|

Free time is at a premium for me these days, so this is going to be pretty much a stream of consciousness. As the old saw goes, I’m sorry to have written such a long post, but I didn’t have time to write a shorter one. 🙧 1 Every year I ask my sophomores to pick a theme for the second semester, and this year they went with alternate history. The covids have cut our number of instructional days per class in half, so our exploration of this theme will probably not amount to much more than reading a single novel about America falling into the grip of unmitigated fascism. Fortunately, as of this writing that appears to still fall into the category of alternate history rather than current events. Elections always get me thinking about alternate history. They’re rare examples of events whose outcomes can seem good at the time but bad in retrospect, or vice versa—not because of any misjudgment of the candidates, but because of their knock-on effects. Since the Democrats ripped off five straight wins from 1932 to 1948, no party has been able to hold the White House for more than three consecutive terms, and even the three‑peat has only happened once. Within each base, there are reliable voters who turn out every time and unreliable voters who only turn out when they’re dissatisfied—i.e., when their side is out of power. This asymmetry favoring turnover is amplified by the small swing vote, which is not particularly political: it swings this way or that not because some set group of tuned-in centrists has come to view the country’s course as too liberal or too conservative, but because people who don’t fall anywhere on the conventional spectrum have a vague feeling that things are bad and it’s time to shake things up. And apparently the 21st century has been pretty bad! The last time the nation’s “right track / wrong track” polling numbers were in positive territory was 2004. Let’s take a look at the elections since then:

In recent years, it has become a given that 45% of the population will be unhappy because the other side is in power; some portion of the 45% whose side is in power will be disappointed that things aren’t getting better faster; and those sufficiently tuned out not to have any investment in which side is in power tend to be tuned out precisely because things have remained bad for them through several cycles of red and blue. So the “right track” numbers remain deeply underwater and in response the pendulum swings back and forth. Hence my earlier assertion about alternate election results: flip one outcome from a loss to a win, and you pretty much have no choice but to flip a later win to a loss. The question is what sequence makes for the best timing and dodges the worst candidates. When I first started playing this game, the objective was to keep George W. Bush out of the White House. I wrote a whole article back in the day about how it would probably backfire to go the most likely route:

A similar calculus played out in 2016. Yes, in the aftermath of the election, I couldn’t help but wonder whether it might have been better for one of the “good” elections to have gone wrong. How about 2008? Does Donald Trump get any political traction in the early ’10s without a President Barack Obama to serve as a target? We were scared that McCain might bomb-bomb-bomb, bomb-bomb Iran, or that he might drop dead and leave Sarah Palin in charge, but the Democratic Congress would probably have limited the amount of damage he could do at least on a legislative level. And with right-wing austerity leading to an even weaker recovery, plus the unlikelihood of the same party winning four successive terms… that means the Democrats win in 2012, right? Except with Hillary Clinton as the likely nominee, maybe not—or if she does win, and thereby gives Donald Trump a foil to use in building a political following for four years… ulp. So how about 2012, then? A lot of people thought that election was going to be a coin flip. If Mitt Romney wins, he’s the nominee in 2016 as well, and then, win or lose, Paul Ryan’s the favorite for the Republican nomination in 2020, and “President Trump” remains a wacky Simpsons joke. But is that scenario actually better than where we are now? I’m pretty glad that we’re not about to embark upon 4+ years of living in an Ayn Rand novel. And in any case, the calculus I was talking about wasn’t about alternate pasts, but possible futures. In 2016, it seemed like we had the following two options:

