|

The winner of the 2015 Skandies was Mad Max: Fury Road. It wasn’t even close: Fury Road received 357 points, 103 points clear of second place. I thought that if I wanted to see what all the fuss was about, I should probably first watch the previous Mad Max films, which I’d never seen. I started at the beginning.

Byron Kennedy, James McCausland, and George Miller, 1979 …But I’m not actually going to talk about this one yet.

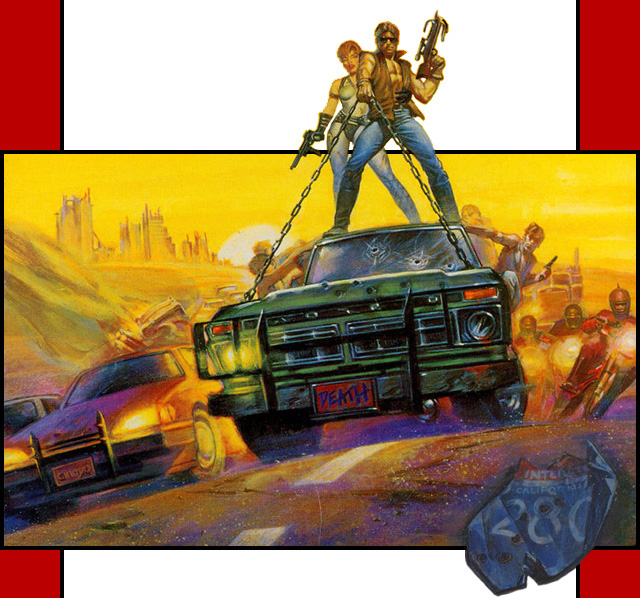

Terry Hayes, Brian Hannant, and George Miller, 1981 This movie was released in the U.S. as The Road Warrior, as Mad Max, despite finding enormous success in Australia and Europe, had flopped in the U.S., and the distributors wanted to market the follow-up as a standalone film, not as the sequel to a movie that most of the potential audience hadn’t seen or even heard of. And director George Miller had suggested that he would be fine with audiences starting with the second film, as he was unhappy with the way the first one had turned out, and viewed the bigger budget for the sequel as an opportunity to do the concept correctly. That concept: the apocalypse has finally come and society has collapsed, to the point that there aren’t even any buildings left, just a few roads cutting through an endless wasteland. The two most advanced units of social organization are, one, a gang of violent scavengers riding around in a handful of salvaged jalopies, and two, a band of survivors trying to build an outpost of civilization around a tiny oil refinery. Their effort is clearly doomed to fail, but for the reluctant intervention of the antihero of the title: Max, a taciturn loner who does end up helping the good guys but claims all the while that he’s just in it for the gasoline. Again, I hadn’t seen these movies before. Similarly, I made it all the way to college without seeing the Star Wars movies (of which, at that time, there were three). They just didn’t sound like they would be my thing. But one evening all my friends were going to watch the entire trilogy on the big screen at Wheeler Hall, so I went with them, and for at least a little while, I thought I actually understood the appeal. At one point, a robot appeared; half the audience went “booooo! hisssss!”; someone called out, “It’s a robot! You can’t hiss a robot!”; everyone laughed. Similar exchanges happened every few minutes. Oh, okay!, I thought. I get it! No one actually takes these movies seriously! Everyone can plainly see that they’re hokey! They’re just having fun reveling in the hokiness! So, thinking that I’d solved the mystery, I was confused to gradually discover that, no, all sorts of people were willing to defend these movies as genuinely good. And Star Wars wasn’t alone in this: I often found that what I considered disqualifying—“How can you take the movie seriously after that?”