Blue is about a woman named Julie. The film opens with a car crash in which her husband and young daughter are killed. Julie herself is hospitalized, and when she learns what's happened she breaks into the pharmacy and dumps a bottle of pills into her mouth... but can't bring herself to swallow. Her husband turns out to be a famous composer, so Julie watches the funeral from her bed on a tiny LCD television. Julie's fingertip stroking the small cluster of pixels that represent her little girl's coffin is one of the saddest things I have ever seen in a movie. Julie's injuries heal. She is now on her own. She has no close friends. Her only family is a mother ensconced in a nursing home, suffering from the middle stages of Alzheimer's. She sells all her possessions, changes her name, moves to a small apartment elsewhere in town, and develops new habits: a swim at the club, a coffee and ice cream at the café. She is determined not to get involved again — not to get tied down to anything or anyone who could be ripped from her at any moment. Occasionally someone from her old life gets hold of her and wants to talk with her. "It's important," one of them says on the phone. "Nothing's important," she replies. I imagine that most Westerners, or at least most Americans, would find this state of affairs pathological. Kieslowski seems to agree. The second half of Blue is about Julie reconnecting to her old life: bonding with her dead husband's pregnant mistress, taking his assistant as her new lover, finishing his last piece of music. (There are suggestions she was the real composer all along.) The film concludes with the aria she's written: "If I have not love, I am nothing." But here's a counterpoint:

That, however, will have to wait till I get to Red.

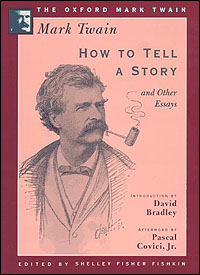

I hadn't been expecting the word "Tell" in the title of How to Tell a Story and Other Essays to be quite so literal, but the title essay is in fact not about writing — it's about how to deliver a funny story on stage. It is a bit strange to remember that Twain was known, especially initially, more as what we would today call a standup comedian than as a writer. The other essays in this book are a mixed bag. Four of them — that is, half, including the longest one — are essays flaming other writers' work. "Fenimore Cooper's Literary Offences" and its attack on the Leather-Stocking Tales is legendary, but few have heard of "In Defence of Harriet Shelley," in which Twain takes on a biography of the poet and its insinuations about his first wife, or of Twain's two articles tearing into Paul Bourget. They mainly serve as reminders that Twain, while a proud rascal in many ways, was also kind of a prude, increasingly so as he got older. So here we get paeans to the chastity of American women and scathing criticism of William Godwin for suggesting that unmarried couples should shack up. I'm glad a travel book is up next.

Return to the Calendar page! |