Masterchef Australia

Masterchef Australia

Fremantle Media Australia, 2009–

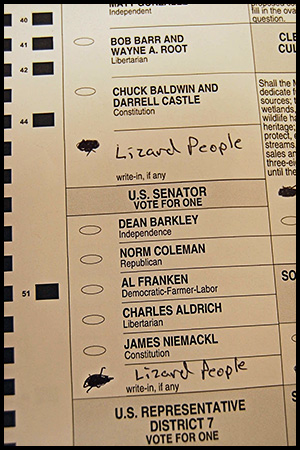

Last November I found it difficult to do much more than listlessly watch Youtube videos, partly because my bad kidney was flaring up pretty severely and partly because on Election Day the winning ballots looked like this:

Before the election I had once pulled up a Gordon Ramsay video recipe—gnocchi with peas and parmesan, if you’re keeping score—and Youtube therefore decided that I might be interested in an episode of a cooking competition called Masterchef, which Ramsay hosts. I watched it, but I didn’t much care for it. There were three judges, which according to the American Idol formula means that one of them will be the nice one, one will be the asshole, and one will be the level‐headed one maintaining the balance between the other two. The problem is that Gordon Ramsay’s schtick is to taste a plate of food and shout, “What the fuck is this shit, you fucking donkey?”—but since he’s the primary host, he was slotted as the center guy. The producers brought in someone even more assholish to be the asshole judge, a dour bald guy with a penchant for sneering at the dishes and scraping them into the trash before the teary eyes of the contestants. I was going so say that it made the show joyless, but it’s more than that: it seemed like the premise was “Cook food in an abusive household! Win $250,000, all of which you will have to spend on therapy!” As it turned out, though, even had I been inclined to watch the next episode, I couldn’t: copyright issues meant that only a handful of Masterchef episodes were up on Youtube. What were available, and what Youtube served me up next, were the most recent two seasons of Masterchef Canada. So I watched a couple of episodes of that. The judges were much more polite. (Well, there were two polite judges and one loud, flamboyant judge with blue hair and a thick Hong Kong accent. But even he was friendly enough.) I also took a liking to one of the third‐season contestants, Mary: she was cheerful and winsome, with big green glasses and a Molly Mockery haircut, and on top of all that was a vegetarian — and now that I’ve seen several hundred Australian and Canadian Masterchef contestants come and go, she remains the only vegetarian I’ve seen make it out of the qualifying rounds. I figured I would stick with Masterchef Canada until Mary got the boot, and then switch to cat videos or something. But Mary won the damn thing! I wound up watching the entire season! Then I watched season two. At which point I could post this to Facebook:

But then for some reason instead of jumping back again and watching season one, I thought I’d try a different country. Pretty much on a whim I typed in “masterchef australia” to see whether there was such a thing. It turned out that there was. The first result to come up was the season three premiere, and since season three of Masterchef Canada had treated me pretty well, I decided to start there on the Australian version. It soon became clear that this show was a bigger deal than its Canadian counterpart: fifty contestants instead of twelve, cooking in a UNESCO World Heritage Site instead of in a little TV studio, with helicopters dropping off ingredients… and yet somehow it wasn’t until several episodes in that I did some poking around and discovered that the format of the show was equally gargantuan. Each season of Masterchef Canada was 15 episodes long, and I plowed through two seasons in five days. The season of Masterchef Australia I had just embarked upon consisted of 86 installments. Eighty‐six! Many of them running for well over an hour! And then it wasn’t until several episodes after that discovery that I did some more poking around and learned that the American version, the Canadian version, and 48 other editions of the program owe their existence to Masterchef Australia. The British version came first, and has done well enough to run off and on, mostly on, since 1990. But what spawned the dozens of copycats was when Australia’s Network Ten launched its local adaptation in 2009 and struck gold. The show was a massive success. One of the prizes offered in the first season was a cookbook publishing deal; that prize went to winner Julie Goodwin, who became the bestselling Australian author of 2010. Season two was an even bigger phenomenon than season one: when contestants lost unexpectedly it was headline news, and the finale became the single most watched program other than sporting events in the history of Australian television. Some contestants landed their own cooking shows. Others became tabloid fodder, their love lives dissected by millions of strangers for weeks on end. Ratings are no longer quite so high now that eight seasons have aired; it looks like last year Masterchef Australia came in fourth (again, excluding sporting events), and the network has scaled the show back accordingly. But that means that the most recent season consisted of a mere sixty‐three episodes. (The upcoming season of Masterchef Canada? Twelve.)

