(season 1)

Archie Goodwin, George Tuska, Roy Thomas, John Romita Sr., [Tony Isabella, Steve Englehart, Len Wein, Chris Claremont,] and Cheo Hodari Coker, 2016

In 1971, “blaxploitation” was the buzzword in the world of cinema. March saw the release of Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, in which an African-American man, framed for murder by the LAPD, kills multiple cops in self-defense and escapes to Mexico. The film wound up grossing more than a hundred times its shooting budget. Three months later came Shaft, about an African-American private eye who takes on the mob and comes out on top, whose box office success was credited with saving MGM from bankruptcy. Other studios soon jumped on the bandwagon. Superhero comics followed suit. At Marvel, that meant creating a new character. In 1966, when Marvel’s old guard had looked at the company lineup and were concerned to realize that, as Jack Kirby (born 1917) put it in a 1990 interview, “nobody was doing blacks”, the characters they added to address that oversight were T’Challa, the noble monarch of a hidden, technologically hyper-advanced kingdom in Africa, and Bill Foster, a brilliant biochemist who worked alongside Hank Pym and Tony Stark. These were not characters who lent themselves to Shaft knock-offs. So Stan and Jack’s successors came up with a new one: Luke Cage, Hero for Hire! Child of the mean streets of Harlem! One-time gang-banger gone straight, framed as a dope pusher and sent to prison! Escaped after a guard’s attempt to kill him instead turned him super-strong and bulletproof—now on the lam, but helping his community under his assumed name, and making the rent money while doing it! Luke Cage didn’t speak in the language of the royal court or of the laboratory—he spoke in the “jive” of what was then called the “ghetto”, or at least the best approximation that a pale, bespectacled 34-year-old comic book writer from Tulsa, Oklahoma, could come up with. “You wish I was aidin’ mankind like you wanted to, savin’ the universe gratis like the Fantastic Four or the Avengers or some other local super-studs? I lost enough of nothin’ already in this life, man. Girl I loved, lotta good years—no more, baby! You wanna change it… try. But don’t expect me to hang around yellin’ ‘Right on!’ Cops can find me at my office—me, an’ a big mess’a grief!”

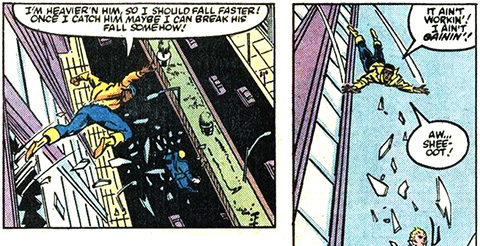

Luke Cage did not become Marvel’s next big breakout character, and the editorial staff tried all sorts of moves to keep him viable. On the theory that his lack of a superheroic handle was the issue, his book was rebranded from Luke Cage, Hero for Hire to Luke Cage, Power Man. He hung out with the Fantastic Four for a bit, then the Defenders. The move that stuck—for a few years at least—was folding his book together with that of another faltering property, creating Marvel’s odd couple of the late ’70s and early ’80s: Power Man and Iron Fist. Iron Fist was the graceful kung fu master, Power Man the undisciplined brawler; Iron Fist was the fair-haired heir to an immense fortune, Power Man the product of the slums; Iron Fist was the innocent idealist who would ask the villains to please stop disrupting the harmony of all living things, Power Man the streetwise cynic. Streetwise, but book‑stupid, and writers had an unfortunate tendency to portray him as a buffoon. For instance, here’s Marvel editor-in-chief Jim Shooter writing him in 1985:

Eventually, Marvel gave up: though the concluding issues by Christopher Priest (then writing under the name Jim Owsley) made up one of Marvel’s best runs of the ’80s, Power Man and Iron Fist was canceled in 1986, and Luke Cage was quietly shuffled to the background of the Marvel Universe. Marc McLaurin tried to revive him in the early ’90s, this time putting him in regular clothes instead of a tiara and giant chain, and ditching the “Power Man” moniker. Lasted twenty issues. John Ostrander tried to revive him in the late ’90s as part of a new Heroes for Hire title. Lasted nineteen. He was thrown into a few other teams as well: the Secret Defenders, the Marvel Knights. Then Brian Bendis got hold of him.

