George Stone, Rocky Morton, and Annabel Jankel, 1987

To kick off 2017, let us travel twenty minutes into the future… and thirty years into the past.

Max Headroom, the character, was created in response to MTV, which had debuted on 1981.0801 to immediate, massive success. Music videos had been around for a while — apparently the Beatles made forty-six of them between 1963 and 1970 — but MTV’s innovation was to create a televised radio station out of them, not only playing videos around the clock but interspersing them with segments in which “VJs” would introduce the clips, do promotions, share tidbits of music news, interview artists, and in general serve as the faces of the channel. Other media outfits scrambled to copy MTV’s format. NBC, for instance, whipped together a show called Friday Night Videos, with celebrities such as Hulk Hogan and Dr. Ruth Westheimer serving as hosts. Out in Britain, the fledgling Channel 4 couldn’t afford that kind of star power, so when its execs teamed up with Chrysalis Records to launch a music video show and needed some kind of bridging material between clips, they hired the people who had done the Friday Night Videos title sequence and asked for “some kind of graphics”. One member of that team, Rocky Morton, grumbled that after the latest Duran Duran or Michael Jackson extravaganza, some little cartoon banged out on a Channel 4 budget would be boring — and then he had a stroke of inspiration. MTV had put forward a diverse lineup of VJs chosen for their ability to connect with the youth of the ’80s. What if Channel 4’s show also had a VJ, but it was a boring, middle-aged whitebread guy? That would be hilarious! And throw in one more twist: so the execs wanted “graphics” instead of a VJ? Make the VJ a computer-generated boring, middle-aged whitebread guy! Of course, at the time computer graphics couldn’t generate a human face much more sophisticated than Evil Otto, so the team quickly settled on a plan to stick an actor in some latex makeup and tell people that it was all done with computer graphics. Writer George Stone dubbed the character “Max Headroom” very early on, but it wasn’t until fairly late in the development process that Morton hit upon one further conceit. Precisely because generating a human image, even if only from the shoulders up and only to uncanny valley standards, was so far beyond the capabilities of the day’s computers, he started playing around with video loops to suggest a processor struggling to keep up: dropping frames, chipmunking Max’s voice, and the gimmick that would define Ma-Ma-Max Headroom above all else, the stu-stu-stuttering. the stuttering. The Max Headroom Show debuted on 1985.0406 and quickly became a big hit for Channel 4 — at the beginning of the first season Max was introducing videos by obscure German techno bands, and by the end of it he was interviewing Sting. But that’s not the show this article is about.

When Stone heard Morton’s concept, he thought that five minutes of each show should be set aside for some narrative content, so that as the weeks went on, the audience would get a clearer picture of how this computer-generated TV host came to be. He and Morton came up with a season’s worth of material, but while the higher-ups at Channel 4 liked their story, they weren’t willing to sacrifice a music video every week for it. Instead, they offered to air a TV movie laying out Max Headroom’s origin, with one catch: they wouldn’t pay for it. The creative team would have to find its own funding. Enter HBO, which was looking for unusual original programming for its subsidiary Cinemax.

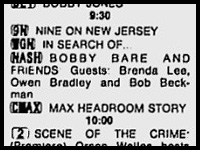

|

| Daytona Beach Morning Journal, 1985.0414 |

The same month that Max Headroom first appeared on British television, Coca-Cola changed the formula of its flagship soda to more closely resemble Pepsi, which had been gaining market share. Though sales of New Coke were good, a backlash erupted in the South, and Coca-Cola found itself inundated with calls and letters condemning the company for its assault on a beloved Dixie institution. In less than three months it backtracked and announced the release of a corn syrup based version of the old formula under the name “Coca-Cola Classic” — and this time not only was the customer feedback ecstatic, but sales skyrocketed. Problem solved, right? Well, not entirely. When New Coke was initially rolled out, the ad campaign pretty much wrote itself: just hire a beloved big-name celebrity to attest that New Coke is better than the old stuff — and when it comes to drinks, if you can’t trust Bill Cosby, who can you trust? — and your job is done. But now the task at hand was to find a way to sell New Coke alongside Coca-Cola Classic — to revive its now plummeting sales without in any way impugning its apparently sacred predecessor. The ad exec McCann Erickson hired to take over the Coca-Cola account was a guy named Arnie Blum, and the angle he took was to divide up the customer base generationally. If the old Coke was now “classic”, then the new one could be billed as the opposite of classic: hip, edgy, modern, something your parents might scoff at but that you and your friends are cool enough to get. Now the question was where to find an appropriately hip, edgy, modern pitchman. And it just so happened that before coming to McCann, Blum had worked at BBDO, and someone at BBDO’s London office had sent him a tape of The Max Headroom Show. The Max Headroom “Catch the Wave” New Coke ads went up in April of 1986, and within a month, 76% of American teenagers could recognize and name the character. Good news for Coca-Cola, but even better news for Cinemax, who suddenly had a big star on its Friday night lineup, and the best news of all for Chrysalis, which owned the rights to the character and could unleash a torrent of tie-in merchandise. It could also try to strike a TV deal with a network with more viewers than Cinemax.