I have way too many notes to be able to shape them into a coherent article in a reasonable amount of time, so I’m just going to bang this out minutiae‐style and we’ll see how it goes. My time starts now!

- Again, I watched Masterchef Canada before I switched

over to the Australian version, so let me start by describing the format

of the Canadian version.

People send in audition tapes, and forty of them are selected to come

audition in person.

Each of these forty contestants cooks her signature dish for the judges,

and fourteen are selected to advance to the main competition.

There are four phases to the competition.

The first phase is the mystery box.

Mystery boxes usually contain an odd assortment of ingredients; one box

contained ground beef, arctic char, pickerel, littleneck clams, red

potatoes, brussels sprouts, summer squash, carrots, tomatoes, blueberries,

wild rice, green lentils, wine, and rum.

Using at least one of those ingredients, plus a pantry of staples (flour,

milk, eggs, that sort of thing), contestants compete to see who can create

the most delicious dish.

The winner gets to select the core ingredient for the second phase of the

competition: the invention test.

Say it’s pork.

Contestants have to come up with a dish that not only includes that

ingredient but makes it the “hero of the dish”, with the help

of a much more expansive pantry.

Various restrictions might be imposed: contestants might be required to

cook Mexican food, or the pantry might only contain foods whose names

begin with vowels.

Time limits are always quite tight—an hour, perhaps.

The cook whose dish is judged to be the worst is sent home.

End of episode!

Time limits are always quite tight—an hour, perhaps.

The cook whose dish is judged to be the worst is sent home.

End of episode!

The next episode consists of phases three and four. Phase three is an off‐site team challenge. The two winners of the invention test are the captains, and after each one has chosen the members of her team, the two teams might each be given a stall at a farmers’ market and $500 to spend buying ingredients from the vendors to turn into complete dishes, with victory awarded to the team that makes the most profit. Or perhaps they have to make hors d’oeuvres at a fashion show, and the guests cast ballots to determine the winning team. The losers then enter phase four, the pressure test. No creativity required, for once: in the pressure test, contestants must do the best rendition they can of the dish presented to them. Once again, the worst dish sends its maker home. Put it all together, and here’s the arithmetic: two episodes winnowing the contestants down to fourteen, plus thirteen episodes in which one person goes home at the end, equals the fifteen episodes I mentioned above. The math for the Australian version is rather different.

One of the things that most fascinated me about Masterchef Australia was the way the producers constantly tinkered with the format, trying out new types of segments to add interest, and ditching old segments that weren’t working. It was a sort of optimization puzzle playing out at the same time as the cooking competitions. In the early seasons, about which I’ll have a lot more to say in a bit, you never really had any earthly idea what you might get in a given episode. But things have settled down in the past three seasons, so while there’s still a fair bit of variation from week to week, a typical sequence goes something like this. Again, it starts with a mystery box: contestants make the best dish they can out of an odd assortment of ingredients, and the judges taste a few they like the looks of. (The fact that the judges only sample three or five dishes means that the cutaways are basically a cavalcade of attractive women breathlessly exclaiming about how much they want to be tasted. “I’ve only been tasted twice, so I’m dying to be tasted again! It’s not fair—Sarah gets tasted every week!”) The judges then declare a winner, who gets to set the parameters of the invention test. But at the end of the invention test, no one is sent home. The three contestants judged to have made the best dishes are selected as winners; the three (or, often, four) whose dishes are tactfully deemed the “least impressive” are sent to a pressure test. The pressure test is an episode unto itself, and at the end of it, someone is sent home. Episode three of the week is the immunity challenge, in which the three winners compete to have the chance to square off against a professional chef. The prize for victory, which is rare, is an immunity pin, which allows the recipient to save herself from the elimination round of her choice. The fourth episode of the week is a team challenge, which also gobbles up the entire hour (or more!). The fifth episode sees the members of the losing team compete in an elimination, often in multiple rounds, at the end of which someone goes home. And then there’s a sixth episode, the master class, in which the contestants can finally relax and learn new cooking techniques from the judges and a variety of guest chefs. So, with a number of episodes at the beginning of the season to set the year’s cast of 24 competitors, followed by nine weeks as a daily rather than weekly show just to whittle that group down to six finalists, plus various twists like eliminated contestants cooking their way back in and theme weeks with only one elimination, you can see how the Australian version of the show looks like the Mahabharata compared to the other national editions, which are more like haikus.