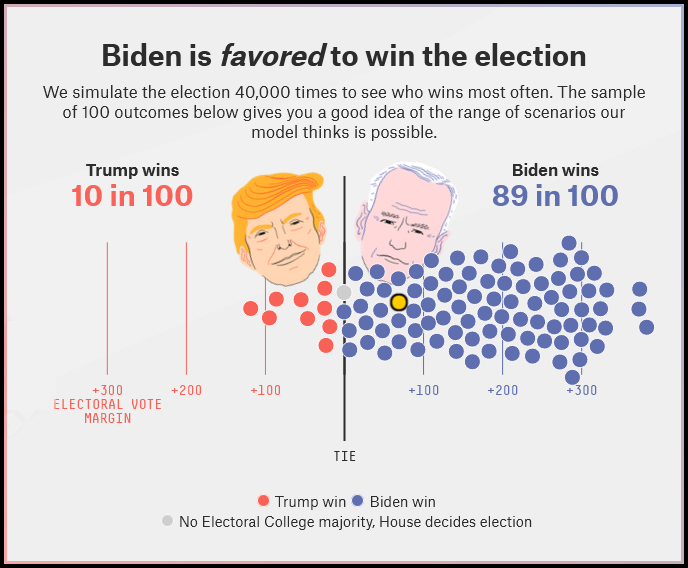

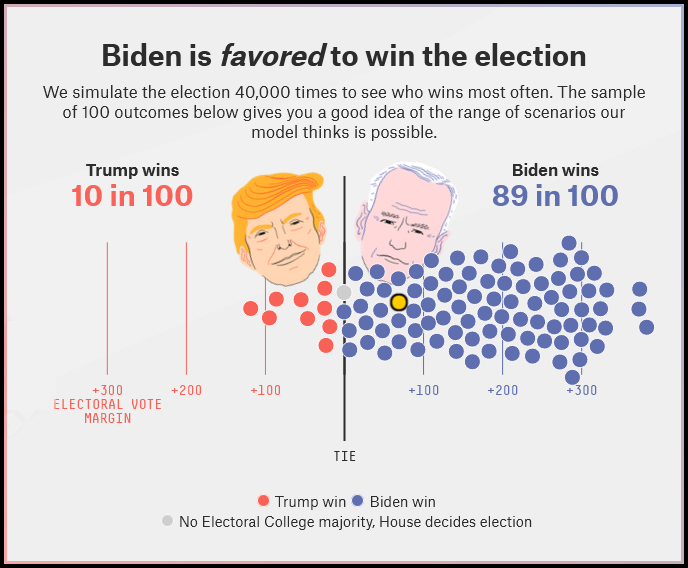

Obviously I was never going to vote for Trump, but I was torn about which of these was the better scenario. I decided that the chance to fill the empty Supreme Court seat—and lock down the Ginsburg and Breyer seats for another generation, assuming they chose to retire—was worth ceding the 2020s to the Republicans. When we wound up in the other scenario, it was traumatic, but once the shock had worn off, that silver lining gave even a hardened pessimist like me something to look forward to. If we could just make it through four years with a narcissistic mobster in the Oval Office, we could look forward to a decade of real progress! …or apparently we could find ourselves right back in scenario one, with Joe Biden in Hillary Clinton’s place. 🙧 2 In the months leading up to the election, the polling aggregators published article after article explaining why 2020 wasn’t going to be like 2016. Polls now weighted for education! They had proven to be dead on in 2018! Joe Biden’s lead was several points greater than Hillary Clinton’s! It was extraordinarily steady, without the swings of 2016! Most crucially, these weren’t 42-to-39 polls with huge swaths of the electorate unaccounted for—Joe Biden was over 50%! Even if every single voter not projected as committed to Biden broke against him, Biden would still win! Good thing, too, because apparently every single voter not projected as committed to Biden broke against him. In the weeks since the election, many partisans for Team Blue have tried to put forward the story that the election was not actually all that close: Joe Biden won by over seven million votes! He won the electoral vote 306 to 232, and per Kellyanne Conway, that’s a historic landslide! And the polls weren’t that far off—here, look at the spread of simulated outcomes on fivethirtyeight.com! The correct dot turned out to be the one highlighted in yellow—that’s not too far from the center of the range of possibilities! Click it to see the map: |

|

|

But as Joe Biden said in the 2007 Democratic debates, let’s stop all this happy talk. This election was terrifyingly close. It will be a long time before I get over that sick feeling watching the early returns from Florida, as a state that the Economist put at 80% likely to end up in Biden’s column instead had its New York Times needle slam over to 95% Trump within moments. This was no “red mirage”: the returns from Miami were indeed dire, came the reports on the ground. North Carolina soon tagged along, and liberal pundits were left to mumble on Twitter about how some of the counties in Ohio didn’t look so bad. Ultimately, of course, the “blue wall” did hold this time: South Carolina’s Democratic primary voters rescued Joe Biden from an ignominious final campaign based on the notion that he was the one candidate who could reclaim the Great Lakes states that Trump had captured in 2016, and their bet paid off. But blue voters spent four years grumbling that Trump’s wins had been a matter of a few thousand votes, and this time around, the same held true for his losses. Have a look:

So, yes, Biden won the popular vote by over seven million votes. But flip 21,600 of those votes—10,400 in Wisconsin, 5900 in Georgia, and 5300 in Arizona—and the 27 Republican state delegations in the House give Trump a second term. 21,600 votes votes out of over 158 million cast! We just made it home with a bullet hole in our hat, people. There are lots of lessons here, some new, some that have been obvious for decades. Let’s look at some of them. 🙧 3 The first lesson is that the structure of the United States government as laid out in the Constitution is terrible. We are taught to treat the Constitution as a sort of secular scripture, or at least as a work of unparalleled political brilliance. It’s not. It was an impressive development for the eighteenth century, but so were steam engines. They are equally obsolete. Take the Electoral College (please). The Electoral College was founded on the notion that a commoner like you would have no idea who might make a good president, but you could hold a vote on who was the smartest guy in your village, and the winner would know. This is not how society works anymore. It is not really how society worked in the eighteenth century either, which is why the Electoral College rapidly evolved into the current system in which electors belong to committed slates and the selection of a slate depends on a winner-take-all vote on the state level (Maine and Nebraska excepted). The thing is, it is not particularly controversial to say that the Electoral College is terrible. People make all sorts of arguments against it:

So, as bad as the Electoral College is, ultimately it is a symptom of a bigger problem: the states themselves. The framers of the Constitution envisioned a country less like what the United States has actually become and more like what the European Union is: a collection of distinct societies whose borders have at least a semblance of logic to them. West Germany and East Germany united because the Germans recognized themselves as a single nation whose partition had been imposed from without. Czechoslovakia split because its leaders determined that to continue as a federation of two clearly separate peoples was no longer viable. And borders may continue to shift over the years to come: Scotland may declare independence from the U.K., Ireland may unify, Belgium may divide into Flanders and Wallonia. Because, again, these are distinct populations. American states are just administrative subdivisions. Does anyone actually believe that North Dakota and South Dakota are such radically different societies that they need separate governors and sets of senators, while downtown Detroit and a sleepy Finnish-American neighborhood in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula form a politically coherent unit? It’s not that the country shouldn’t have subdivisions; on the contrary, I’d like to see states become more meaningful political units with significantly more autonomy than they have today. But that means periodically redrawing borders so that they’re actually meaningful, not ossified accidents of history. A number of people have tried their hands at figuring out where these borders might be. A group at MIT measured what communities emerge when looking at texting patterns, for instance, while a study out of Dartmouth and Sheffield produced a map of megaregions based on commute patterns. It seems the leading figure in this particular pastime is a guy named Neil Freeman, who’s divided up the country all sorts of different ways—perhaps the best known of which is his map of fifty states with equal population. This doesn’t solve the problems with the Electoral College, nor does it even solve the problems with the Senate, whose composition may not reflect the will of the public as a whole. True, at least you don’t end up with preposterous anomalies like twelve senators for New England and two for Texas, or four senators for the Dakotas and one-sixth of a senator for the more populous island of Manhattan. But the problems with the Senate go even deeper. We are taught to revere of the entire Constitution, but hallowed above all else is its system of checks and balances, that exquisite clockwork that pits ambition against ambition and thereby keeps potential tyrants at bay. Yet somehow countries with other systems manage to avoid falling into vicious tyranny—and lately they’ve been doing a better job of it. These countries also subscribe to the startling principle that when people vote a new government into power they actually want that government to be able to do something. In these countries, the idea that the head of government might not command a majority or at least enjoy the support of a majority coalition would be a head-scratcher, since the head of government is defined as the leader of the party that has secured that position. The elected government then implements the program it had successfully campaigned on. But in the U.S., even if the person who takes office as the head of government has actually won a majority of the vote—which, as noted, is by no means a sure thing!