Gettin’ nothin’ but static on channel me

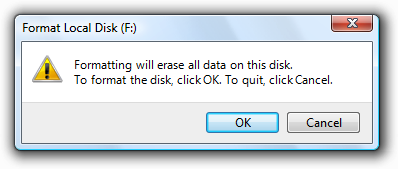

We can start with word choice. For those reading this in the future when this is no longer a thing—or for those reading this in the past when this is not yet a thing—the “canceling” that everyone’s been talking about for the past while is when people take to Twitter and other social media outlets and declare that Taylor Swift or J. K. Rowling or someone is “canceled”. Of course, people can’t actually be canceled. Appointments can be canceled. Merchandise orders can be canceled. Computer operations can be canceled:

But most relevantly, shows can be canceled. Back before anybody and everybody was getting canceled, it was pretty common for people to organize efforts to get media personalities booted from their platforms when they crossed one line or another. These rarely worked: while advertisers tend to be sufficiently skittish about even the slightest whiff of bad publicity that a handful of complaints got many of them to bail on Rush Limbaugh and Laura Ingraham, they both kept their shows. Paula Deen lost hers but soon made a comeback. Bill O’Reilly is the rare exception in failing to regain his prominence after losing his show. The point is, whether or not their shows were canceled, they all had shows to cancel. How do you “cancel” a musician, or an author, or J. Q. Public? Someone once asked me whether I was afraid of being canceled based on something I’d written in one of these articles. I thought, how can I be canceled? I’m not even on the air!

But the very fact that I use the phrase “on the air” reflects that I have a 20th‑century mindset about this sort of thing. (The last time I owned a TV, I did indeed pull in a signal through rabbit ears.) I think that today people make much less of a distinction between someone who has a show and someone who doesn’t have a show. All this “canceling” is taking place on Twitter and other social media platforms—places where you put out a steady stream of content and hope to attract viewers. In this world, everybody has a show. To the extent that these social media streams tend to document the life of the account holders, everybody is a show. And if that’s how you see people—as shows—then it’s only natural to want the ones you don’t like to be canceled.

Queen of the Twitter, the Tumblr, and of the First Men

Years back when I actually clicked around on Tumblr, rather than just using it as a place to announce web site updates, I happened across any number of blogs in which 15-year-olds made imperious pronouncements: You may only select the singular “they” as your third-person pronoun if you identify as gender non-binary, not because you have intellectual objections to gendered pronouns in general! The word “girlfriend” exclusively signifies romantic partners, so straight older women are not permitted to use it to signify their close female pals! It seemed pretty clear what was going on here: when you feel powerless—lacking the autonomy of an adult, identifying with one or more marginalized groups, with stuff going on around you that you don’t like and can’t stop—it’s no surprise that you might like the feeling of issuing edicts in your little fiefdom where half a dozen similarly marginalized younglings take your words as gospel. You don’t have to be a kid to feel powerless, of course. Nearly all of us do, to one degree or another. And therefore much of the structure of traditional society is based on carving out spaces where people can escape this feeling and exercise some modicum of power, according to their station: the boss over the office, and the middle managers over their subordinates; the clergyman over the church, the teacher over the classroom, the chef over the kitchen; the father over the household, and under him, the mother over the children and the domestic staff. The online world has offered another place where you can be the lord of your own little castle, and as your audience grows, handing down decrees is likely to feel that much more empowering. And that feeling may not be entirely illusory.

As far back as 1971, future Nobel laureate Herbert Simon had already coined a term for when the supply of information outstrips the demand: he called it the “attention economy”, which digital media scholar Lisa Nakamura has discussed more recently in conjunction with cancel culture. The idea is that you may not be the network executive who can actually pull the plug on someone’s show, or the theater critic from Birdman who can shut down a play after opening night, but in the attention economy, it’s the target of your cancellation who has the superfluous commodity—content—while you the canceler have the scarce commodity, attention. Ceremoniously declaring to your half-dozen followers that you are hereby going to withhold your attention from someone who has offended you may just be a way to blow off steam, particularly if your target is someone whose claim on your attention was already non-existent (“Woody Allen is canceled!” means more coming from the film critic than from the ninth-grader who has never seen and would never see a Woody Allen movie anyway) or meaningless (“That singer can kiss my $0.0003 in Spotify streaming fees goodbye!”). But say that a while back you recorded a fifteen-second video of yourself copying some dance moves and uploaded it to the spyware app of an authoritarian superpower, thereby collecting a hundred thousand devoted acolytes. Now your pronouncements have the power to help get a canceling campaign trending, and while that campaign will likely be forgotten in a couple of hours, knocked out of the public consciousness by the next outrage, it may be enough to come to the attention of the target and that target’s network, studio, record label, advertisers, or what have you.