- Because commuting back and forth between Perth and Sydney six days

a week would be a bit of an ask, contestants are sequestered for the

duration of their stay in the competition: no phone, no Internet, no

going for a walk.

From what I’ve read, not every country’s version of the

show does this, and those that do tend to sequester contestants in a

hotel.

But Masterchef Australia puts the contestants up in a

sprawling vacation home.

When all 24 are still in the running,

they’re crammed in there Tetris‐style, but by the end

it’s just a handful of souls rattling around.

In the Canadian edition we never see any of this, but on Masterchef

Australia it’s part of the show: we see the contestants wake

up and put on their makeup and work out in the home gym and make some

breakfast before being chauffeured to the studio.

I love the bits at the house—I wish there were more.

In interviews contestants have said that, being in a competition against

a bunch of amazing cooks and with a quarter of a million dollars on the

line, they spend all their time studying: the house is packed with

cookbooks, and prerecorded cooking shows are constantly playing on the

TV (except for the one hour a week when they watch Game of

Thrones).

There have been references to contestants messing up an element of a

dish (e.g., choux pastry)

during a televised segment and then practicing it at home, off camera,

eight or ten or twelve times until they get it right.

That might be interesting to see!

during a televised segment and then practicing it at home, off camera,

eight or ten or twelve times until they get it right.

That might be interesting to see!

- Some contestants can’t handle the sequester.

In season one, one dropped out saying that he missed his wife too

much, and in season two, two dropped out saying that they couldn’t

stand to be away from their kids.

In the most recent season, another mother of young children had a minor

breakdown and spent a whole day “cooking for her

kids”—and you know those moms whose idea of cooking for

kids involves “hiding vegetables” in other foods and adorning

them with silly faces made out of sauce?

She was one of those.

It turns out that chefs with three Michelin stars don’t like that.

- As noted, the first season of Masterchef Australia I

watched was season three, after the most egregious errors in the original

concept had been corrected.

So it was very interesting to go back to season one and discover just how

misconceived some of the original parameters were.

For starters: in season one, after a team challenge, everyone on the

losing team voted someone off.

The host—for in the first season, and only in the

first season, there was an actual host in addition to the three

judges—even suggested that contestants might want to vote

off the strongest cooks, to clear the field for themselves.

This is obviously inimical to the goal of identifying the best amateur

cook in Australia.

That the show was originally intended to revolve around a combination of

cooking and social engineering was clear from the way the editors built

storylines around conflict within the house.

The friendship among three contestants in their early twenties was cast

as an in‐game “alliance” called “the kiddie

mafia”, and other contestants were filmed grumbling about how

annoying those kids were.

It was clear that “these people are all living on top of each other

and getting on each other’s nerves” was intended to be a

running theme, and a big part of the reason the house was made part of

the show.

The producers also tried to jumpstart some rivalries during the cooking

segments, having the judges ask contestants to weigh in on the appearance

of each other’s dishes and suchlike.

But this all turned out to be an exercise in tugging the program in a

direction it just didn’t want to go.

The contestants didn’t turn on each other out of

claustrophobia—in most seasons, they became a surrogate

family.