During the first two decades of the new millennium, Bendis wrote virtually every Marvel title at one point or another, and everywhere that Bendis went, Luke Cage was sure to go. His first stop was in Alias, the flagship title of Marvel’s adults-only MAX imprint, in which, notoriously, Luke Cage essentially served as the punchline to a raunchy joke. How would Bendis, with the freedom to push the envelope afforded him by a line of R‑rated comics, show what a self-hating basket case his new character Jessica Jones was? Har har, by having her let the big dumb blaxploitation guy fuck her in the ass! A year later, Bendis was writing Daredevil, and had Luke playing bodyguard to Matt Murdock. When Alias gave way to the PG Jessica Jones vehicle The Pulse, Luke showed up in that one too, now in an accordingly more wholesome role as Jessica’s actual boyfriend. At the same time, Bendis rolled out a series called Secret War to showcase his ability to juggle a bunch of Marvel’s big names—Spider-Man, Wolverine, Captain America—but led off with Luke Cage. On the heels of that series, Bendis was tabbed to reboot the Avengers, and he made Luke Cage a founding member of the revamped squad. Ah, but for his next trick Bendis took the helm of a big event series called House of M, in which the Marvel Universe was replaced by an alternate reality in which mutants reigned supreme with Magneto at their head. An X‑book, then, and Luke Cage has nothing to do with the mutants, right? Right. So much so that Bendis wrote in a Human Resistance Movement led by, you guessed it: Luke Cage! “I realized that I’m maybe the only person right now who thinks Luke Cage is the coolest person in the Marvel Universe,” Bendis explained. “I made it my doctoral thesis to tell the public why Luke Cage is the coolest.” And if the goal was to raise Luke’s profile, it worked! The people behind the Marvel Cinematic Universe seem fixated on the era when Bendis ruled the roost—even when they aren’t adapting his own characters like Jessica Jones and Daisy Johnson, they’re running with stories from the same period, such as the Winter Soldier arc and Civil War. And if those are the comics you’re thumbing through trying to figure out who’s big enough to headline a TV show, it’s hard to miss that Luke Cage is front and center in practically every book.

One problem. Bendis explained that a big part of moving Luke Cage to the center of the Marvel Universe consisted of “kind of scraping off all the blaxploitation elements that were being used by other writers,” grumbling that “even in the late ’90s he was still saying ‘funky honky’ and stuff like that”. This was easy enough for Bendis to do, as he has demonstrated the ability to write only two characters: (a) Spider-Man and (b) “the Bendis character”, i.e., literally everybody else. You know how Secret War was supposed to showcase Bendis’s ability to juggle a bunch of different characters? Bendis can’t actually do that! Whether it’s Thor or the Thing, Wolverine or the Wasp, Bendis uses the same voice. In Luke Cage’s case, Bendis does throw in the occasional “a’ight”, which I’m not sure actually constitutes a substantial improvement over “funky honky”. So, yeah—Bendis did indeed scrape “the blaxploitation elements” off Luke Cage, to the same extent that he scrapes every distinctive attribute off every character who isn’t Spider-Man. This allowed the TV writers to depict their Luke Cage as a level-headed, well-spoken role model and still say that this was a reasonable approximation of the guy from the comic, even though he’s miles away from the ’70s/’80s version. But what story could they tell? Not the story of his relationship with Jessica Jones—they dealt with that over in her series. Not any of his Avengers stories, because in the MCU circa 2016 he’s not an Avenger yet. Not any of his Power Man and Iron Fist stories, because in the MCU circa 2016 Iron Fist had yet to be introduced. No—this is a solo series, so they had to go all the way back to his solo title. That means that not only are we right back in the “blaxploitation” era, but also that while the first two seasons of the Daredevil series gave us such classic antagonists as the Kingpin (approximately 500 appearances in the comics prior to the debut of the show), the Punisher (nearly 1000 appearances), and Elektra (around 300), the first season of the Luke Cage series gives us Cottonmouth (a grand total of seven appearances prior to 2016), Shades (thirteen appearances), Black Mariah (three appearances), and Willis Stryker (ten appearances), who goes by the name Diamondback but who as far I’m concerned had long since surrendered the rights to that name to Rachel Leighton (147 appearances). Let me put it this way. The series begins with a barbershop conversation about the New York Knicks’ 2014–15 season, when they went 17–65. Having the Marvel Universe at your disposal and making this lot into the villains is like having the rights to make a series out of any NBA team in history—Steph Curry’s 73–9 Warriors, the Jordan Bulls, Bird and Magic’s Celtics and Lakers of the ’80s, any LeBron superteam—and choosing those Knicks. The Luke Cage villains are the Quincy Acy, Cleanthony Early, and Langston Galloway of the Marvel Universe.

