Neil Burger and Steven Millhauser, 2006

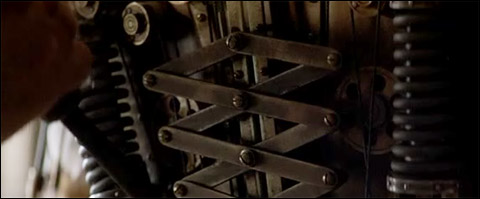

The Prestige Ah, coincidence. In the late 1990s moviegoers were treated (?) to not one but two biopics about Steve Prefontaine. One would have been insufficient! In 2006, instead of 1970s track dudes we had turn-of-the-century magicians. Not only that, but each film featured one of the two most recent alumnae of Esquire magazine's Sexiest Woman Alive feature. And that kind of sums of the difference between these two movies. Scarlett Johanssen appears in The Prestige. She is a movie star, and The Prestige is a major film. Jessica Biel appears in The Illusionist. She is a sitcom actress, and The Illusionist is an instantly forgettable trifle. I like to watch movies knowing virtually nothing about them other than that someone recommended them. If you are similarly inclined, be warned that I am about to spoil most of both these movies. If you think you might want to watch The Prestige, stop here and come back later. (If you think you might want to watch The Illusionist, read on so I can save you two hours of your life.) Let's get The Illusionist out of the way first. A teenage working-class boy in Austria-Hungary catches the eye of a pretty aristocrat girl, but her chaperones keep them apart. He travels the world and comes back years later as a stage magician, successful enough to perform for the Habsburgs. He finds that his one-time paramour is engaged to a mustache-twirling muha-muha prince. Then things seem to go horribly wrong, but ha ha, it was all a ruse on the part of the illusionist. Who would have seen such a shocking twist ending coming, other than everyone who's seen a movie in the past fifteen years? The Prestige also has a twist ending — Welcome to the Anytown USA Multiplex! Twist endings in all 18 theaters, each more twisted than the last! — but it has more going for it than the empty puzzle-box of The Illusionist with its star-crossed ciphers and cartoon villain. The Prestige is about the rivalry between two stage magicians, Alfred Borden and Robert Angier. Initially they and Angier's wife all work for the same show, until Borden's recklessness gets Angier's wife killed onstage. They go their separate ways. Borden starts his own show, which Angier sabotages, disfiguring Borden; Borden returns the favor, and their competition turns into an arms race. Borden premieres a new trick that Angier can't figure out: he enters one box and immediately appears in another on the other side of the stage. Angier is able to duplicate the feat by using trap doors and a lookalike, but that leaves him under the stage while the lookalike receives the applause. And he's sure Borden isn't doing it that way. Angier's obsession with learning the secret makes him such an easy target, so desperate for an answer, that Borden manages to convince him that the illusion is real. And Angier is so deranged that he goes halfway around the world to the recently closed American frontier, where Nikola Tesla has set up shop in the Colorado mountains, to get the world-famous inventor to build him a machine like the one he built for Borden that actually duplicates him. This is a wild goose chase, of course. Tesla never built such a machine for Borden. He's never heard of Borden. But he builds one for Angier anyway. "With a sinking heart," Roger Ebert writes, "I realized that The Prestige had jumped the rails, and that rules we thought were in place no longer applied." Why sinking? Why not soaring? Who wants a movie on rails? Ebert's remark reminded me of one person's complaint back in 1998 that Photopia really "bothered" her because of the "abrupt switch in genre": "Huh? What? Did I miss something? Real-life to fantasy? [...] Sudden appearance of fantasy where I was least expecting it, threw me. I stopped 'buying' into it." My response at the time: "I took a class on fantasy literature when I was at Berkeley. Pretty much every book on the reading list was just like this: combining gritty realism with fantasy, and throwing into question the boundaries between the two. That's what makes it interesting. That's what makes it literature and not genre hackwork." I still basically endorse that and think it applies very well to The Prestige. The story of the dueling magicians was reasonably diverting. Tying it into the rivarly between Tesla and Thomas Edison made it very interesting. And then that one element of the fantastic made it literature. Mike D'Angelo, who initially gave The Prestige a blah review and then saw it again and upgraded it to his #1 movie of 2006, wrote that "A second viewing reveals the real trick here: the way the Nolan brothers tackle the existence of God without once using that word." He didn't say how, but I think I can reconstruct the argument: at the end of the movie, Angier says that the reason he devoted his life to stage magic was that "The audience knows the truth — the world is simple, miserable, solid all the way through — but if you can fool them, even for a second, then you can make them wonder, then you got to see something very special... you really don't know? It was the look on their faces..." And while he's talking about stage magic, really he's talking about religion. Deep down, everyone knows that there are no miracles in the universe, but they go to church because they want to be fooled, because, as Borden says, lightly punching a grimy London wall, it takes them away from all this. If this is indeed the central metaphor, then it's clear how D'Angelo gets God out of Tesla's machine. I think that interpretation holds up, but I would add something else to it.

...well, that's clearly the stuff of fantasy. Curse you, filmmakers! You broke the rules! Hey, you know what else was the stuff of fantasy before Tesla was born? Holes in the wall that you could plug devices into to make them run by themselves. I watched The Prestige on a little box that can show moving pictures on a bright screen, the same little box that I am now using to display the words I am typing, words that I can effortlessly move around by pushing a button and spinning a ball. It is powered by alternating current. Alternating current was developed by Nikola Tesla. The duplication machine in The Prestige is miraculous, yes. But it is really no more impressive than any of the miracles Tesla did bring about. We now take those for granted, so the story invents a new one, one by which we will be appropriately awed, the way we should be awed every time we turn on the radio. The promise of The Prestige is that what we fake today, we will do tomorrow. And incidentally, its twist ending functions differently from that of The Illusionist. It's not just an empty exercise in mentally reordering what we've seen: "I thought he was sad, but really he was just pretending to be sad!" What the ending of The Prestige does is retroactively add resonance, literary quality, to what had come before. And that's not all. See, in The Illusionist, we are supposed to interpret what we're seeing one way and then be surprised when it turns out that something else was going on. In The Prestige, we are supposed to interpret what we're seeing one way, and then be surprised when it turns out that something else was going on, and then be horrified thinking about the implications of the real explanation. Here I'd thought Spoorloos was hard to take. This was a hundred times worse.

Return to the Calendar page! |