Even in the first season, as the weeks went on, the contestants complained

more and more vociferously about how much it sucked to have to vote out

someone they cared for.

So from season two on, the producers have been increasingly committed to

the principle that Masterchef Australia is a cooking show,

not a social engineering show, and when you are eliminated it’s

because you cooked the worst, not because you made the wrong friends.

- I say “increasingly” because this shift didn’t

happen all at once.

Even after voting each other off the show was, thankfully, a thing of the

past, for a few additional seasons contestants could be eliminated from

the competition without making a bad dish: they might fail to identify

enough ingredients in a particular cake, for instance, or give the wrong

name of an herb (or, as the Australians say, “a herb”).

And the social engineering aspect of the show persisted for a while in

an attenuated form, as for at least a couple of additional seasons the

members of a losing team were sometimes asked to deliberate amongst

themselves and decide which two of of their number would go into a

head‐to‐head elimination.

But both of those elements are now completely gone.

In fact, I would argue that these days the elimination of the social

aspect of the competition may have gone too far!

Contestants never pick their own teams anymore: one of the judges will

either divide the crowd of contestants in half, or go

“one‐two‐one‐two”, or have them draw

lots.

I guess someone decided that selecting captains and having them choose

up sides was cruel to the people who got chosen last, and that could no

longer be borne.

(The judges were never remotely as cruel as the judges on the American

Masterchef, but in the first few seasons, the woman who

cooked the calamitous preschool dish would have been scolded or snarked

at.

In season eight?

It was a lot of gentle talk that “we love how much your heart is

with your kids, but you need to decide whether you want to be

here…”)

And I certainly can’t fault the producers for trying to minimize

cruelty!

But seeing who would choose whom for a team challenge was always

interesting.

I miss it.

And I certainly can’t fault the producers for trying to minimize

cruelty!

But seeing who would choose whom for a team challenge was always

interesting.

I miss it.

- Another huge mistake in season one: defeating a celebrity chef

automatically advanced a contestant to the final week.

Sounds good, right?

But think about it.

Here you’ve got these people who’ve given up their jobs,

left their families, in multiple cases even put their honeymoons on

hold for the chance to be on this TV show.

When they lose an elimination round, their punishment is that they are

removed from the TV show.

And in season one, two of the contestants did outscore a celebrity chef,

and their reward was… to be removed from the TV show!

While waiting for finals week to roll around, they missed the exposure

of being on TV, missed all the exciting field trips to cook in exotic

locales, missed most of the master classes to learn new techniques, and

missed the daily competitions to keep their

Masterchef‐specific skills sharp.

So it’s no surprise that when the final week began, the two people

who’d skipped ahead to that point were the first two

eliminated.

It was interesting to see that it took a disaster of that magnitude for

the producers to come up with the idea of awarding an immunity pin

instead.

- The immunity challenges are where the producers’ constant

tweaking of the show has been most on display.

Initially the rules were simple: whoever won the invention test

got to face off against a celebrity chef.

The chef brought in one of her signature dishes, had the contestant taste

it, gave the contestant a recipe, and the judges retired to the back

room while the contestant and the chef each made a rendition of the

dish.

The judges then allocated up to ten points apiece for each dish, not

knowing who made which.

On the rare occasions that the chef failed to outscore the contestant, the

contestant won an immunity pin.

But in season four, the winner of the invention test faced off against a

trio of chefs, and was able to call two fellow contestants down from the

balcony to help out—thus putting the spotlight in the

immunity episodes on more than one contestant.

It went to show how far the show had come from season one’s abortive

attempts to encourage skullduggery: even though the helpers were actually

hurting their own cause by giving a competitor an advantage, there was no

thought of deliberately cooking a bad dish to keep the immunity pin out of

play.

They helped because they’d become close friends.

Each team made three courses of their own devising using a core ingredient

of the guest chef’s choice, and instead of giving a score, the

judges declared a victor of each course; if the contestants won more

courses, the captain received a pin.