ABC was languishing at third place in the ratings and therefore more willing than NBC or CBS to experiment with something different from the usual network TV fare. Stu Bloomberg, ABC’s head of development, had happened to be in London on 1985.0404, had seen the Max Headroom TV movie on Channel 4, and had been so taken by it that the moment it ended he put in some calls and scheduled a meeting the next morning with the creative team. So when Peter Wagg from Chrysalis shopped around a Max Headroom series, not only did ABC make him the best offer, but he knew that his contact there had been keen on the concept long before the character made the cover of Newsweek. Of course, being keen on the concept didn’t necessarily mean being keen on its conceivers. George Stone had been off the project since before the character ever went on the air: his script for the TV movie was full of “people shooting at each other with laser guns and deflecting the lasers with hubcaps”, and Wagg ended up hiring another writer. Rocky Morton and Annabel Jankel directed the TV movie, but were not invited to participate in the ABC series, and soon found that they couldn’t afford the legal fees required to assert ownership of the character. But, surprisingly, the ABC show was not a huge departure from the work of the original creators. Stone’s notes ended up serving as the ABC show’s bible, and the pilot episode was a reasonably faithful remake of the Channel 4 movie and even retained a couple of the British actors. And with all that history out of the way, I think I can finally talk about the show itself.

As I alluded to up top, Max Headroom bills itself as taking place, in one of my all time favorite phrases, “twenty minutes into the future”. Society revolves entirely around television. Politicians still exist, but each network sponsors its own candidate, and elections are won by the candidate whose network has the highest ratings at the designated time. The criminal justice system still exists, but courtroom trials have been replaced by game shows. The shows that we catch snippets of make prolefeed look like high art: they’re just montages of dogs walking around, or loops of a guy shooting a rocket launcher at an unspecified target, repeated for an hour. By far the best thing about Max Headroom, though, is not what it does with television — it’s not the world’s most incisive satire — but what it does with televisions. They’re everywhere. In fine dining restaurants, TVs sit beside every table. When a top executive goes swimming in his palatial indoor pool, a TV set floats along beside him. A couple has a romantic moment in front of a crackling fire, and after a moment we notice that it’s actually a video of a fire playing on a TV that’s sitting in the fireplace. Even out in the burnt-out wasteland surrounding the city, the filthy rag-clad masses huddle around stacks of battered television sets as they gnaw on their roasted rats. The fact that in 2017 boxy analog TVs are obsolete only reinforces the aesthetic of the show: though the shots of dark skyscrapers silhouetted against a hazy night sky call Blade Runner to mind, an even stronger influence is Brazil. The world of Max Headroom is both shockingly high-tech — artificial intelligence now passes the Turing test — and shockingly low-tech: the fact that all the computer graphics look like they were generated on a 5¼-inch floppy version of AutoCAD is probably all the production team could manage at the time, but even in 1987, computer keyboards didn’t look like grotty 19th-century typewriters they way they do on this show. The production values reflect this dichotomy. Here’s a show that shares its prime-time block with three-camera sitcoms like Who’s the Boss? and Growing Pains, and it’s a sci-fi noir thing that looks like nothing else on the TV of the time. Yet at the same time, to a modern eye, it looks seriously amateurish, like it was shot on a VHS camcorder.

The premise of Max Headroom is that, in order to access the memories of comatose investigative reporter Edison Carter, teenage computer prodigy Bryce Lynch uploads Carter’s mind into the computer system of their mutual employer, top-rated Network 23. The result is a glitchy computer-generated version of Carter whose first words are “Max Headroom” — part of the sign on the barricade Carter smashed into that left him comatose in the first place. Living in its computer system as he does, Max can interrupt Network 23’s programming at will, which annoys the top brass, but since he gets huge ratings when he does so, they let it slide. The problem for those of us in the real world, watching ABC rather than Network 23, is that Max’s appearances consist of:

- the stuttering thing

- silly voices

- wacky Jim Carrey faces, though we didn’t call them “Jim Carrey faces” back when Jim Carrey was just the Once Bitten guy

What they do not generally consist of is funny jokes. To be fair, that may be at least partially deliberate, since the character is not necessarily supposed to be a laugh riot but rather a preening, empty-headed TV host. Still, this tedious schtick would basically be death if Max were the main character rather than merely the title character. As it turns out, though, he’s barely in the show! I remember my classmate Bob Mathews complaining about this back when the show was on the air: “It’s an hour of all these other characters and then Max shows up for five seconds and says ‘Wow!’”. And, yeah, that’s about the size of it. There are a handful of plotlines that hinge on Max’s status as the world’s most popular TV personality. There are also a handful of occasions when the other characters need Max’s help to get into a computer system or something. But for the most part the series consists of Edison Carter uncovering scandals in his dystopian world while Max Headroom doesn’t actually do a whole lot. Max’s usual role is to pop in a couple of times per episode and provide five seconds of… well, five seconds of Mork, really. Like Mork, he does some sort of ostensibly humorous riff from a naive “What is this Earth thing you call ‘kissing’” perspective, with a big dash of moralism thrown in. The difference is that Mork was played by Robin Williams, and Max Headroom was played by Matt Frewer. And even Robin Williams’s improvisational hurricanes never did much for me — comedically, they seemed to me to contain a lot of heat but not a lot of light. So the off-brand Matt Frewer version is just that much worse.

