C.J. Cherryh, 1988

the thirty‐third book in the visitor

recommendation series;

suggested by Lucian Smith

I was originally going to start off this article by saying, “To my surprise, not about a teenager in cyberspace!”, but then I discovered that Lucian’s review starts almost exactly the same way: “So, I read ‘Cyteen’ which turned out to not be about a cybernetic teenager. Bonus!” Great minds think alike, I guess. Which is actually what Cyteen is about! That is, it’s about a world that is experimenting with cloning geniuses, with spotty results: the clone of the greatest scientist of the 23rd century becomes not the greatest scientist of the 24th century but rather a failed musician. The natural clones known as identical twins may indeed tend to have roughly the same raw brainpower, but they often turn out to lead very different lives—and that’s growing up in the same household. How much more different might an artificial clone turn out to be, growing up not only in a different household but a different era?

Lucian mentions that the book has a few false starts, and while my Pattern 8 says that I tend to like structural tricks, the false starts are better to have experienced than to be experiencing—in retrospect, I recognize that they establish a lot of critical stuff, but they’re a chore to get through. The political wrangling at the beginning is extremely dull, and only some unusual circumstances which I’ll talk about later kept me from pulling the plug very early on. Then suddenly there’s an action sequence. The setup for this is that there are two categories of clones in Reseune, the city where most of the book is set: standard clones called “personal replicates”, and specially programmed clones called “azi” who serve as companions to many of Reseune’s citizens, simultaneously filling the roles of bodyguard, butler, best friend, and sex partner. For instance, a gay scientist named Jordan Warrick has both an azi companion named Paul and a personal replicate of himself named Justin, now seventeen, whom they are raising as a son. When the ruthless chief administrator of Reseune, Ariane Emory, herself the leading scientist of the day, makes a move against the Warricks by issuing a seizure order for Justin’s azi companion Grant, Justin sends Grant on a daring wilderness escape. Will clones on the run be what this book is about? No. The escape doesn’t work out. Emory has Grant tortured, and personally drugs and rapes Justin, leaving him in the grip of post‐traumatic flashbacks. In the aftermath, it looks like this may be what sets the real story in motion, and that the rest will be about the Warricks’ recovery and revenge. Again, not so much! Abruptly, Emory is found murdered. But she has left behind plans that her allies quickly put into action. Not only is Emory to be cloned, but young Ari is to be raised in a manner that will as closely as possible approximate Emory’s own upbringing so that she will grow up to become a true duplicate and not a different woman who happens to have the same face. For instance, Emory’s mother died when Emory was seven; therefore, young Ari is to lose her mother figure when she is seven. And when she comes of age, young Ari will be given access to Base One, a computer system equipped with a Galatea‐style NPC version of Emory to guide her through the execution of Emory’s unfulfilled schemes. This, it turns out, is what the book is about. It’s a detailed account of a little girl growing up. Specifically, of a little girl being groomed to take on the mantle of the evil genius to whom she is genetically identical. But her upbringing can’t help but have differences from Emory’s—different guardians, different friends, a different era—and as the years add up, it remains an open question to what extent young Ari will grow up into another Ariane Emory and to what extent she will grow up to atone for the sins of the original. All of this is way, way more interesting than anything that came before. It is also, unfortunately, more interesting than anything that happens after young Ari does grow up and the book returns to the political wrangling that made the beginning such a slog. Apparently the latter carries a lot more import for those who have some investment in Cherryh’s “Alliance‐Union universe”, which consists of several dozen novels—it contributes to the world‐building for which Cherryh is so acclaimed. But I have no such investment. For me this book was all about the girl‐building.

The themes surrounding Ari II have resonance beyond the literal issues involved in human cloning. I often find myself thinking about the other versions of me I could have become had things gone a little differently. For instance, when I was six, my father finished his medical residency and announced that he was moving our family from the Mid‐Atlantic states, where I had spent my entire short life, to Michigan. Then there was a change of plans, and it was Georgia that we were off to; I spent weeks staying with my grandparents while my father looked for a house down there. And then came one last swerve, as suddenly we were off to California instead, and this time within a matter of days I was on a plane to LAX. It is weird to think of what a very different person Rust Belt Me or Southern Me would have been—raised in a different regional culture, educated by and among entirely different people, speaking with a different accent—and yet it actually would have been my consciousness having all these foreign experiences! Or maybe that’s not so weird, given how different I can remember my thinking being at different points in the life I actually have led. Human behavior is so wildly inconsistent and so contextually determined that to duplicate a person seems like looking into a kaleidoscope, liking the pattern you see, and trying to recreate it by building an identical kaleidoscope. Good luck! Yet even as I find myself tempted to argue that the self is nothing but an illusion, that over time I’ve dropped what I once thought were core parts of my identity and yet continue feel like “me”, I have to admit that I do keep falling into the same behavioral patterns even when I don’t want to. Epiphanies and vows to change my ways tend not to stick. As another for‐instance, I can’t count the number of times I have vowed to take active steps to build more of a social life, only to realize a few weeks later that it’s been three days since I talked to anyone or left my apartment. My understanding is that basic personality traits like introversion are fairly hardwired and probably would be duplicated in a cloning project like that in Cyteen. So maybe any version of myself that started with the same genetic material would have the same inclinations regardless of upbringing. Still, I don’t think that duplication of such vague traits counts for much. Maybe all my alternate selves also spend days at a time in their apartments, but instead of writing Calendar articles, one version of me is holed up in a home office drafting end‐user license agreements and another is sitting on the floor watching The Alex Jones Show while eating a bag of Doritos. (That one is probably the Michigan version, thanks to all the lead in the water supply.)