—were the very elements of a film that appealed to its fans. Consider Mad Max 2. While the desolation of the setting is striking, the most distinctive thing about the movie is that the characters look less like credible hoodlums than like pro wrestlers outfitted by Tom of Finland on a bad acid trip: pink mohawks, football shoulder pads with feathers glued on, steel hockey masks, and lots and lots of leather S&M harnesses with metal spikes. I would scoff that the outfits make it impossible to take the movie seriously, but it seems obvious that the intended effect is to get the theater buzzing, with viewers elbowing each other to snicker, “Ha! Look at what that one’s wearing!”—not to mock the film, but just to express their enjoyment of the show. Adding to my suspicion that the movie isn’t particularly concerned with being taken seriously is that lots of moments are played for lowbrow laughs, as when a bespectacled baddie tries to catch a boomerang, has a bunch of fingers chopped off, and finds that the other members of his gang are all laughing at him. Really, even thinking about the issue in these terms is probably missing the point, as “Can I take this seriously?” doesn’t seem to figure into most moviegoers’ calculus the way that it usually does for mine. And I have to concede that what qualifies as “serious” is an artifice and that I should probably adopt a more expansive standard. After all, the January 6 insurrection was very serious indeed, yet the clowns who stormed the Capitol looked like they would have fit right in with Wez and Humungus. I say that the ability to take a story seriously “usually” figures into my calculus because nostalgia tends to switch off my alarm system. I haven’t watched any Star Wars material (other than the Bad Lip Reading music videos) since that evening at Wheeler Hall, because I didn’t grow up with the franchise and thought the Star Wars movies I did see were silly. But I have been following the Marvel movies and shows (and quite a few of the comics, which I’m not even six years behind on!), which I’m sure many people find equally silly, because when I was a kid the Marvel Universe was my home away from home. And I was surprised to find that even though (as I’ve already said a few times now) I had never watched the Mad Max movies, I did feel a little tickle of nostalgia that I wasn’t expecting. See, the image up at the top of this article is not from a Mad Max poster. It’s from a computer game called Roadwar 2000, which I spent many an hour trying and failing to make any headway in back in 1987. When I first recognized the overlap between Mad Max and Roadwar 2000, I thought it’d be fun to start with that image and see whether anyone picked up on the reference. Then, as I watched more of the films, I started to suspect that there was more than just a little overlap: it became pretty clear to me that the game must have been an attempt to adapt Mad Max as directly as possible without getting sued. I decided to play a few turns to verify my suspicions. And then I decided, goddammit, after 34 years, I am finally going to beat this fuckin’ game. |

