William Monahan, Siu Fai Mak, Felix Chong, and Martin Scorsese, 2006

Premise

Evaluation I did find myself thinking, "Okay, this can't just be about the mob — what's the movie really about? What are we possibly supposed to get from yet another mob story?" And thinking it over, I found that a few exchanges really stuck out. The first was when the undercover cop asks Costello why he does this. It's the same question I asked about Goodfellas: Why give up any sense of security in exchange for a pink Buick or a tacky apartment? For Costello, at least, it isn't the money: "I haven't needed the money since I took Archie's milk money in third grade. To tell you the truth, I don't need pussy anymore, either." So then why? Why make yourself a target of the cops, other mobs, ambitious underbosses? In the end, the answer seems to be as simple as this: Costello is an asshole. Being a crime boss is just an outlet for his supreme assholiness. And he isn't even necessarily the biggest asshole in the movie: competing for the title is Staff Sergeant Dignam of the Special Investigations Unit, played by Marky Mark. Dignam is ludicrously abusive to everyone he encounters. Without an official power structure to back him up he would very likely get shot in the face very quickly. So police work is his outlet for his assholish nature. The difference between the criminal and the cop is that Costello's chaotic evil and Dignam's lawful evil. (Maybe neutral evil. I don't play D&D.) When the undercover cop, Billy Costigan, asks the psychiatrist whether the cops she counsels cry, she says yes, they do "if they've had to use their weapons." Costigan replies, "Let me tell you something — they signed up to use their weapons, most of them, all right, but they watch enough TV so they know they have to weep." It's actually a pretty brave argument! Because when you say that both cops and criminals are violent people who happened to grow up in different neighborhoods, the logical extension of your argument is that the "terrorists" we're supposed to hate and the "troops" we're supposed to support both signed up to kill foreigners — they just happen to come from different neighborhoods.

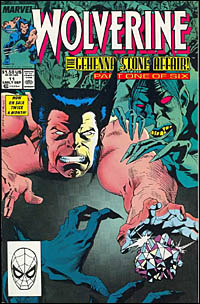

I was pretty thrown by the beginning of the movie, when the Rolling Stones are playing on the soundtrack, Jack Nicholson (as Costello) is doing a voiceover talking about Kennedy, and all the cars look ancient. All signs point to this as Wonder Years territory. Here we meet the Matt Damon character as a kid. It's his first encounter with Costello. Costello asks, "You like comic books?" And the comic book he gives him... is Wolverine #11, dated Early September 1989 (meaning it came out in mid-summer). Then we jump to "the present." Now, the movie is packed solid with cell phones. It's practically a Sprint commercial. So let's go ahead and say that the present is 2006, the year the movie was released. Add 17 years to the earlier scene and that puts the Damon character in his mid- to late 20s. That seems about right, for the character. (Let's forget for a moment that Damon is actually pushing 40 and was in college when Wolverine #11 came out.) So if this first scene is supposed to take place in 1989, why all the misdirection? Why not some era-appropriate cars? You want to signal '89, you don't put the damn Stones on the soundtrack. You put on Fine Young Cannibals, or Milli Vanilli. Or hey, New Kids on the Block! Might've been able to have Marky Mark call in a connection there.

Return to the Calendar page! |