Now I have a confession to make. I didn’t actually read Cyteen. Last week I went to Oregon to watch the eclipse, and to fill the 30+ hours of the drive there and back, I listened to the audiobook version. (Those are the special circumstances I mentioned earlier: I stuck with Cyteen because it was the only entertainment I had with me!) I’d listened to non‐fiction audiobooks before, but this was my first audiobook novel. Though I have no real basis for comparison, it seemed pretty well done to me; I was impressed by the way that the narrator, an actress named Gabra Zackman, was able to come up with distinct voices for over a dozen characters, such that I could pretty much always tell who was talking without needing a “Justin said” or “Catlin said” tag. Yes, with over a dozen distinct voices some of them did turn out a little goofy, but a couple of the male voices were astonishingly convincing: Zackman did a spot‐on teenage boy and a froggy male nerd voice that genuinely made me forget that I was actually listening to a woman. However, I don’t think that audiobook novels are entirely for me. I tend to be a dweller—I read a few lines and muse about them—so the fact that the story kept right on going unless I actively paused it was a little irksome. The fact that there was no way to easily go back and skim for a plot point I had missed or a reference I didn’t get was even more so. But what may have been worst of all was that all of these characters and places were getting introduced and I didn’t know how their names were spelled! I actually pulled off the freeway and found a Starbucks so I could get on its wifi and look up how to spell “rez‐yoon” and “ah‐zee” and a bunch of other terms. I didn’t get them all: in researching this article I learned that the character whose name I had thought was Gerard was actually “Giraud”, and it was a minor personal crisis. (And yet it also drives me crazy to watch an English‐language movie or TV show with the captions on. See what I meant about inconsistencies?)

In a comment appended to his review, Lucian writes that Cyteen “is at least a great example for the dictum ‘Never judge a book by its cover’.” This made me wonder what the cover looked like, since I only had MP3 files on a USB drive. So I did a little poking around and discovered that Cyteen has borne a number of covers over the years. Here is some of the art those covers have used.

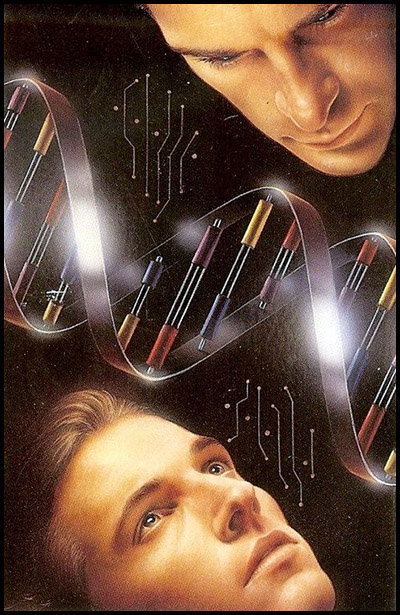

It looks like the current edition of Cyteen uses this image by Keith Birdsong:

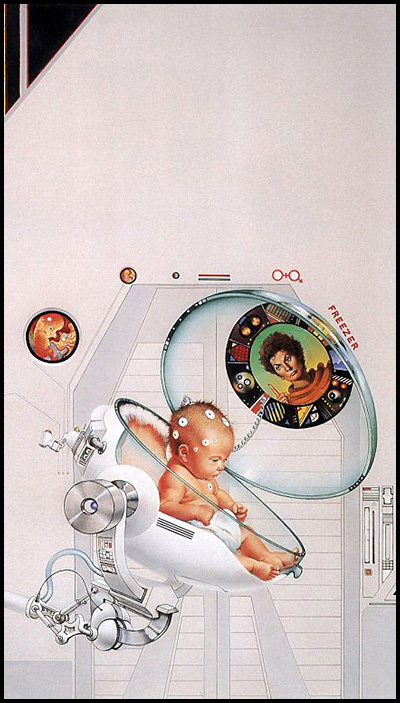

This suggests that the book you are about to read has something to do with genetics and electronics; what it does not suggest is that the book is about a girl. Interestingly, Cyteen was (much to the author’s chagrin) initially published in three volumes, and the Birdsong art might well make a good cover to the first volume, which revolves around the Warricks. Instead, the Birdsong art is attached to the complete edition, while the three‐volume edition bore the Don Maitz art below:

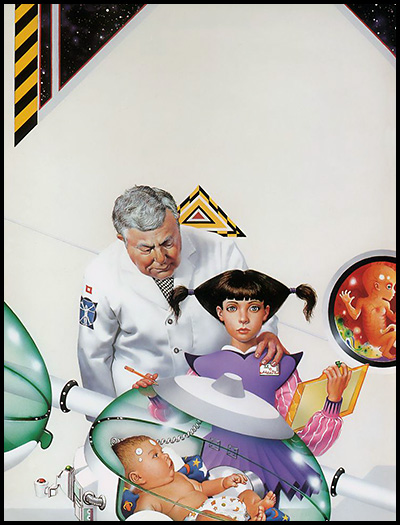

The above is about as straightforward a depiction of the plot as you could hope to find: we see the mind of the evil genius getting uploaded into the baby’s brain, which doesn’t happen exactly like that in the book but which gets the idea across. Volume two brings us Ari II as a little girl with a, um, futuristic hairstyle and pinafore:

And by volume three, Ari is all growed up again:

Ari II doesn’t actually grow to adulthood in a tube, but one edition nevertheless boasted this image by an artist whose name I wasn’t able to find:

Symbolizing death and rebirth in a less literal sense is this piece by Oscar Chichoni, an art designer on Douglas Adams’s ill‐fated Starship Titanic:

And finally, we have the publisher who looked at the Chichoni art and said, “I like the boobs, but can we do a version without the robot pissing on them? Oh, and more ass!”, and commissioned this cover art by Jan Patrik Krasny:

I have to assume that whoever decided to read Cyteen based on that cover wound up feeling disappointed.