Stephen King, Diane Johnson, and Stanley Kubrick, 1980

#9 of 28 in the 20th century series

Having finally wrapped up 2014, I return to the 20th century series:

the 28 movies I had listed as my favorites at the end of 1999 but

hadn’t yet written about as of 2016.

We head into the ’80s with The Shining, which I

put on the list despite the fact that I had only seen it once, on a small

TV from ten feet away in the ground floor lounge of my college dorm.

I wasn’t even particularly blown away by it.

But when I put together that list, most of it based on vague memories, I

thought, hey, why not throw it in?

One, it’s by Stanley Kubrick, and two, it takes a heck of a movie

to make you jump out of your seat, not because of the appearance of a

monster or an attack by a serial killer, but because of a cut to a title

card saying “4 pm”.

But after watching it again, I have to conclude that this is not really

for me.

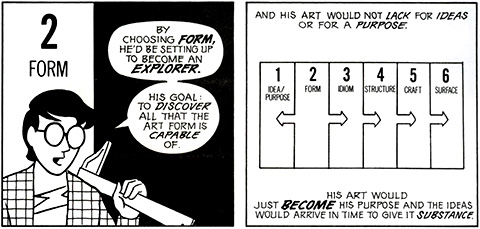

I didn’t dislike it, but it seems to fall into Scott McCloud’s

second category:

This is a movie about the use of a Steadicam (new technology at the time),

about the proper selection of classical music for a film score, and about

the effective deployment of camera angles, zooms, and well-timed

cuts—including, yes, cuts to title cards saying, e.g.,

“TUESDAY”, which still seem to me to be the best thing about

the film.

More broadly, it’s about bringing the innovation of

2001 to

the horror genre, and that is not a genre that does much for me.

As impressed as I was by the arrangement of shots, the content of those

shots was frequently risible.

Like, I think we were actually supposed to find this frame horrifying

rather than hilarious:

Here are some skeletons that the net.kidz of five years ago would term

“spoopy”:

The story is about a guy who looks like Wolverine’s drunk uncle

agreeing to look after an empty hotel deep in the Rockies, dragging along

his Keane-eyed wife and six-year-old son, whose psychic powers (manifested

in the form of an imaginary friend who talks through his

finger—this is unbearable) warn of a bloodletting.

The hotel is almost completely isolated from the world for a full six

months, with the roads impassible and the phone lines down.

The guy goes crazy pretty much immediately, and both he and his son

encounter echoes of the past: a hotel ballroom that is suddenly a

swingin’ speakeasy from the 1920s; the wife and daughters of a

previous caretaker who snapped and hatcheted them to death.

Soon history is repeating itself and it’s our guy who’s

chasing his family around with a hatchet.

Apparently the big debate about The Shining is how to

interpret these echoes of the past.

Is the hotel actually haunted?

In a moment early on that must be very exciting for fans of hoary

clichés, we’re told that the hotel was built “on an

Indian burial ground”—are the disturbed spirits

exacting their revenge?

Or are we just watching the caretaker’s psychological

breakdown?

Some have pointed out that his encounters with the dead always take place

when he’s alone with a mirror.

Having a whole mise-en-scène suddenly not be there when

someone else walks in is a classic cinematic device to suggest madness,

so at times it seems like that’s what the film is trying to

suggest.

But on the flip side, if the ghosts aren’t real, then who unlocks

the door of the storeroom where the caretaker is imprisoned by his wife?

The thing is, this debate seems pointless to me.

Ghosts don’t exist.

(There are those who would deny this assertion, but I would put them in the

same bucket as the flat-earthers and astrology fans—beyond a

certain age, holding these beliefs shows not that you need to be persuaded

but that you are unpersuadable, that you have rejected the logical

principles that would underlie any counterargument I could make.

On this issue, at least, we are what Orson Scott Card would call

“varelse” to each other: unable to meaningfully

communicate.)

Therefore, either the film is about a fictional world with no relevance

to our own, or else the ghost story should be taken as an allegory

encoding content that does have relevance to real-world experience.

It could just be cabin fever.

It could be about alcoholism, anger issues, and writer’s block:

Stephen King has suggested in interviews that he was struggling with all

of these when writing the novel on which the film is based.

Some theories are a little further out there.

Some have said that it’s an allegory for the Holocaust.

Others have taken the burial ground stuff quite literally and argued that

it’s about the centuries of conflict between the United States and

indigenous people.

But in any case, either the supernatural material is a way the

caretaker’s mind has encoded the thematic content, or it’s a

way the filmmakers have encoded the thematic content.

Does it really matter which?

![]()

Tumblr

email

this site

Calendar page