|

|

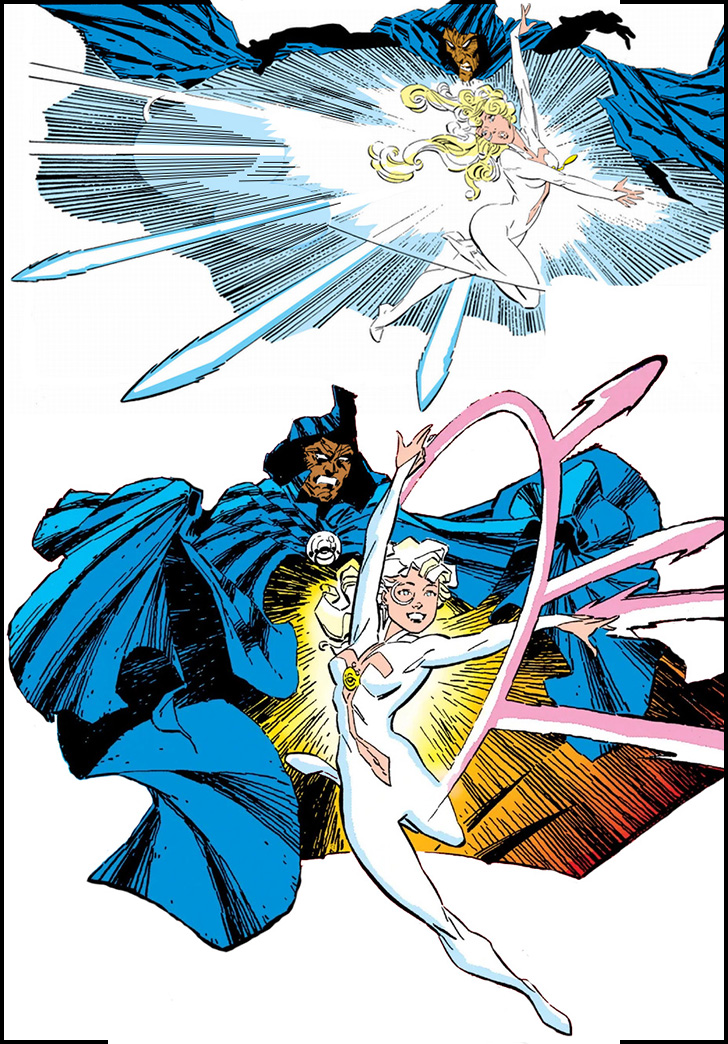

I didn’t expect that we’d be getting anything like these

images on the show.

They didn’t seem like the sort of visuals that a TV budget would

allow for, and they also suggest a partnership of long standing between

the two characters, whereas I figured that this would be one of those

Runaways deals in

which it takes all ten episodes just for the heroes to get a grip on

their powers, have their first adventure, and establish a semi-stable

status quo.

Sure enough, the show does start with the heroes’ origin, and

it’s miles away from the comics version—quite

literally, as we spend the entire season in New Orleans.

This is not an arbitrary choice of locale, as geography is woven into

the storyline.

Take the TV origin: no Port Authority, no Mafia, no experimental

drugs.

Instead, Roxxon (one of Marvel’s foremost evil corporations)

is using one of the many offshore oil rigs that dot the Louisiana coast

to drill for a mysterious energy source when the rig is rocked by a

couple of explosions.

The first one leads to a pair of disasters: the car in which Tandy is

riding goes off a bridge and plunges into the water, and Tyrone’s

brother Billy, held at gunpoint by a racist cop, gets shot when

the cop gets startled.

Billy’s body also tumbles into the water, and Ty jumps in after

him, so both he and Tandy are in the water for the second explosion,

which powers them up—though they don’t know

it.

See, in the comics, Ty and Tandy are sixteen when they get their

powers.

On the TV show, they’re half that age.

But their powers don’t activate until

and their hands touch.

Zap!

They both go flying, and now they’re superheroes.

Their powers are different from in the comics, but to my relief,

they’re still not about punching.

Tyrone can still teleport, though he discovers that when and where he

goes is largely out of his control without some sort of cloak to

wear.

But other than the special effect of inky swirls, and one scene in the

season finale, there’s nothing about the dark dimension, nothing

eating away at him unless he’s fed by Dagger’s light.

And apparently the showrunners didn’t have the effects budget to

make this Cloak look like comics Cloak—he’s basically

just a kid in a hoodie.

He does have the power to see people’s fears with a

touch: time stands still as he finds himself in symbolic

nightmare sequences that are pretty cheesy, but which I kind of liked

for their cheesiness—I found them refreshing throwbacks

after watching too many movies with CGI scenes that look like video

games.

On the flip side, Tandy has the power to see people’s

hopes—and there’s nothing

like that in the comics, so far as I know—in similarly

cheesy dream sequences.

She can also create daggers of light, but they don’t purify souls

on the TV show; instead, they’re, y’know, daggers.

She stabs people with them and those people scream and bleed and go to

the hospital.

She can also effortlessly cut through metal with them.

And they look awesome.

I have a lot of criticisms of this show coming up, but I should note

right up front that all in all I liked the show, and a big part of the

reason I liked it is that my inner eleven-year-old saw a real life

Tandy Bowen summoning up light daggers and they looked totally

rad.

I don’t know what my eleven-year-old self might have made of

Tandy’s characterization on the TV show.

Certainly there’s a lot more

characterization of both Ty and Tandy on the show than in the

comics.