—that incoming president may well face a hostile House, Senate, Supreme Court, or all three, and therefore won’t be able to do anything particularly ambitious. That is, for anything significant to get done, four governmental divisions selected by different methods—one subject to gerrymanders by state officials, one gerrymandered by the vagaries of history, and one reflecting the administrations of the previous thirty years or so—all have to be in broad agreement on an agenda, for any one of them can hit the brakes. Some put forward as a feature the existence of these institutional guarantees that nothing can change too quickly. And, yes, we’ve all recently been reminded that a democracy that allows an administration to change things enough that it dismantles the apparatus of representative government will not remain a democracy for long. But the philosophy that keeping things basically the same is inherently good has a name: it’s called conservatism. A system in which a progressive mandate can be thwarted by an opposition that holds a paper-thin margin in half of one branch of government is not particularly representative either. And in a crisis, that can be catastrophic. The metaphor I’ve used in the past is that you’re trapped in a car whose driver is headed straight for a cliff, and you manage to grab the wheel, but discover that it can only move about five degrees. Over time, even this might be enough to stave off disaster. But we have elections every two years. No immediate improvement in people’s lives means a midterm backlash, and in a two-party system, that’s the equivalent of another passenger grabbing the wheel, yanking it in the opposite direction, and assuring that you’re once again headed directly over the cliff. 🙧 4 Of course, that last point is currently academic. There was no blue wave in 2020, and this year’s elections did not produce a progressive mandate. Which brings us to the second and perhaps more interesting lesson of the past few weeks: what the election tells us about where we might be headed. One big question is whether the swinging pendulum I discussed in part one is ever going to stop. So far, prophecies from both the left and right of permanent majorities haven’t panned out on the national level. But that’s an artifact of our flawed political system. Going by the popular vote, we do have a durable consensus: the Democrats have won seven of the past eight presidential elections. But in that span we’ve seen two Republican presidents installed despite coming in second. Will the 2020s make that three in a row? It sure looks that way! Though Joe Biden was able to flip three Rust Belt states back into the blue column this time, Democratic prospects in the Midwest look pretty dismal. Ohio was supposed to be a coin flip, and it wound up at R+8.0. The Economist had Iowa as even closer than Ohio, and it wound up at R+8.2. These states look lost. One poll had Wisconsin at D+17, and while nearly everyone agreed that that poll was an outlier, the aggregators had it at D+8.3. That’s a miss of 7.7 points; if the miss had been 8.4, we’d be headed into a hellscape. Over the course of the previous three presidential elections, Wisconsin went from being 6.7 points bluer than the nation as a whole, to 3.0 points bluer, to 2.9 points redder; this time around, even as its electoral votes went to Joe Biden, it was 3.8 points redder than the country was. So that state will be hard to keep. Pennsylvania, 3.2 points redder than the nation as a whole, won’t be easy. Even Michigan is 1.6 points redder than the U.S. average. The Rust Belt strategy implicit in the Biden nomination may not be viable for elections past this one. The optimists have been expecting these losses to be balanced out by gains in the Sun Belt. But the Sun Belt states aren’t heading left as fast as the Rust Belt states are running right. Biden did flip Arizona and Georgia; time will tell whether those states become Democratic mainstays like Colorado and Virginia, or flukes like Barack Obama’s 2008 wins in North Carolina and Indiana. Arizona actually looks pretty good, with two Democratic senators, and four of its five neighbors (if you count Colorado) having preceded it as red-to-blue states just in my own time as a voter. Georgia may be a fluke, or it may become a southern version of Illinois, the one Midwestern state that Democrats don’t worry about, thanks to the megalopolis keeping it anchored on the blue side of the line. If Atlanta becomes the next Chicago, that could offset some of the damage up north. But North Carolina disappointed: over the past four elections it’s gone from 6.9 points redder than the U.S. average, to 5.9, to 5.8, to 5.7 this time around. That’s glacial. Texas has been moving faster, from 19.7 points redder in 2012 to 11.1 in ’16 and 10.0 in ’20, but that’s still a pace that makes it look like it’s eight years away from being eight years away. And Florida did more than disappoint: it’s trending the wrong way at an accelerating rate, going from 3.0 points redder than the U.S. average in 2012 to 3.3 in ’16 to 7.8 this year. Ouch. So where do the Democratic votes come from in 2024? With the currently projected reallocation of electoral votes, Hillary Clinton’s states plus Arizona and Georgia only get the Democratic candidate to 258 electoral votes. Looks like a lot of advertising money will be flowing into Michigan! But why look forward to potentially worrisome elections in future cycles when the 2020 results were plenty worrisome themselves? Yes, Biden won, but he was projected to have as many as 55 Democratic senators joining him, and that number instead looks like it will be 48. Democrats were supposed to add to their already robust House majority, but instead they came a whisker away