Margaret Leech, 1959

There are at least a couple of series out there offering short biographies of every president, even the obscure ones — that's how I found a book about Benjamin Harrison, for instance. But when I was looking for a book on William McKinley, I discovered that in addition to the President-of-the-Month-Club selections, there was a McKinley biography that had won both the Pulitzer and the Bancroft Prize, so even though it was from 1959 I decided to read that one. Whoops. It's pretty bad. It's basically 600 pages of minutiae — which colonel was on which island on which day, who was sitting where at the inauguration — that adds up to not much of anything. I learned little about McKinley or the themes of his presidency. One thing I did learn, however, is that the word "dude" meant something different in 1959 than it does today. Apparently it meant "dandy" or "fop," and it's one of Leech's favorite words. Theodore Roosevelt was an "eyeglassed dude," Addison Porter was a "minor Republican dude," etc. I also learned that the 8th Ohio Volunteer Infantry was led by Col. Hard and Lt. Col. Dick. So there's that.

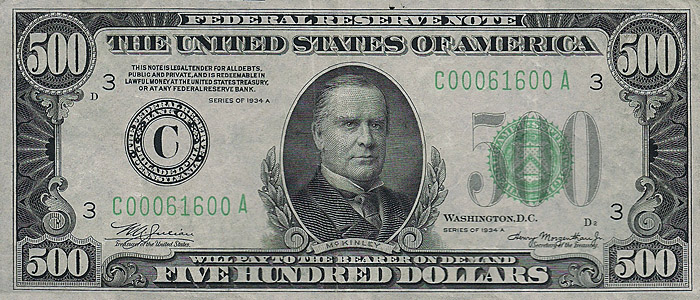

1896 found the economy struggling. It had been in an acute downturn since 1893, but the economy had been in generally poor health since the 1870s. William Jennings Bryan, whom I suspect would be much more interesting to read about than McKinley, won the Democratic nomination on a populist platform, arguing that the remedy was aggressive inflation to ease farmers' debts. This program would have correspondingly devalued the holdings of the wealthy. Ohio governor William McKinley was not himself exceptionally wealthy, but he was of the opinion that whatever was best for big business was probably best for America. During his time in Congress he'd specialized in putting together high tariff packages, driving up the prices of imports so that owners of domestic businesses could keep their own prices high enough to pocket handsome profits. They rewarded McKinley by flooding his campaign with cash — a sum equivalent to $3 billion today. While Bryan criss-crossed the country giving rousing speeches, becoming the only the second presidential candidate to campaign on his own behalf, the railroad tycoons slashed the fares to McKinley's hometown of Canton in order to encourage reporters to go to his house and listen to his counterarguments. One put forth by McKinley and his surrogates was that those employed by business should support policies that aimed to make businesses prosperous, for prosperous businesses could afford to pay their workers enough to build little nest eggs of their own — nest eggs which Bryan proposed to make worthless. This argument ended up winning the day; urban workers, freaked out that a Bryan win would wipe out their small savings, ended up voting Republican by a 3-to-2 margin.

McKinley was thus elected as basically a caretaker president, a guardian of the status quo. To his surprise and chagrin, he ended up as a war president. Spain had recently taken a harder line against the Cuban independence movement, and tales of atrocities filled the U.S. papers. Public sentiment was in favor of intervention. It had been less than two generations since the Pierce administration had fumbled an attempt to seize Cuba from Spain; it had also been less than two generations since anti-Catholicism had been a strong enough force in American politics to serve as the rallying point for a major political party, and Americans generally thought of Spanish colonialism in the execrating terms that would come to be known as la leyenda negra. Delivering the coup de grâce to the Spanish Empire struck many as a splendid way for the U.S. to announce itself as a world power. When the battleship Maine, in port outside Havana to keep an eye on things, blew up under circumstances that remain mysterious, the drumbeats for war grew deafening. Among the rare voices of skepticism were many business leaders, who put a premium on stability. Perhaps not coincidentally, for a good while after a bipartisan majority of Congress had determined that war was the only answer, McKinley continued to hold out for peace; Roosevelt, then assistant secretary of the Navy, grumbled that McKinley had "no more backbone than a chocolate éclair." Efforts to negotiate a peace were hindered by the fact that McKinley had chosen his cabinet largely out of political motives, and to honor senior members of the Republican Party. For Secretary of State, McKinley had appointed the senile John Sherman, freeing up Sherman's Senate seat for McKinley's close advisor Mark Hanna; Sherman had embarrassing lapses of memory during his meetings with European diplomats and McKinley eventually had to ask for his resignation. Ultimately, McKinley gave up his attempts to head off a war, and hostilities commenced.