In season five—the bad season, as future items will

illustrate further—there weren’t many immunity

challenges and they were all in hinky formats (e.g., select ingredients

in the dark).

Then in season six came the new format: three winners of the

invention test were declared each cycle, and all three advanced to the

first round of the immunity challenge, at which point they would

compete in a mini‐challenge before the winner of the

mini‐challenge faced the celebrity chef.

Rather than choosing a single core ingredient and having access to a full

pantry, in this new format the chef chose between two copious but limited

benches of ingredients, and it was back to points scored on a single

dish.

In season seven, the contestant who won the first round picked which set

of ingredients to share with the celebrity chef.

In season eight, the celebrity chef had to hide in a closet while the

first‐round winner got a head start on the second round.

So much tinkering!

And I haven’t even mentioned all the season‐long mentors

and guest judges and whatnot who’ve been shuttled in and out as

the producers have played around with the format.

- Not only did letting three contestants rather than just one into the

immunity challenge keep an entire episode’s spotlight off one

person, it also meant that the chance at immunity no longer came down to

a single judgment call in the invention test.

Which brings me to another twist in the first season that looks like a

crazy error of judgment in retrospect: once the field had been narrowed

down to seven, the three judges just decided of their own volition to

bring three eliminated contestants of their choice back into the

competition—one of whom came very close to winning the

whole thing at the end.

I understand the panic that let to this decision: a lot of the strongest

contestants had been sent home, some for reasons such as

“misidentified farro as barley”, and it therefore looked like

the big prize might go to someone who the producers, the judges, and the

audience all knew was far from the best amateur cook in Australia.

At the same time, to retroactively turn three arbitrarily selected

contestants’ eliminations into prizes—after all, in

season one skipping weeks of competition was the reward for winning

the celebrity chef challenges!—was not particularly fair to

those who had survived into the top seven.

In season two, the eliminated contestants at least had to cook their way

back in, but the contestants who thought they’d made the top seven

were understandably irked when three people they’d defeated were

let back in.

This move was so unpopular that in seasons three and four, this element of

the show was scrapped.

Single elimination, no do‐overs (except in the case when one

contestant was discovered to have cheated).

In seasons five through eight, however, the producers have settled on a

compromise: around the time the field has been whittled down to the top

ten or so, the eliminated contestants cook off against each other for a

chance to return, and one is let back in.

In seasons six and eight, I was very happy to see a couple of my favorite

contestants return, so I’m not going to complain.

But it does seem like it might be fairer to just make this a double

elimination competition.

- Of course, that raises the question of whether fairness is the

point.

I’ve written in the past about how sports leagues tend to put a

thumb on the scale to prevent the trophies from going to the best

teams.

Consider the NCAA basketball tournament.

Teams play for several months to demonstrate how good they are over a

sample size of 30+ games… and then whether

they advance in the tournament is determined by a sample size of one

game.

The whole point of playoffs is to lower that sample size, let volatility

play a bigger role in determining the results, and increase the likelihood

of upsets.

And yes, it’s exciting when George Mason knocks off UConn or

Northern Iowa shocks Kansas.

But it does mean that you frequently have something like the

20th‐best team in the country cutting down

the nets at the end.

And on Masterchef Australia, there have been seasons when

the frontrunner was knocked out before her time.

In season four, Mindy was a heavy favorite, but a single slip near the

end, when the safety nets had been removed, left her in fourth.

Even more shockingly, in season two, Marion was pretty much universally

considered the best cook, but she ended up in an elimination due to her

teammates’ missteps, and a close judgment call about a satay sauce

sent her home in ninth place.

Reported nine.com.au, “the country lit up with cries of horrified

disbelief”.

Of course, the real prize in Masterchef is the career

opportunities it provides, and Marion is now a big TV star in Australia

and makes millions from her line of Asian food kits.

So there have been worse injustices.

Of course, the real prize in Masterchef is the career

opportunities it provides, and Marion is now a big TV star in Australia

and makes millions from her line of Asian food kits.

So there have been worse injustices.