from losing it entirely. The Princeton Election Consortium projected that the Democrats would still win the Senate even with a 3.9% polling error, the House with a 4.6% polling error, and the presidency with a 5.3% polling error. Based purely on that, it seems safe to say that the polling error was a gruesome 4.5%. Oh, and Republicans won big on the state level, so redistricting will be a bust and we can expect Republicans to retake the House in 2022 even if most of the electorate votes for Democrats. So much for the value in trading a 2016 win for a 2020 one. I suppose that all hope is not yet lost: as of this writing, there’s a chance that the Senate number won’t be 48, as two seats in Georgia are going to a runoff. So we could have a 50–50 Senate with VP Kamala Harris breaking ties. That would be phenomenal, in that it would put Mitch McConnell in the minority and the Senate might then actually take up legislation passed by the House. Then the Democrats could actually put forward an agenda… that is acceptable to Joe Manchin. Sigh. If the blue team had only won one extra seat, though, it could have enacted bold legislation! …so long as Kyrsten Sinema didn’t think it went too far. So, yeah. Taking control of the Senate would be better than having to cross our fingers and hope that Biden’s cabinet picks win the approval of Susan Collins, Lisa Murkowski, and Mitt Romney, but it won’t mean that we’re getting Supreme Court expansion, D.C. statehood, or even a “Bidencare” package to rescue the Affordable Care Act. And that’s a problem, because it seems pretty clear that Democrats need to pass all those measures and more in order to level the playing field. And it seemed like this was our shot. George W. Bush had been such a disaster that voters handed the White House to a guy whose middle name was “Hussein”, turned the House over to Nancy Pelosi, and gave the Democrats a filibuster-proof supermajority in the Senate. Trump seemed likely to be an even bigger disaster, and he was. True, he didn’t get the nation embroiled in a war, though there were some fraught moments with North Korea and Iran. But he ricocheted from scandal to scandal, one so egregious that even the hyper-cautious House leadership launched impeachment proceedings, and his inner circle of associates regularly went to jail or accepted pardons to escape their sentences. The Bush administration tortured cab drivers to death, leaving an indelible stain on the soul of the nation; the Trump administration took a different tack and tortured babies, separating them from their parents (forever, in hundreds of cases) and locking them in cages. Bush was criticized for launching wars of choice without the backing of a coalition of allies like those his father had assembled; Trump actively drove away our closest allies and curried favor with dictators. And then of course Trump’s handling of the coronavirus made Bush’s handling of Katrina look masterful. (For that matter, so did Trump’s handling of a hurricane.) Like Bush, Trump will be handing his successor an economy battered enough that the new administration’s first order of business will need to be a stimulus package, though the Dow is doing well enough to assure that the gap between the top 1% and everyone else will continue to widen. On top of this substance was style. Bush was widely derided as a fratboy president. But Trump has been both a sociopath and a toddler, his personality so horrifically defective that the most apt comparisons are not with a George W. Bush or a Richard Nixon but with the likes of Idi Amin and King Joffrey. All the ingredients were there for a bigger, and better-timed, backlash than than in 2008. And it’s not like it didn’t materialize: the Democrats got nearly sixteen million more votes this year than in 2016. The problem is that there was a simultaneous backlash to the backlash, as more than eleven million people who hadn’t voted for Trump the first time around decided that, now that they knew what a Trump presidency looked like, they wanted more of the same. Down-ballot, they voted Republican. So did plenty of embarrassed conservatives who voted for the Biden / Harris ticket and then picked Republicans for every other office. Thus do we get a band-aid when what we really need are stitches and rabies shots. As pessimistic as I am, I have to confess that I had bought into the comforting notion that a wholescale realignment was waiting in the distance. Demographics is destiny, right? Forget blue waves—we had a blue tide coming in. The old power structure would try to hang on as long as it could, using voter suppression and gerrymandering and a hundred other tricks, but eventually none of these would be enough, and then we’d be set. I’d even seen one of these realignments from up close. When I was a kid, California was a red state. Between 1948 and 1992, it voted Democratic exactly once, in Lyndon Johnson’s 1964 landslide. But in 1992, it flipped blue and has never looked back. The Democratic share of California’s presidential vote has risen from 46% in ’92 (enough to win in a three-way race) to 51, 53, 54, 61, 60, 62, and 64% over the course of the next seven elections. The 2020s were supposed to be the decade that Florida and Texas made the same leap—after which all four of the big electoral prizes would be blue locks. We’d have a starting map that looked something like this— |

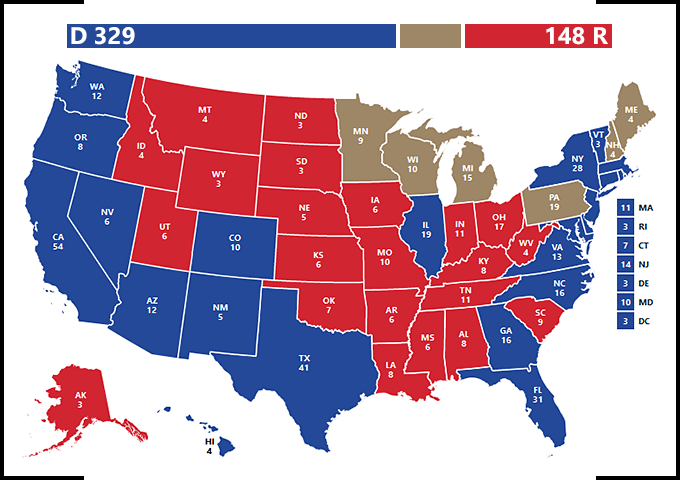

|