At least as written by Bill Mantlo, there’s not much more to

Cloak than Big Talk about their grim duty to strike at evil wherever

it lurks, while Dagger whines about how she just wants to put their

mission behind them and live a normal life (which she can do in a way

).

A lot of the characterization is done by third parties telling us what

we’re supposed to think of the characters: “She’s so

young, so innocent!” Spider-Man thinks while fighting with Dagger

in her second appearance. “I want to shelter her—not

slug her!”

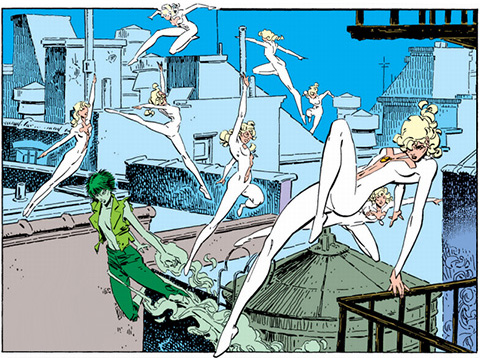

Actually, a lot of the dialogue in these early appearances reads like

Mantlo trying to communicate what the art does not: “I’d

forgotten how beautiful, graceful… and

fast Dagger is!” Spider-Man thinks,

adding out loud, “Dagger, you’ve got all the moves of a

prima ballerina!”—while Ed Hannigan draws her to be

built like and lumber around like the She-Hulk.

It wasn’t until Rick Leonardi started penciling the character

that we finally saw the slim, agile dancer the

dialogue had been describing:

But making Dagger’s personality match what other characters said

about her was Mantlo’s responsibility, and he never really did

pull it off.

So it was fine by me that the creators of the TV show basically made up

a new personality for her out of whole cloth.

TV Tandy is a

.

Her primary modus operandi is to go to a bar in an affluent area, wait

for a rich guy to hit on her, go back to his place, slip him some

roofies, and steal his stuff: money, valuables, drugs.

(TV Tandy likes Xanax to roughly the same extent that comics Tandy

hates heroin.)

But this isn’t her only trick.

As a young, pretty blonde, “People let me in,” she explains

to Ty, and she has a knack for seeming to belong wherever she goes: all

she needs to do is show up wearing the right clothes and knowing the

right names, and she easily infiltrates high society weddings

(“I’m a distant cousin!”), corporate offices

(“I’m the new intern!”), talent agencies (“I

have 17,000 followers on Instagram!”), and takes what she wants.

As far as she’s concerned, “The world has stolen from me

my whole life,” and she feels like her thievery is just a matter

of getting back a little of what’s hers.

This is a source of some friction with TV Tyrone, a Catholic school

student whom Tandy initially dismisses as a “choirboy”.

But though he is generally buttoned-down and complains of the pressure

on him to always be “perfect”, he has anger issues that

threaten to get him expelled from school, so our heroes aren’t as

dissimilar as all that.

Good thing, too, because while I acknowledge that “oh noes Ty

and Tandy aren’t getting along right now” is one of the

most frequently recurring Cloak and Dagger

plotlines, one of the main things this concept has going for it is

the heartwarming bond between the two characters—the

way they’re not family,

not romantically involved, yet absolutely

devoted to each other.

I was impatient for the show to finish going through the motions of

having them meet and argue and whatnot so they could finally get to

that spot.

In the last episode Tandy declares that “for some reason

life tossed us together and mixed up our mojo”, which is a pretty

good start!

Okay, on to the criticisms:

The show uses songs as its musical score; the songs

are bad and very obtrusive.

Scene after scene was more or less ruined by these fuckin’

terrible songs.

Particularly impressive is that the songs came from a wide variety

of genres, yet were still pretty much uniformly bad!

While Pattern

24 states that I enjoy a geographically grounded narrative, and I

do, I wasn’t a huge fan of all the paeans to New Orleans.

New Orleans is a hole.

One element of the New Orleans setting that I found particularly

grating was that the creators decided to weave voodoo into the

storyline.

Now, sure, start up a Brother Voodoo series and I guess my completism

will probably force me to watch it.

But expecting me to accept that Cloak and Dagger’s powers are

real and that voodoo is

real—that’s one too many buy-ins.

Finally, the show frequently goes meta.

It’s bad enough when it’s some incidental fourth-wall

breaking, like when one female character chides another for making

them fail the Bechdel test.

Or when one character gets literally fridged to advance the arc of

a supporting character, Brigid O’Reilly—to those

outside the world of comics, it’s just a random moment of

gruesome horror, but to those familiar with long-running debates in

the world of superhero fandom, it’s clearly a shout-out to

Gail Simone.

“Look, Gail, we subverted the trope! Ain’t we

clever??”

But worst of all is that an entire episode (the ninth out of the ten)

intersperses the plot and character beats with scenes of an English

teacher lecturing to a class about the formula of “the

hero’s journey”.

What on Earth could possibly be the point of that?

“Look, here’s the formula I’m slavishly

following!”

The best answer I could think of is that it’s a

Pattern 28 thing, in

which the creators mistakenly think that lampshading the formulaic

nature of their episode will make its formulaic nature okay.

The alternative is that they’re proud of how they’re

following a formula beat by beat—“Look! Maximum

narrative power!”—and that is too dismal a

thought to bear.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

comment on

Tumblr |

reply via

email |

support

this site |

return to the

Calendar page |

|

pop-up cartoon by Kate Beaton

|

|

|