- Among those worse injustices would be “pretty much anything

involving real life rather than a TV show”.

I spent a lot of the previous item talking about sports.

I do not currently follow sports.

Every so often I make an effort to give them up, and at the moment it has

been the better part of a year since the last time I went to the ESPN

web site.

Watching sports is a mechanism to elicit feelings of elation and

despondency in response to competitions that, unlike wars or elections,

have no practical effect on the lives of the spectators.

Not liking to be upset over something that doesn’t matter is one of

the reasons I keep giving up sports.

And yet many times while watching Masterchef Australia I

found myself thinking that, yeah, this is just a sports substitute.

When one of my favorite contestants would squeak out an unlikely victory,

I would cheer and applaud alone in my apartment like an idiot.

When one of my favorite contestants lost, I would mope about it.

I.e., I would mope about an episode of a TV show, that had first aired

years earlier, on a continent on the other side of the largest ocean in

the world.

- Another reason I keep giving up sports is that I hate the extent to

which the outcome of a game is in the hands of the referees.

One of the magic tricks that Masterchef Australia pulls off

is the way the judges somehow make their decisions come off as fairly

objective even in cases when they couldn’t ever really be.

Things like “this pork is raw” are indisputable, but the

judges have a knack for making arbitrary decisions sound like the

inevitable results of a formula:

- “Bruce, your sauce was too salty, and Sheila, your dish just

didn’t have enough sauce, but Matilda, even though your sauce

tasted the best, it had no discernible orange flavor, and this was

supposed to be duck à l’orange, so we’re sorry, but

you’re going home.”

- “Sheila, your sauce was decent, but there wasn’t enough of

it. Matilda, your sauce was delicious, but it didn’t showcase

the orange the way it was supposed to. But at the end of the day,

flavor is the most important thing, so you two are safe; Bruce, your sauce

was too salty, and it ruined the dish, so you’re going home.”

- “Matilda, your sauce could have used a lot more orange, and Bruce, your sauce could have used a lot less salt. But at least you both offered us something to tie the dish together. Sheila, your sauce was almost nonexistent, and for that reason, we’re sorry to say you’re going home.”

- “Bruce, your sauce was too salty, and Sheila, your dish just

didn’t have enough sauce, but Matilda, even though your sauce

tasted the best, it had no discernible orange flavor, and this was

supposed to be duck à l’orange, so we’re sorry, but

you’re going home.”

- And speaking of the judges, I suppose that I should finally actually

talk about them—the three constants on the show as contestants

have come and gone and rules have done the same.

So constant are they that eight years have passed and they even stand in

the same places most of the time.

On the left is chef Gary Mehigan.

He’s the dad.

Usually he’s the friendly dad, sometimes he’s the stern dad,

but that’s his role.

On the right is food critic Matt Preston, an affably pretentious

dandy.

He’s this big guy who bears a striking resemblance to Fred

Flintstone and invariably wears a

cravat

with matching pocket square, usually in tandem with an equally garish

suit.

In the middle is George Calombaris, another chef—and the

one native Australian in the group, as Matt and Gary are both from

Britain.

George is a little bald fireplug of a guy who’s the bloke of the

group, with his broad accent and clichéd tough‐love speeches,

and simultaneously its leading exponent of froufrou modern cuisine,

delivering paeans to the value of “negative space” and

carefully moving microherbs around the plate with tweezers.

I can’t say that I ever fired up an episode in order to watch the

judges, but they’re a jovial crew with a chemistry that the North

American judging panels lacked, and they made the Australian show feel

like home to me.

- Of course, Australia is not home to me.

Though, as

Pattern 23

points out, it’s not too far off compared to a country like

Britain.

