Nineteen Eighty-Four

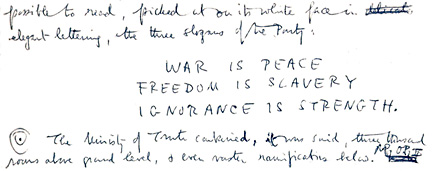

Premise Winston Smith works for the Ministry of Truth. His job is to falsify the records of the past to reflect the Party's wishes, wishes that change from moment to moment. Winston finds himself increasingly troubled by the infinitely malleable memories of those around him — they seem genuinely to remember the things he has made up. They seem genuinely to remember the things they have made up! Winston has heard that there is a resistance movement — its purported leaders, captured by the secret police, regularly appear on the telescreens to confess their crimes prior to execution — but doesn't know how to go about joining it. Then, one day, he receives a note...

Duran Duran Think about your favorite songs. Most of them, I imagine, are by bands you like. Anyone who's been to this site knows that my favorite song is "Smells Like Teen Spirit," but I could name literally dozens of other Nirvana songs I really enjoy. But this isn't always the case. Back before the advent of the web I bought many a CD just because I liked the one song on it that I'd heard, only to discover that the rest of the album sounded nothing like it. This sort of thing is not uncommon. I remember reading a review of a Primitive Radio Gods concert that said, "Stay away! The rest of their stuff is nothing like 'Phone Booth'!" And then you have the Green Day song from with the acoustic guitar and orchestral strings that started popping up in 1998 on soft-rock stations in between Air Supply and the Gin Blossoms. I wonder how many receptionists heard it at work, stopped by the Sam Goody, picked up a copy of Nimrod, listened to "Platypus," and cried their eyes out. I thought Nineteen Eighty-Four was like that. There are authors who, when they appear on syllabi, might have any number of their titles appear next to their names — take an American lit class and there's no telling which Faulkner novel you'll get. But with some, well, once you see the name, you know what you're getting. When you see Fitzgerald, you know you're probably not getting The Last Tycoon. And when you see Orwell, the chances are mighty slim that it's going to be anything he wrote in the 30s. Going into my reread of Nineteen Eighty-Four, I assumed this was because in the 40s he basically started a whole new career writing polemics against Stalinism. In the music analogy, he'd be a band that changed its sound and suddenly became a lot more successful. Only this isn't true at all! Here I'd thought I would find a radical departure from his reportorial novels on poverty in Britain. Instead I found... a reportorial novel on poverty in Britain! Everyone remembers Newspeak and Eurasia and Eastasia and Big Brother and telescreens and Room 101. But Parts One and Two are more about "coarse soap and blunt razor blades." Like Down and Out in Paris and London, they're about the "effort to escape the vile wind," about standing in line for "the regulation lunch," about carefully, obsessively, parceling out pieces of cigarettes to oneself. Like A Clergyman's Daughter, they're about lives whose potential leisure time has been swallowed by obligatory volunteer work. Like Keep the Aspidistra Flying, they're about boarding houses "that smelt always of cabbage and bad lavatories," about wan city dwellers blinking in the sunlit countryside, about a couple trained to be celibate awkwardly trying to find a spot among the trees for furtive sex. Like The Road to Wigan Pier, they're about cities full of proletarian women "blown up to monstrous dimensions by childbearing, then hardened" who live in houses where every time the residents think they've beaten back the bugs, they turn to find them "massing for the counter-attack." And like Coming Up for Air, they're about the hopeless quest to return to the Golden Country in an England where bombs are falling. Orwell simply had to move his revolution from 1940 to 1950. As for The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism... I've read only a tiny fraction of Orwell's essays, but I think I've found most of the precursors. For instance, I read an essay that argued that the nature of atomic weapons pointed to "an epoch as horribly stable as the slave empires of antiquity" in which "three super-states" would come to dominate. All of which leads to the inevitable question: What the hell does any of this have to do with Duran Duran? As noted, I was completely wrong to think that Nineteen Eighty-Four was so different from the rest of Orwell's work that I'd end up scratching my head wondering where it came from. Quite the opposite turned out to be the case — the family resemblance to its predecessors could hardly be more striking. And yet Nineteen Eighty-Four is so much better! A few paragraphs ago I talked about how sometimes you like a song, but it's really just first among equals in the band's catalogue. For instance, one of my favorite bands is called Scarling. Looking at the September 2007 edition of my list of favorite songs, I see that my favorite Scarling song, "Can't," checks in at #6. Other Scarling songs appear at #15, #17, #29, #72, and #87. (This list is currently undergoing revision, but those songs will all be sticking around.) Now, another one of my favorite songs is "Union of the Snake" by Duran Duran. It's #16 on this list. Other Duran Duran songs on the list are... oh, there aren't any. Nor do I even own any. Does that mean that "Union of the Snake" is like the Primitive Radio Gods and Green Day songs mentioned earlier, totally unrepresentative of the band's usual output? Not at all! "Union of the Snake" actually sounds extremely similar to "The Reflex" and "New Moon on Monday" and all the rest of the Duran Duran canon. I find the others pleasant enough when they pop up on the radio. So why don't I get them? Because any time I felt like listening to Duran Duran, the song I would choose would inevitably be "Union of the Snake." So the others would just be taking up hard drive space. This is sort of how I feel about Nineteen Eighty-Four. I can see how great a debt it owes to Orwell's novels of the 1930s. But I also feel that it kind of makes those novels obsolete. So this is my verdict at the end of my Orwell project: if anyone ever asks me what Orwell books I'd recommend, I will ask, "Have you read Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four?" And if the answer is yes, my reply will be, "Okay, then you're covered."

I wish they all could be dystopian girls

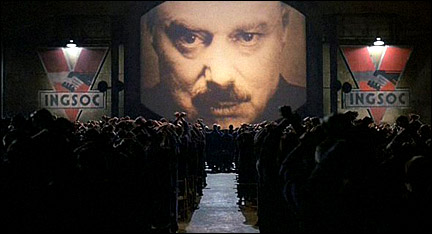

Nineteen Eighty-Four I also rewatched the movie adaptation of the novel made in 1984 — filmed, I have read, on the very calendar dates specified in the novel. It is an extremely faithful adaptation, so faithful that I have little to say about it. What what little I do have to say is positive. When you're adapting a story everyone already knows, good casting becomes paramount, and the casting here is spot-on perfect. In preparing to write this article I looked at a lot of other adaptations of Nineteen Eighty-Four — paintings and comics and things — and they were just wrong. If Winston Smith doesn't look like John Hurt, then it's just not Winston Smith. Likewise, after watching this movie for the first time back in the 80s, I could no longer accept an O'Brien who looks very different from Richard Burton, nor a Julia who differs substantially in appearance from Suzanna Hamilton. The sets are also great. One of the key observations of the novel is that, compared to the average middle-class reader of 1949, the most powerful oligarchs in Oceania live very poorly; the privileges they enjoy amount to a cup of coffee in the morning and the ability to turn off the TV for a few minutes. The movie gets this across beautifully without drawing too much attention to it. O'Brien's quarters are virtually bare, but he has a desk and his floor isn't crumbling, and very few others can say the same.

Return to the Calendar page! |