So what about that vast majority of Max Headroom that does not actually involve Max Headroom? It’s not actually a good show — I wouldn’t recommend it as art or even as entertainment — but it at least merits the tag “interesting failure”. As a cultural document, it’s fascinating: cynical enough to put forth a plotline in which networks sign deals with terrorist groups to commission and land exclusive coverage of explosive attacks during sweeps week, and yet naive enough to think that those networks would have qualms about a casualty or two. Some of this undoubtedly reflects the tug of war between the creative team and ABC, which got pretty meta toward the end of the show’s run:

- each week the creative team, whose chief aim was to satirize network television, would try to get away with as much as possible without getting the show canceled

- ABC in turn would respond by figuring out how much to let through, given that it wanted to attract a cynical Gen X audience, but could only countenance so much mockery

- the creative team then gave the audience a peek behind the curtain at this very dynamic and the corporate reasoning behind it, using Max Headroom’s “trashing” of Network 23 and its chief sponsor, the Zik Zak corporation, as a metaphor for Max Headroom’s tweaking of ABC and its sponsors; explains one Network 23 executive, “Research shows that Max Headroom speaks for the young and dissatisfied. He says what they feel. The fact that Zik Zak allows Max to mock their commercials allows this audience to identify with Zik Zak.”

And yet I can’t ascribe the show’s naivete entirely to network bowdlerization, because it was the original creative team that was naive enough to make the show revolve around a successful investigative reporter. Almost every episode adheres to the same formula:

- someone launches a nefarious scheme, like TV commercials that are very effective but make some viewers explode, or a channel that broadcasts people’s dreams but kills some of the dreamers, or a TV show that gets huge ratings through subliminal neurological hacking

- Edison Carter valiantly exposes the truth

- the public actually cares and the evildoers are ruined

This plays like an artifact from not just another time but practically another planet in the aftermath of a political campaign in which investigative reporters uncovered scandal after scandal involving one of Max Headroom’s fellow relics of the 1980s — his compromising ties to a hostile foreign power, his fraudulent “university” that swindled tens of millions of dollars from poor people, his boasts of committing sexual assault with impunity — and not only did these exposés not ruin him, but they didn’t even serve as an obstacle to this preening, empty-headed TV host getting elected president of the United States. And that was far from the only data point in recent years to suggest that, on the whole, people don’t really care about the kind of malfeasance Edison Carter brings to light. In one early episode of Max Headroom, Carter reveals that a popular new sport is fatal for some of the participants; on the show, the sport is immediately shut down, while in the real world, the NFL continues to bring in eleven figures a year. In Max Headroom, meddling with the credit system is considered worse than murder; in the real world, the wolves of Wall Street precipitated a credit crisis that triggered the worst economic collapse in eighty years, but none of the criminality that was uncovered put anyone in jail, and there was no public outcry of any consequence. So, yeah — at the moment, at least, the idea that Edison Carter’s reports wouldn’t fall on deaf ears seems so hopelessly utopian to me that it might as well be a fantasy triggered by one of Zik Zak’s Neurostim bracelets.

To close, some Max Headroom minutiae:

- One of the things that most struck me when this show was actually on

the air was that the TV screens in it were so cluttered.

These fictional TV networks stuck big logos in the corner of the

screen!

And had chyrons running nonstop along the bottom!

There was barely any space for the picture!

Talk about a dystopian future!

Then came 1993, and the dystopian future was

upon us.

Decades later, every time I see the CBS eye or the NBC peacock in the

corner of a TV screen I can’t help but think about how Max

Headroom did it first.

- Shows from The Brady Bunch to Buffy the Vampire

Slayer have revamped their opening theme music midway through

their runs, but I don’t know of a more massive upgrade than the one

Max Headroom’s opening underwent between its first

and second season, thanks to new music by Michael Hoenig.

Check it out:

Season 1 Season 2 - In one episode, Bryce uses his elite computerin’ skillz to

take an old movie and replace the Trojan horse with a sheep.

In 1987 I thought this was an eye-popping

special effect and the sort of thing that wouldn’t be possible

on a home computer in my lifetime.

Nowadays that sheep looks crudely superimposed.

A child could do a better job with Avidemux and it would only take a

few minutes.

(This is the same episode in which our heroes save the day by splicing

the word “not” out of a politician’s statement before

putting it on the air.)

- Though I didn’t generally find Max Headroom particularly funny, I did like some of the little throwaway jokes the writers slipped in here and there, like the reference to a Southwestern city called “San Menudo”. There’s an even better city name hidden in a text readout in another episode. Again, this show aired in 1987, juuust late enough that writers were beginning to imagine that the Cold War might not last for millennia. In a very ’80s move, the sole superpower in Max Headroom is Japan. So what happened to the USA and the USSR? We get a hint when we see that city name: “Reagangrad”. And hey, now that the GOP is functionally a subsidiary of the United Russia Party, who knows — that one might yet prove as prescient as the network bugs!