Persepolis

Marjane Satrapi, 2000

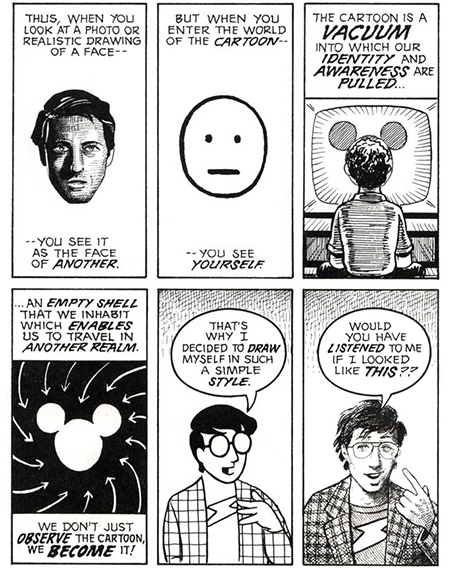

I read (and taught) this for four reasons. One was that I was teaching two sections of a class called “World Literature”, but the primary text of the first semester had been by a German guy, the primary text of the third quarter had been by a British guy, and the primary text slated for the fourth quarter was by another British guy. I really, really wanted to find a space in the schedule to bring in a female voice, preferably from outside Europe. Another reason was that Persepolis has recently become part of the high school canon—most of my tutoring students have reported having been assigned it, often in ninth grade—so I thought I should familiarize myself with it. A third reason was that there would be thematic continuity in moving from Animal Farm (about the Russian Revolution) to Persepolis (about the Iranian Revolution). And then a final selling point was that it’s a graphic novel and would therefore give me a chance to teach Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics. I saw that Persepolis was drawn in an extremely simple style, so I went straight to the bit in Understanding Comics about the power of the cartoon:

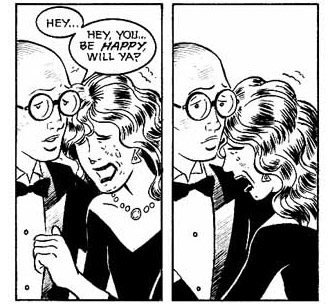

We talked about how Iran has been a recurring target of America’s Two Minutes Hate for forty years now and about how a big part of Satrapi’s project was to get Westerners to project themselves into Iranian characters rather than seeing them as The Other, and about how using such a simple style assisted in that effort. But… I didn’t entirely buy that line myself. I get the theory—I’d seen in Zot! how McCloud himself used a stripped-down art style to allow his group of misfit nerds to stand in for all the misfit nerds out there reading the book, and to make a picture of a girl bawling her eyes out look less like a picture of a specific girl bawling her eyes out than like a picture of misery itself. But there’s a difference between this:

and this:

That upper image, from Zot!, may look like the anguish depicted has been reduced to a blueprint, but the lower one, from Persepolis, is little more than an emoji. We can see how it is inspired by actual crying, but no one can cry individual pointy tears the size of quail eggs and no one can turn her mouth into a zigzag. It’s a collection of icons rather than a face. This let me talk about chapter two of Understanding Comics but not much beyond that. So I wound up using this as a pivot:

…and, casting Persepolis as an example of a comic from category one, I told my classes that we would wrap up our unit with a comic from category two. And that is a big part of why I gave up the flexibility of being a full‑time test prep tutor and took on a job at a high school. I miss being able to sleep in, but the SAT syllabus doesn’t allow me to spend two weeks leading class discussions about Zot!.

Hamlet

William Shakespeare and Kenneth Branagh, 1996

The second British guy I mentioned above was William Shakespeare. Regular readers will recall that every time Shakespeare comes up I grumble that while his plays might be rewarding to study, sitting down and watching a play in Early Modern English is the equivalent of watching a two-hour version of “Skwerl”. In the case of Kenneth Branagh’s Hamlet, make that four hours, as Hamlet is Shakespeare’s longest play and Branagh’s production is the only unabridged film version. And while in a temporal medium like film you can’t make the language more comprehensible by carefully poring over it word by word, it turns out that watching the movie multiple times, scene by scene, over the course of six weeks, has much the same effect. These were the third and fourth times I’d seen this movie and I got a lot more out of it by the fourth time around—I knew the script nearly by heart at this point and could focus on how Branagh tackles the problem of how to stage a 400‑year‑old play so that it’s interesting to a lay viewer (including the scenes every other production skips) without resorting to gimmicks like having MTV supply the soundtrack or having Hamlet deliver the “to be or not to be” speech in a Blockbuster Video. That was enjoyable enough that while I still can’t recommend that anyone just sit down and watch this for fun, I do recommend it to anyone who wants to study the play. I showed clips from five different film versions in my class and this one was the best by a wide margin.

Dead Again

Scott Frank and Kenneth Branagh, 1991

Speaking of Branagh, not everything I read and watched over the past sixty weeks was for school. I forget how his second movie, Dead Again, came up in conversation, but it seemed like a good excuse to revisit it—I’d liked it in college but hadn’t seen it since. The movie’s about a private investigator who attempts to find the identity of the amnesiac woman staying at his apartment, only to learn that her case may have something to do with that of a classical composer in the 1940s who was executed for murdering his wife, despite his protestations of innocence. A hypnotherapist suggests that the detective and his mind‑wiped love interest may be the reincarnations of the long‑dead couple, a hypothesis supported by the fact they are played by the same actors. The big twist, which floored me when I first saw it, is that [click to reveal spoiler]. What surprised me this time around is that (a) this twist is revealed a lot earlier than I had remembered and (b) it doesn’t actually end up mattering all that much. Too bad, because if the reveal had been better placed and if defeating the villain had depended on him misreading the situation along with the audience, this could’ve been a classic.

A Short History of Nearly Everything

Bill Bryson, 2003

In 2013 I audited a class on “big history”, a co‑production of the astronomy and integrative biology departments, that started with the Big Bang and steadily worked its way forward to the development of modern humans. A Short History of Nearly Everything was the textbook, so I figured that it’d be pretty much the same sort of thing. But it’s not, really! The idea behind this book is that here you have a layperson who has read the latest book written for a popular audience in basically every branch of science and will now summarize them for you so that you are up to date (circa the turn of the millennium) on astronomy, botany, cell biology, chemistry, climatology, genetics, geology, oceanography, paleontology, particle physics, quantum mechanics, zoology, etc., etc., etc. Call it Regular Science Theater 2000. It’s journalistic—many chapters involve the author flying out to some distant outpost to interview some expert in that chapter’s field—and very gossipy: Bryson often seems less interested in science than in the wacky eccentricities of dead scientists. But I guess in a way it’s a good thing that this book wasn’t exactly what I expected—after all, I already took the course that actually delivered a short history of nearly everything. This book was absorbing and even entertaining, and the fact that it wasn’t what the title promised kept it from being just a more eloquent version of my class notes.

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tumblr |

this site |

Calendar page |

|||