The Spanish-American War was pretty short as these things go. The U.S. Navy wiped out its Spanish counterpart both in the Caribbean and in the Pacific, and after four months of fighting losing battles, the Spanish agreed to sell Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam to the United States for $20 million (about $20 billion today). This isn't to say that everything went smoothly. The U.S. military proved incompetent at logistics, and even loading troops onto transports tended to be a fiasco: the soldiers would get on the ships, sit there sweltering and starving for a day and a half, and then be ordered to disembark without the ships ever having left Tampa. Disease was rampant. When the public heard about the red, slimy, unsalted canned beef the soldiers had been forced to choke down, war secretary Russell Alger became a reviled figure and was eventually forced to resign. Meanwhile, McKinley and his advisors weren't sure what to do about the Philippines. McKinley hadn't even been able to find the Philippines on a map when he'd first had to appoint a representative in Manila. Now he had to decide the fate of a country of seven million. The resolution giving him the authority to invade Cuba had been accompanied by an amendment specifying that the United States would not annex the island; the New York Times grumbled that knight-errantry was no better reason to go to war than a land grab would have been, but the amendment brought a number of wavering congressmen into the war party. No such amendment tied the president's hands where the Philippines were concerned, and McKinley eventually decided that to keep the archipelago from being sold to Germany, the U.S. had better adopt a policy of total annexation. It turned out that the Filipino insurgents were no more pleased to be living under the American flag than under the Spanish one, and the Philippine-American War that began as a result ended up outlasting McKinley, who won a rematch with Bryan but shortly thereafter became one of the many world leaders in this period to be assassinated by an anarchist.

So what kind of guy was McKinley? He seems to have been a nice enough sort. He was devoted to his clingy, demanding wife who had become an invalid in her 20s, and when he got shot, his first words were "Don't let them hurt him" — that is, don't let the mob hurt the man who had just ended his life. As noted, he genuinely believed that the country as a whole would benefit from policies that happened to especially benefit the rich and powerful, winning him rich and powerful allies; these allies took care of whatever deal-cutting or other skullduggery was required to pave his way to high office, leaving McKinley free to muse earnestly about what was "right and fair and just." When it came time to make big decisions, he told reporters that "I am not ashamed to tell you, gentlemen, that I went down on my knees and prayed Almighty God for light and guidance," and that where the Philippines were concerned, it came to him "that there was nothing left for us to do but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them, and by God's grace do the very best we could by them, as our fellow-men for whom Christ also died." Which raises the question: Who cares? If you're a Filipino circa 1899, do you care whether the Americans have taken over your country to "uplift" you or whether they just want to get rich off the coconut plantations? If you're a farmer drowning in debt, do you care whether the economic policies crushing you were motivated by greed or whether they were based on the earnest theories of the college dropout in the White House? And I guess the answer is that voters care. Tell them, as Bryan did, that certain policies are destroying lives, and the natural response of a lot of people is to say, "That's horrible! What dastardly villain is behind all this?" And then, if instead of a sneering robber baron in a top hat, they see a decent feller who says he's prayed over it and these policies strike him as right and fair and just, they're likely to conclude that the policies can't be as bad as all that.