All Roads

Premise

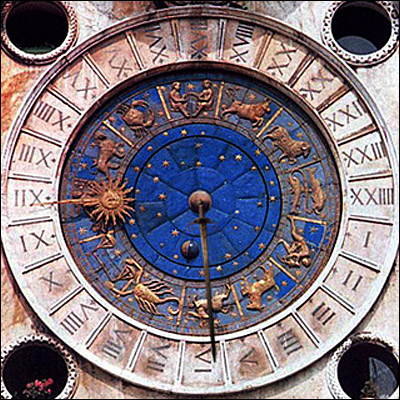

Spoilers Good copyediting also sends the message that the work at least aspires to a standard of professionalism. Poor copyediting signals that it's amateur hour. This isn't necessarily a huge problem if you're aiming low, but All Roads isn't You Are a Chef! — it depends on atmosphere, on successfully evoking high intrigue in Renaissance Venice. But the language errors puncture that atmosphere. You can't paint the Mona Lisa on the back of a paper plate. Of course, saying that assumes that you otherwise would have had the Mona Lisa to begin with, and even with perfectly edited prose, All Roads would have fallen short of the richness to which it aspires. This time around I played it with Elizabeth, and she was the one who chose most of the commands. She soon found that examining the items mentioned in the descriptions tended to be fruitless. "Every time we look at the art it just says that it's beautiful," she complained at one point. "It's like the time I asked for more details about an apartment and the landlady emailed back, 'It is very nice.'" So why were we playing it in the first place? For my part, it was because I had just finished watching Memento again, to which All Roads drew many comparisons back in '01. Or, rather, it drew comparisons to Memento by the few people who figured it out. For unlike Memento, which explains most of its gimmick right up front — ie, that we are watching the events of Leonard Shelby's life in reverse chronological order, in large part in order to mimic the fact that he doesn't remember what he's just done — All Roads attempts to draw out the mystery right up to the end. The problem is that very frequently it draws out the mystery past the end. I certainly had only the faintest idea what had happened the first time I played, and from the reviews I have gathered that I was far from alone. Many reviewers have also complained that All Roads is "on rails" — that is, that you can't really affect the plot and generally can't do anything useful other than the one thing the author wants you to do. This didn't bother me at all. I firmly believe that requiring the player to explicitly enter commands automatically makes interactive fiction a fundamentally different medium from straight prose. In fact, I would put forward the opposite idea: All Roads falls down in offering the player too much freedom, namely, the freedom not to pick up all the clues. See, in a puzzle game, if you miss a clue and therefore botch the puzzle, you are left with a story that culminates in disaster. Take Trinity, for example. You play an American tourist visiting the Kensington Gardens in London when nuclear war breaks out; your goal is to escape before the first missile strikes. To do so, you must cross a lawn, but if you try, the grass springs to life and forces you back onto the walkway. And so, caught in an atomic blast, you die. Well then! Clearly that's not the optimal ending. So what do you do? You fire up the program again and carefully look for clues. Aha! You see some bicyclists crossing the lawn with no trouble! This tells you that you'll have to find some sort of wheeled transport, and with this clue, you're able to continue. (At least, that's the theory. I actually never noticed that clue and spent an entire year unable to complete the prologue. Thank heaven for hint books.) But now let's consider All Roads, and this is where the spoilers really kick in. In All Roads, you play the disembodied intelligence of the late William DeLosa. You don't know that you're a disembodied intelligence, though, nor do you know that you're dead. You think you can teleport. What you can actually do is travel in time, and so the story proceeds out of chronological order, with the protagonist trying to figure out where he is and what he's doing, as in Memento. All Roads adds the additional question of whom William is inhabiting, since at different times he finds himself in the body of his brother Sebastian and in that of a man Sebastian means to kill. And the only reason I knew any of this after playing All Roads twice is that I read this post by Carl Muckenhoupt. An interactive piece like All Roads, in which the main puzzle is simply to figure out what's going on, differs from a more conventional text adventure in a crucial way. Unlike in a puzzle game, players who miss the clues aren't prevented from reaching the optimal ending, since there's only one ending to reach. The problem is, they haven't read the optimal story. In All Roads, for instance, you have to enter a church, and if you choose to pray, you learn that you think your name is W. DeLosa. But you don't have to pray, and if you don't, then the introduction of William DeLosa at the end comes completely out of nowhere! There is also an appointment book. If you sign it, then read it, then sign it again, then read it again, you will finally discover that now you think your name is S. DeLosa. But you don't have to do that, and if you don't, this crucial plot point is not part of the story you read! So you get to the end having read a story containing only a fraction of the material you need to understand it. And since there's nothing other than your own confusion to indicate that you've missed the boat, or that there's even a boat to have missed, all the author has done by giving you this freedom to act is given you the freedom to read a worse story than you otherwise might. And what's the point of that? Postscript: I just played through All Roads again, after writing all this and rereading Carl's post, and I still don't entirely get it. I finally do get the business with the ring — until about sixty seconds ago I thought that William's powers were somehow connected to the ring, and hadn't twigged to the fact that the "thievery" for which Giuseppe is hanged is thievery of the ring. Meanwhile, I've given up on following the conversation between the Denizen and Giuseppe... so he's a member of the Resistance? Holding a post in the government? But he's actually loyal to the government? Except the Denizen is the government, but is also a member of the Resistance, so his loyalty is actually disloyalty? Or... oh, forget it. I suppose that one thing All Roads has going for it is that it's so confusing that many players probably do realize they've missed a lot and go back looking for clues. But even with seven years' worth of hints to work with, I still found that when the game told me I was starting to get a headache, it produced the wrong kind of empathy.

Return to the Calendar page! |