“I haven’t seen Pretty Woman but I guess I’ll say it’s my favorite”

This has caused enough of a freakout among traditional media gatekeepers to keep the debate over “cancel culture” in the news even as an organ-trashing virus blazes through the population and paramilitary stormtroopers in unmarked vehicles disappear protesters from the streets of American cities. Right-wingers have seized upon the phrase as the new “political correctness”—a pejorative used to wave away attempts to call them out for propagating systems of oppression. Establishment left-wingers have fretted about the way that running afoul of some new dogma opens them up to being tarred as insufficiently progressive, or as the wrong kind of progressive. There’s a lot of talk about importance of free speech and the danger of stifling debate. There are also those who contend that none of this is new, that people have been getting “canceled” for what they say since time immemorial—to pick an example at random, those who were around in the ’80s may recall the way Jimmy the Greek was swiftly shown the door after offering up some eugenics-based hypotheses for the racial distribution within the sports world. (Those who weren’t around in the ’80s may be surprised to learn that there was a celebrity who went by the name “Jimmy the Greek”.) But the pushback on that came from within medialand. Prior to the rise of online communication, how could people outside medialand make their voices heard? Street protests, sure. Letters to the editor—the feedback on the costume Wonder Man adopted in West Coast Avengers #12 (Sept. 1986) was bad enough that the editors had the creative team change it back. But for the most part the establishment was only answerable to the establishment. The governor pushes for an ill-conceived state tax schedule and the big city editorial boards publish pieces against it. Someone publishes an objectionable book and a couple of highbrow magazines give it scathing reviews. There were plenty of people at home going “boo hiss”, but the targets of those boos and hisses rarely had occasion to hear them. But to the extent that there has ever really been “democratic participation” in a society-wide “debate”, it has generally gone like this: A new issue arises. (E.g., should we go into lockdown? Should we mandate masks? Should we re-open schools?) A vast swath of the public has no firm opinion on it. People with platforms to broadcast positions on the issue do so. Many of the undecided people are then persuaded—not so much by logos or pathos as by ethos. Hey, that person’s on “my team” where these sorts of things are concerned! I guess I’ll go with that side of the issue! The new converts then use their personal connections to persuade others when the issue crops up in conversation. Because virtually no one’s mind has ever been changed without that buy-in. When the counterargument to something you believe is coming from someone out in the world whom you respect, or someone in your life whom you love… then you might find yourself willing to evaluate the logic and consider the feelings on both sides and re-appraise your beliefs. This happens sometimes in classrooms, which is awesome: when the students have bonded, when their commitment to their ideas is only half-set, you will in fact sometimes have a debate between two students conclude with one saying, “You know what? That’s a really good point. I change my mind—you’re right.” But there aren’t many other places where that happens.

And that’s why I can relate to those who signed the Harper’s letter decrying cancel culture. The asymmetries involved in online conversation are frustrating in both directions. Yes, it’s frustrating to see something you disagree with being broadcast from a powerful platform. But on the flip side, if you think you’re being unfairly maligned by 10,000 people… you can’t connect with all of them one on one in order to reason together. There just aren’t enough hours in the day or days in a human lifetime. Now, I don’t have that problem. I am obscure enough that the boo-hisses directed at me tend to come one at a time and years apart. There are trolls, of course, but never mind them. What about the real people? Someone dashes off an email to say that the subject of a Lyttle Lytton entry is no joking matter and I’m a terrible person for putting it in the list of winners, or someone who didn’t like the way I depicted one of my characters writes a post and tosses a “fuck that guy” my way. On the one hand, sad face emoticon, but on the other, it’s kind of an exciting moment: a chance to open up a real dialogue, learn from one another, find some common ground, all that good stuff! So I drop everything and spend a few hours putting together a reply that I hope will get the ball rolling. Here’s what I had in mind—do you think that was a bad idea to start with, or was it a good idea that just didn’t come through? Here are some points where it looks like we already agree—do you see it the same way, or not so much? And… they never reply. People don’t want to discuss their problems with your work. Even the ones who aren’t trolls generally just want to yell “fuck you” and run away.

If you ain’t first, yer last

When I rewrote Ready, Okay!, the top item on my agenda was to improve the character work. That meant making the characters more consistent—readily identifiable by the way they acted and spoke—but at the same time more complex, as I felt like I’d finally grown to actually understand what made each of them tick. For the most part the changes were well-received, but I did get some pushback from a few of the ’00s readers about Echo. In the hardcover, Echo had basically been an exercise in adolescent wish-fulfillment: psychologically troubled enough to seem deep and brooding, but effortlessly brilliant, physically intimidating, and always right on time with the perfect cutting remark. (I did say adolescent wish-fulfillment. It turns out that when you get older you realize that no one ever actually poleaxes the bully with a sufficiently sick burn.) For the second edition, I drew upon an extra couple of decades of having known people who’d gone through some of the things Echo had gone through and, having gleaned some insight into how those experiences shaped them, rewrote her as a more plausible and nuanced character. But some of Echo’s fans didn’t like that. I miss Tough Echo!, more than one person wrote to me. She was my literary crush! I guess this new version is more realistic, but back when this book was important to me, I wouldn’t have cared about how accurate she was as a character study—I needed a role model, and here was this strong, queer woman of color to inspire me! These days we hear a lot of talk, especially in education, about how representation matters, and I guess this was a case in point. Echo gives a whole speech about how much she hates these sorts of labels, but that didn’t stop her fans from using them.