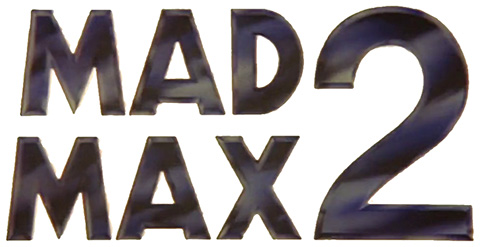

Jeffrey A. Johnson, 1986 “Roadwar 2000 is an exciting game of survival in a brutal land,” declares the back cover, and while I’ll reserve judgment on the “exciting” part, the rest of it certainly captures my experience of the game back in the day: the difficulty level was brutal, and to survive for more than a few turns was an accomplishment. It’s the turn of the millennium, and society has collapsed in the aftermath of a germ warfare attack on the United States. You play the leader of one of the many road gangs battling it out among the ruins, starting off in a randomly selected North American city—one of 121 cities implemented in the game. Your first goal is to get hold of as many vehicles as you can salvage: motorcycles and compact sedans might do at first, but if you want to be able to keep enough supplies on hand to cover any real distance, you’ll need to find a trailer truck. Next, you need recruits: ideally, these will be professional mercenaries or members of smaller gangs, but you might need to resort to the armed rabble, or even to the desperately needy. Make sure you have enough food stashed away to feed your troops, enough fuel to keep your vehicles moving, and enough antitoxin to fend off new variants of the plague. And, of course, you’ll need weapons for your battles against your many enemies: rival gangs, irradiated mutants, and bloodthirsty cannibals. Some cities are controlled by foreign invaders, others by renegade National Guard units, others by religious zealots (or Satanists), still others by the Mafia. Seize control of enough cities to come to the attention of the remnants of the national government, and you may be recruited to crisscross the continent gathering the eight scientists capable of developing a vaccine. (Which ends the game, because of course once the vaccine is developed, everyone takes it and the plague is over.) I made almost no headway when I played this game in the ’80s. I would collect a few vehicles and recruit some troops, and maybe even make it to the next town over, but within a minute or two someone would attack and my gang would be wiped out. (Somehow this dismal experience didn’t stop me from buying the sequel, Roadwar Europa, as soon as I spotted it in a store.) In the early ’90s, I happened across the disk again and decided to take it for a spin. This time I did much better. The chief difference was that I sat down and learned the combat system that had bewildered me in high school. You assign your troops to positions within each vehicle; issue commands for each vehicle to accelerate, brake, turn, or move; order troops where to aim their weapons and receive reports about the results of their volleys; ram enemy vehicles that are within range, or direct individual troops to attempt to climb aboard an adjacent vehicle and seize the wheel; and you do this over and over and over, turn by laborious turn. A big battle could take the better part of an hour. The battles were pretty easy to win—but then you’d return to the map, move one space, and find yourself right back in combat mode. Many weeks passed, with me playing every day, and I had still only found five scientists when I finally gave up. This time around I adopted a different strategy. Roadwar 2000 doesn’t make you spend an hour fighting each battle—you can just tell the program to simulate the combat itself and report the results. You lose a lot of cars and troops that way, which is why I lost every game within a few minutes when I was thirteen. At seventeen, therefore, I never took the quick route. What the wisdom of the intervening decades taught me is that it doesn’t have to be all or nothing. I could fight the first few battles myself, when my gang was just getting started. But once I had a dozen buses and trailer trucks, and hundreds of guys to fill them with, it didn’t much matter if the computer lost a few as I fast-forwarded through the battles. The strategy worked: within a few hours my gang could easily stomp all comers, I controlled dozens of cities, and I had located six of the eight scientists. But I couldn’t find the other two, despite having visited every city, and the “Radio Direction Finder” that I had never managed to obtain back in the 20th century proved to be useless. What I eventually learned was that, even though in half a dozen other cities the “search for people” command had located the scientists in short order, that wasn’t guaranteed. I actually had to do a loop through the cities one more time and hit P dozens of times in each one, watching the day counter click over and click over again, telling the computer to fight a couple of battles for me each of those days, until finally the long-awaited message would appear: “Hello. My name is Pedro Pintero. I think you’ve been looking for me.” And when, after hundreds of lost games in the ’80s, after hundreds of hours of tedious vehicular combat in the ’90s (with long series of keypresses needed just to, e.g., make the tractor complete a left turn), after all the additional tedium of hunting for food and fuel so I could make multiple circuits of a CGA render of the continent, I finally collected all the scientists… the game said, “Now our research can be completed! I am certain we shall succeed. Your name will be revered by all until the end of time!!! Having served your country so bravely I feel you can be counted on to fulfill the one final need of our reconstruction of America. Congratulations, Mr. President!” And that was all. That was the entire reward. Oh well. At least it turned out better than the actual 2000 election.