In a vacuum, though, I guess they’re fine. One thing about Daredevil is that, since the Frank Miller days, he’s been positioned as the protector of a specific neighborhood—like, instead of Captain America, he’s Captain 34th to 59th Street West of 8th. You get mugged on 61st Street, and, well, you’d better hope that Spider-Man happens to be swinging by, because Daredevil ain’t care. This show similarly sets up Luke Cage as the hero specifically of Harlem, but at least Harlem is an internationally famous neighborhood with a distinct cultural tradition. Like Daredevil in the first season of his show, Luke takes on organized crime: all the villains are involved in one way or another with the same Harlem-based crime family, which specializes in gun-running but also has control over a legitimate nightclub and a seat on the city council. Luke is trying to keep a low profile, but events force him to the conclusion that with great power comes great responsibility, and he decides to take the family down. Here’s where the series diverge: Daredevil may have super-senses and ninja training, but he is regularly up against other ninjas and, even when he’s not, he only has standard human physical resilience (though in the MCU that is a highly wonky notion, with ordinary people shaking off head blows that should cause devastating brain damage). Daredevil is therefore regularly beaten to a pulp. But Luke Cage’s whole gimmick is “unbreakable skin”. He’s bulletproof and can punch his way through thick concrete walls. It is a different feeling to watch him stride into a fortress, knowing that even if the baddies get the drop on him, there’s nothing they can do to him. The writers have to posit super bullets made of exploding alien metal just to give Stryker a chance of wounding him and raise the stakes a bit.

Of course, another classic move when you’ve got an invulnerable protagonist is to put the supporting cast in danger instead. Here the main supporting player is Misty Knight, whom I knew from the comics as one of the Daughters of the Dragon, a pair of martial artists in Power Man and Iron Fist’s orbit (in fact, Misty dated the latter, and credit to Marvel for publishing an interracial couple in 1977). Here she’s still with the NYPD, providing the perspective of a good cop in a series built around the notion that we need vigilantes because half the police are compromised by the baddies and the other half are essentially powerless—the old routine of arresting a villain who yawns that “I’ll be back on the street in an hour,” and is. The other big supporting character who pops up is Claire Temple, as seen in both Daredevil and Jessica Jones; she actually is originally from Luke Cage’s solo book, and is great here. She gets to do more than just patch-up jobs this time: she figures out how Luke’s powers work, and her presence as a potential love interest for the title character and as a good judge of character allows Misty the freedom not to be those things, which makes Misty more interesting than she might otherwise be, even as Claire is much more likeable.

Anyway—a fairly solid show overall, though there’s some herky-jerky pacing and some weird event triggers. For instance, we learn that Luke and Stryker have some kind of past together, but Luke can’t figure out why Stryker is so obsessed with destroying him. So he returns to their hometown in Georgia, where with little provocation he abruptly has a flashback to a childhood memory and announces that, looking at that memory with adult eyes, he gets what was going on in a way he previously hadn’t, and now fully understands Stryker’s fixation. Not exactly an exhaustive process of piecing together clues. I was also struck by the way the show makes a big point of distancing itself from elements of the series—not just the yellow shirt (though it seems like all these shows have a scene in which the lead character sees his or her comic book costume and says something like “I’m not wearing that! I’d look really stupid!”), but also the original title, as Luke says flat out, “I’m not for hire.” In the comics, Misty has a bionic arm; in the TV show, her arm is nearly shot off, and I expected that the bionic arm was on its way, but instead she is fine again in a ludicrously short time. Maybe a setup for the future, but it felt like the creators were just tweaking audience members familiar with the source material. Finally, a word about the music. I’ve been struck by the way some other Marvel series have included some pretty obscure songs that I actually like—I first heard that Sleigh Bells song on Jessica Jones, and I think S.H.I.E.L.D. was playing an old Distillers tune at one point. Luke Cage, on the other hand, puts a lot more emphasis on long musical sequences. They are mostly rap, and like Lars from room 303 in my sophomore year dorm, all rap I hate. But I have to say, the theme music is quite good! I did a little bit of reading about it, and apparently there was a little switcheroo involved: yes, Luke Cage was created in response to blaxploitation films, but when the composers got out of their time machine in the early ’70s to check out the source material, they also headed into the next theater over and took in a spaghetti western.

|

|

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tumblr |

this site |

Calendar page |

|||