tower… in fact, Catherine Howard, as written by Hirst and played by Tamzin Merchant, quickly became one of my favorite TV characters, and her arc made the Marie Antoinette movie look that much worse by comparison. So, yeah, when those TV recommendation engines said that based on my input it seemed like The Tudors would be a good match for me, apparently my disbelief was unfounded.