Consider this climate analogy map of Australia I found:

There’s a whole lot of California on there, especially in the places where people live. I remember that when an Australian friend came to visit back in the ifMUD days, he remarked that his fifteen‐hour plane ride had taken him from a place that was warm and dry and full of gum trees to a place that was warm and dry and full of gum trees. Which isn’t to say that there are no differences. For instance, looking at the map above it’s kind of hard to miss that the climatic belts are upside down. In season eight, when one team had to cook using only ingredients from “the north”, that meant the tropics—they were given bananas and dragonfruit and coconuts and things. Whereas the table of ingredients from “the south” included pears and blackberries and kale and other cool‐weather produce from Australia’s lone cool‐weather state, Tasmania. I was surprised to find that it didn’t take me any time to internalize this. But I guess it makes sense. I don’t do well with narrative driving directions—I need a map. Like, I actually need to be able to visualize where I am on the earth’s surface in order to get from Point A to Point B, and while in transit I use the sun to orient myself. So, watching this show, I sort of mentally placed myself where the camera was, and so it was only natural for north to be the hot direction, because I could feel that that was where the sun was!

- On the other hand, the way the seasons are flipped around was

something I never got used to.

I think the fact that this is a food show made it particularly hard,

because a lot of what I eat carries a date stamp.

The last week of May means Earliglo nectarines; the second week of June

is when the Index cherries run out; dry‐farmed Early Girl tomatoes

show up in mid‐August; there are still a few last plums left in

the third week of October, even though I don’t like plums; and who

cares about December and January and February?

That’s when you go to Trader Joe’s because all you can get at

the farmers’ markets are parsnips.

For a long time the Romans didn’t even bother to divide winter into

months, because from an agricultural standpoint there was no difference

between one winter day and the next.

So it’s weird to hear the months named after goddesses and emperors

dismissed as the unimportant months when you might as well stay in and

make a chocolate dessert because nothing’s growing, and to see the

afterthought months be the ones with a bunch of dates circled in

foodies’ calendars.

(And apparently I’m not the only one who finds this a difficult

adjustment—I had to shake my head when I played

Europa

Universalis IV

and discovered that it had the Southern Hemisphere suffering from

snowstorms in February.)

Europa

Universalis IV

and discovered that it had the Southern Hemisphere suffering from

snowstorms in February.)

- One of the weirdest effects of the seasons being flipped around is

that when contestants have to cook to a Christmas theme, as has happened

in multiple seasons, they’ve been pulled in two very different

directions.

Like the U.S., Australia began as a British colony, but the first

fleetload of prisoners didn’t arrive at Botany Bay until the U.S.

was already independent.

Australia remained a dependency of Britain into the

20th century, and

in some respects it still isn’t fully independent: it has the Union

Jack on its flag and the Queen of England on its money.

It also has a huge population of British ex‐pats (Gary Mehigan and

Matt Preston among them).

So embedded in Australia’s cultural DNA is the idea that Christmas

means dried fruits and peppermint and warming spices.

But geography says that it’s scorching hot out—my one

trip to Australia lasted from a December 20

to a December 26, and you could basically

jump up and high‐five the sun.

“You don’t want a hot dessert at Christmas—you

want something nice and cold!” one competitor explained.

And so they ended up making things like ice cream and pavlovas with

fresh berries and kiwi fruit, and got dinged for omitting the brandy and

eggnog.

- I didn’t know what a pavlova was before I watched

Masterchef Australia, but I learned very

quickly—apparently in Australia it is the archetypal

dessert, like chocolate chip cookies in the U.S.

(A pavlova turns out to be a sort of cake made of two textures of

meringue, topped with fruit.)

Which raises the question of what constitutes Australian food.

Actually, it was always oddly uncanny for me when a team on

Masterchef Australia would be tasked with cooking

“American food”—a label I tend to use to mean

“it isn’t anything in particular”.

What would the contestants find distinctive about it?

Apparently in Australia “American food” signifies what those

of us who live here would call “Southern food”: grits,

cornbread, fried everything, desserts explicitly designed to be served to

Elvis Presley in 1977.

Whereas to me eating in the U.S. is an exercise not in regionalism but in

globalism.

Eating a pizza margherita on Monday, a honey‐curry burrito on

Tuesday, avocado tempura sushi on Wednesday, navratan korma on Thursday,

and a veggie burger with zucchini fries on Friday is what defines

“American food” to me.