Terry Hayes, George Ogilvie, and George Miller, 1985 So this one posits that the wasteland is a bit more populous than Mad Max 2 had suggested: there are caravans that follow trade routes to a multi-level city with shops, restaurants, venues for mass entertainment, and a legal system (which is also part of the mass entertainment), and there is also a hidden society of children who live near a crashed jumbo jet, waiting for their messiah, the captain of the plane, to return and take them to the New Jerusalem, i.e., pre-apocalypse Sydney as seen on a View-Master. Eventually these kids make it to the bombed-out ruins of Sydney as sad music plays, which will henceforth be the reel that plays in my head when my favorite contestants lose on Masterchef Australia. I’d had this thought while watching Mad Max 2, but Beyond Thunderdome confirmed it: Mad Max reminds me of Conan the Barbarian. I’m far from a Conan aficionado, but years ago I read Christopher Priest (then Jim Owsley)’s run on the Conan comic, and got a sense of what the character is about. Like Conan, Max is an unmatched warrior of few words wandering a primitive world, with no interest in company yet frequently finding himself among temporary allies, motivated by treasure (in Max’s case, gasoline) rather than altruism yet somehow fighting alongside the good guys far more often than the bad. Though a barbarian, Conan does on occasion find himself in the city; in Beyond Thunderdome, Max does too. Now, if A resembles B, it doesn’t necessarily mean that A was influenced by B; maybe they were both influenced by C. Director George Miller told the New York Times that he had based Mad Max 2 on the archetypes laid out by folks like Carl Jung and Joseph Campbell, and that as a result he’d found that American film critics said his movie was a Western, Japanese critics said it was a samurai film, Scandinavian critics found parallels with the Viking sagas, etc., for all of these were just local manifestations of the same basic tropes. Last year I audited a world mythologies class that went into this notion of a “monomyth” with an impressive degree of sophistication, especially given the time constraints imposed by the pandemic. But one thing I discovered when studying curriculum design for literature classes is that a lot of English teachers nowadays lean pretty hard into a blunter version of Campbell et al., laying out “the hero’s journey” as the key to understanding narrative in general. I gather that a lot of the momentum behind this move has been concern about how the dusty old literary canon is irrelevant to modern students and fails to keep their interest. But teach Campbell, the canny operators confide, and you’re home free: the kids might yawn when you first lay out the framework, but then you show ’em how perfectly it matches up to Star Wars—for George Lucas studied Campbell too—and they perk right up! Except I don’t like Star Wars. I don’t like Conan the Barbarian—I don’t know what better praise of Priest’s storytelling skills I can offer than to say that he managed to make a Conan comic keep my interest. And I didn’t like the 20th-century Mad Max films. Miller himself, reported the Times, said of Mad Max 2 that while he “does not regard this film as frivolous, he does acknowledge its reliance on myth and fantasy and he finds it curious that some people are reading so much into a relatively simple plot.” And, yeah—I’m not sure how much applause is merited for literally following a formula. It’s one thing to study the classic formulas, but when writing teachers argue for following those formulas, saying that millennia of experience have shown that they’re what people find satisfying… I mean, at that point just go teach business school, right? Do you have something you’re trying to express, or do you just want to feed audiences what they like in order to sell tickets? Besides, it seems to me that, in music, it’s often the “wrong” notes you really dig, and the same is true in storytelling. We don’t need another hero’s journey. We don’t need stories already told. Can’t we try to rise bey‑o‑ond myths of old?  Byron Kennedy, James McCausland, and George Miller, 1979 So, back to this. With the second film serving as the series’s calling card, this first film was rebranded, at least in the U.S., as a prequel of sorts: “Hey, you know how in The Road Warrior there’s that whole speech about how it doesn’t matter what Max’s backstory is? ‘Oh, so that’s it. You lost some family. That make you something special, does it? Listen to me. Do you think you’re the only one that’s suffered? We’ve all been through it in here.’ Well, never mind that—watch this movie and learn Max’s backstory!” The setting is very different from that which the sequel would make so iconic: while, yes, this is a world in which road gangs are running riot, it’s not post-apocalyptic, just a bit dystopian. The main conflict is between the gangs and the police force, which means that there is still a police force, operating out of a police station and everything. There are towns with nightclubs, hospitals, BP gas stations. Max lives with his wife and child in a country house with all the latest appliances, and they actually go on vacation and get ice cream cones from a little shop. Crime may be everywhere (crime, crime), but that doesn’t really set Mad Max apart from, say, Taxi Driver. So without the striking setting of the sequel, and without the mythic formula to rely on (for the story is half-baked and oddly circular), how on earth did Mad Max launch a franchise? “It’s pretty obvious why it caught on,” Outlaw Vern answers, “because holy shit these crazy Australian motherfuckers are doing car stunts that you’re not supposed to be able to do. Cars are flipping and skidding out and rolling and exploding, crashing through other vehicles, popping out the other side like a football team through a paper banner. You can’t believe these rookies with no money or local film industry figured out how to do this shit and get it on film and not kill like 50 people.” And… I don’t care about any of that! I wanted to skip past the car battles in Mad Max the same way I was able to skip past their counterparts in Roadwar 2000. And just as most Roadwar players would probably say, wait, the whole point of spending forty bucks on the game is to plow your CGA bulldozer into the rival gang leader’s limo, not to just dick around on the map, I imagine that most Mad Max fans would say that if I don’t care about car crashes, then this movie is totally not for me. And it is totally not. Which made me wonder what I was about to get into with Fury Road. Surely it didn’t run away with the #1 spot on the basis of car crashes…?  Brendan McCarthy, Nick Lauthoris, and George Miller, 2015 #1, 2015 Skandies Man alive, that’s a lot of car crashes. This is the loudness-war version of a Mad Max movie. That is, it is not a different sort of thing; it is the same thing, just with a $150 million budget instead of a $300,000 one. Two hours of virtually non-stop over-the-top violent spectacle. Exhausting. This article sure had a lot of lead-up for not much payoff, didn’t it? And here I thought it’d be hard to imagine a bigger anticlimax than Roadwar 2000.

|

||||||||||||||||||||