In one of my college classes I was assigned an article by Frederic Jameson. I didn’t understand much of it, and what little I did get out of it may have been a mis‑understanding. Still, I did come away from it with a big idea, to wit: In school, you learn how to appreciate a conventional narrative, which enables you to find much more depth and richness in the fiction you read and the plays and movies you see. But most people don’t actually approach stories that way. Outside the classroom, relatively few people go into a story looking for an insightful exploration of a theme or a precise observation of the human condition. For most, a story is an experience delivery mechanism. What kind of experience? It depends. In the class that assigned the Jameson article, and in others like it, the professors talked about “somatic cinema”: the thrill of fear in a horror movie, the wonder of eye-popping special effects, the triumph and relief as good vanquishes evil. But I think the experience most central to that of the modern culture of narrative reception is that of hanging out with people you think are awesome. Getting warm fuzzies from imagining your favorites getting together: “shipping”. Posting thousands of pictures of Rami Malek to your Tumblr or putting “I just want to marry Foggy Nelson” in your bio. In short, fandom. Now, fandom is just a way to approach narrative. In some cases, it’s the best way. Read “The Bloodstone Hunt” as a literary critic and you won’t find much there, but read it as a Diamondback fan and it’s a goddamn delight. But it’s not the most rewarding way to approach most of the books I assign in my classes. And it’s a terrible way to approach history.

Statues have been coming down lately, some pulled down by protesters, others removed by local governments. These have mostly been monuments to Civil War-era secessionists, but also damaged or destroyed have been statues of segregationists, conquistadors, and various people who owned slaves, which has had some wringing their hands about who might be next on the chopping block. George Washington and Thomas Jefferson owned slaves. Jefferson was by modern standards a rapist on top of that. Abraham Lincoln didn’t believe in full racial equality, and Theodore Roosevelt was a warmonger. So do we dynamite Mount Rushmore? Some say yes! For generations, the conventional view has been that these men made contributions to the nation that outweighed the various charges that can be leveled against them. Now we’re hearing more from those who say that, no, your practices and beliefs can be well within the mainstream of your time and still be beyond the pale; cross that line, and no list of accomplishments can redeem you. So we’ll take your name off the buildings, your statues off their pedestals, and your holiday off the calendar.

This effort didn’t suddenly spring up out of nowhere—there has long been a cottage industry in finding replacements for honorees who have found themselves on the wrong side of history. Local schools have been doing it on a regular basis: out goes David Starr Jordan and in comes Frank S. Greene; out goes Joseph LeConte and in comes Sylvia Mendez; out goes Woodrow Wilson and in comes Michelle Obama. But why do we find it necessary to honor historical figures with schools and statues and holidays in the first place? The fancy word for this sort of thing is “hagiography”—treating historical figures as though they were saints—but in the parlance of our times, it’s history as fandom. Explicitly so, as the school boards declare that they’re looking for “inspirational” figures the same way those “Tough Echo” fans were (and leave it to Palo Alto to decide that no one’s more inspirational than a venture capitalist). It’s an approach to history that doesn’t analyze the actions of historical figures, doesn’t explore the factors in their early lives that ended up shaping the decisions they made, doesn’t trace the legacy of their lives both for good and for ill… instead, it trots out a pantheon to be revered, to be incorporated into young people’s nascent sense of social identity. And while at the moment it is mostly young and mostly left-identified people pulling down the statues, and mostly elderly reactionaries fighting to keep them up—protecting the statues of secessionist rebels seems to be the chief issue of the current president’s re-election campaign, for instance—that doesn’t mean that the young and the left-wing are any better about historical hagiography than the right-wing and old. If anything, they’re worse. After all, it’s the last couple of generations that have brought us “stanning”, a practice in which people gleefully subsume their identities to that of a celebrity and viciously harass that celebrity’s detractors and rivals—selecting a Magneto figure and joining an army of proudly subordinate Toads. Similarly, one of the most popular terms of approbation for young progressives these days is “queen”—a term that suggests not admiration, but fealty. We fought a war of independence whose central premise was that monarchy is bad, but the urge to fall in line behind a revered superior seems to be too deeply ingrained for a democratic mindset to fully take root. So they’re not against hagiography—they just object to some of the figures in the canon. The world of fandom is not one in which someone can just be a person, to be taken for all in all; it’s a world of heroes and villains, and if you aren’t the one, you’re the other. Canceled!

But to those dismayed by cancel culture, some heartening words. All of today’s cancelers will be canceled themselves in their turn, world without end. In a few hundred years, all of us will be considered guilty of one atrocity or another, for reasons that might seem trivial or even absurd today. Are you a vegan? If not, do you really think that your descendants in the year 2264 are going to consider that remotely forgivable? Do you drive a car? Wear clothes? Raise your own children? There’s no predicting how culture might evolve, given enough time, and any of those things might have the youth of 2548 burning you in effigy. That doesn’t mean we forgive the slaveowners, the segregationists, the genocidal monsters of history. Chuck ’em into the lake! Absolutely! We just have to make sure we leave enough room down there for ourselves.

|

|

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tumblr |

this site |

Calendar page |

|||