Antonio Skármeta, Pedro Peirano, and Pablo Larraín, 2012

#21, 2013 Skandies

My first three years of high school I was an active member of the speech and debate team, but my freshman year I mostly did Student Congress, and my junior year I did nothing but individual events. My sophomore year, 1987-1988, was my one year doing Oxford debate, and the resolution that year was "that the United States government should adopt a policy to increase political stability in Latin America". I knew virtually nothing about Latin America before I started cutting up prep books and pasting quotes onto cards, and to be honest, I still knew virtually nothing a year later. I can't speak for my teammate, but I tended to approach a debate like a Magic: the Gathering game: listen to the opponent's speech, note down the attacks, frantically search our files for cards to fend off those attacks. Actually learning about Latin America and understanding the political situation in each country was not on the agenda. To a great extent, the Latin American leaders I could identify in the summer of 1988 — Fidel Castro, Daniel Ortega, possibly Manuel Noriega — were the same ones I could identify in the summer of 1987. The lone exception was the military dictator of Chile, Augusto Pinochet. Him I learned about. Rarely did a tournament go by without our running into multiple teams who focused on the question about what to do about this U.S.-backed human rights nightmare. In the spring of 1988, though, I assumed these debates were entirely theoretical. Pinochet had been in power since before I was born. I couldn't imagine that he was actually going anywhere. The idea that he might actually be toppled before the year was out never even crossed my mind. And yet that's what happened. No is the story of how Pinochet got the boot.

First, some background. In 1973, the Chilean military, backed by Richard Nixon's CIA, overthrew Chile's democratically elected socialist president, Salvador Allende, and top general Augusto Pinochet declared himself "supreme chief of the nation". The junta suspended Chile's constitution and took its time composing a new one, which was finally ratified in 1980 in a fraudulent referendum. It called for the president (Pinochet having adopted that title by this point) to go before the voters every eight years, not in a contest against another candidate, but in a simple "yes" or "no" vote — because if opposing candidates were allowed to run, they might cry foul after Pinochet made up some numbers and claimed victory. But a lot can change in eight years. By 1988, the era of glasnost and perestroika had arrived, and in the face of friendly overtures from Moscow, the United States could not be seen to support a transparently rigged election by a military dictator. With America hedging its bets, and even the Roman Catholic Church putting pressure on the Chilean regime, Pinochet's people reluctantly agreed to allow the No campaign fifteen minutes of TV time per night to broadcast its message. The Sí campaign also received fifteen minutes, which was sort of academic given that the state also controlled the other 23½ hours of airtime each day.

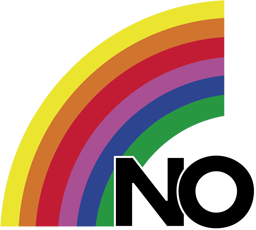

The Sí campaign had another advantage: it got to call itself the Yes side, with all the positivity that implies. You can probably guess what the Sí ads looked like: cheering citizens; singing children; a beaming, grandfatherly Augusto. And, initially, the No campaign played right into the Sí campaign's hands. The early drafts of its TV spots were full of footage of dead bodies, citizens being beaten, troops giving Nazi salutes as they marched down Chilean streets, a scowling Pinochet, and red captions blaring horrible statistics: 34,690 tortured, 200,000 exiled, 2110 executed, 1248 disappeared, each accompanied by the plea, NO. The higher-ups in the No campaign thought they'd put together something very powerful. Enter the advertising industry, whose avatar in No is René Saavedra, a composite of several real-life figures. Saavedra asks whether the No managers are actually trying to win. They talk around the question but eventually concede that, no, they are realists, and know that they can't win a rigged election; what they can do is take advantage of their fifteen nightly minutes to give Pinochet the fiercest kicking they can. Saavedra calls for a retool based on the notion that in politics, the more optimistic campaign always wins. Ignore the fact that the good guys have been saddled with the word "No". That's just the name of the product; it might as well be "Pepsi". It's not the brand. The brand is… and here he and his team go off to brainstorm, trying to think of something that cannot be outflanked. What they come up with is alegria — "joy". Joy is the brand. The logo will be a pretty rainbow, and while it'll have to be accompanied by the word NO, they will boldly ignore the incongruity. And yes, they'll spend a few minutes each night talking about Pinochet, the way an ad for McDonald's generally has to show the food, briefly, reluctantly. But most of each broadcast will be straight out of the cheesiest '80s commercial you can imagine — a goofy guy dancing alone to a Walkman, laughing people riding horses through the countryside, little kiddies jumping on their parents' bed, dancers in bright colors, mimes for some reason — all of it accompanied by a catchy jingle: "Chile, joy is coming! Chile, joy is coming!" Some of the original No campaign higher-ups are outraged. Augusto Pinochet is a mass murderer, they point out. His government has tortured enough people to fill a stadium. This isn't an abstraction. Pinochet killed my brother, one snarls. And after the election is over, the same will probably happen to all of us, for daring to oppose the dictator. So if we're going to put our lives on the line, shouldn't it be for something? Rather than an empty-headed campaign that says nothing?

This is the conflict in a nutshell. Saavedra claims that his campaign full of rainbows and inane comedy bits is the most serious possible approach, because it is engineered to bring about tangible change. Empty-headed optimism is what wins. So will you bottle up your feelings for the time being so we can actually kick Pinochet out of office? Or would you rather give up that chance in order to vent your righteous fury?

And it becomes clear that, in fact, for many people in the No campaign, emotional release is indeed more important than victory.

But not enough of them to derail the new direction. The No campaign did in fact go with the "joy is coming" approach. Its internal polls indicated that support was going up — not by convincing Sí voters to switch to No, but by convincing people who hated politics to participate anyway. On election night, the state-run media dutifully reported the fake numbers Pinochet's people supplied, but again, Pinochet had been forced to hold a fair vote, which meant that outside observers were able to make a parallel count. So while Sí cruised to victory on TV, the real numbers spread by word of mouth: No 56%, Sí 44%. And when the generals heard those numbers, they went to the presidential palace to tell Pinochet that if he wanted to continue with the charade, he was on his own. Pinochet capitulated. A presidential election was held the following year, and Pinochet stepped down upon the inauguration of Patricio Alywin in 1990.

By that point I had switched from the debate team to the Oracle, our school newspaper. A while back I was going through some old VHS tapes (as opposed to some brand new VHS tapes, I guess?) and happened across a video of the 1990 Oracle banquet, shot on an '80s camcorder. I mention this because No was also shot on an '80s camcorder, to give it just that extra touch of period flavor. Every object on screen is surrounded by multicolored haloes, and every time the camera happens upon a light source the screen is swallowed up in white. So while I found No very interesting as a piece of history, if it's crisp cinematography you're looking for, the title correctly assesses whether you'll find it here.