And much the same seems to be true down under: Masterchef

Australia is about cooking a wide variety of cuisines in cities

where Yelp’s lists of different types of restaurants run into the

triple digits.

- That said, I did find that Australian cuisine had a few quirks such

that from the food alone I could tell that I was not watching the

American version.

We can start with the shared British heritage I mentioned above.

While it’s irrelevant to my life, I recognize that in Middle America

it remains the case for a lot of people that a standard meal consists of

“meat and potatoes”, whether that’s a fast‐food

hamburger and fries, or a pot roast and mashed potatoes at home.

The Australian version is “meat and three veg”—all

the dads of the rural contestants claimed that was their standard

fare.

The difference is not in the two extra vegetables, but in the meat.

As the examples that I tossed out above without too much thought suggest,

to me the default meat in America is beef.

I guess chicken is actually eaten slightly more these days, and I suppose

pork is up there too, strange as it seems to me—even before I

became a vegetarian, I never dug on swine.

In Australia, though, it’s all about the lamb.

Per capita lamb consumption is well over twenty times higher in

Australia than in the U.S.

And if it is not the default meat among the general populace, it certainly

seemed to be on this show.

In Australia, though, it’s all about the lamb.

Per capita lamb consumption is well over twenty times higher in

Australia than in the U.S.

And if it is not the default meat among the general populace, it certainly

seemed to be on this show.

- Perhaps even more distinctive?

If lamb is Masterchef Australia’s answer to beef, then

its answer to chicken is… prawns.

Remember on Buffy when Anya talked about a world of nothing

but shrimp?

Masterchef Australia was basically beamed in from

there.

And on those rare occasions that the contestants take a break from cooking

up a mess of prawns, they switch to lobster.

Or crabs.

Or marron, a type of crustacean found in Western Australia.

Or yabbies, a type of crustacean found in eastern Australia.

Or scampi, which sounds like a preparation of shrimp but which in

Australia refers to yet another type of crustacean.

Or Balmain bugs, which are not insects but, you guessed it,

crustaceans.

Go to Australia and your crustacean needs will be met is I guess what I

am saying here.

Spiky underwater monsters with big pinchy claws: they’re

what’s for dinner.

- For the first five seasons of Masterchef Australia,

the last half dozen or so contestants were sent on an overseas trip.

In season one it was to Hong Kong; in season two, London and Paris; in

season three, New York City; in season four, Italy; in season five,

Dubai.

In seasons six and seven, there were no overseas trips, which to me was a

huge bummer—I always thought it was nice that while only one

contestant could win, those who made the top five or the top eight or

whatever the threshold was that season could at least say they went on a

memorable trip.

The overseas trip was finally brought back in season eight, when the

contestants went to… California!

There they were, the Masterchef Australia class of

2016, cooking in the shadow of the Golden Gate

Bridge, while I was probably tutoring a few blocks away.

And what did they cook, having come all this way to sample the bounty of a

whole different continent?

Lamb and prawns.

And what did they cook, having come all this way to sample the bounty of a

whole different continent?

Lamb and prawns.

- So where does Vegemite figure in?

It makes a handful of appearances, but the contestants seem to acknowledge

it as “our national weird thing” rather than “a

perfectly normal and delicious food”.

The judges frequently refer to dishes contestants have cooked as

“Vegemitey”, but it is never a compliment.

Similarly, kangaroo is part of the show’s rotation of meats, but

generally in the context of spotlighting native ingredients alongside

saltbush and macadamia nuts, not in the sense of something one would eat

on a regular basis.

Apparently it’s extremely low in fat and therefore quite hard to

cook well.

- Otherwise, yeah, Australian food seems to be marked by diversity much

as the “American food” I described above.

I guess I could tweak that to say “coastal, urban American

food”, but as over sixty percent of Australians live in one of

five coastal cities,

the difference is academic.

That said, Australia is in a completely different part of the world and

therefore has a different mix from the U.S., and some of those differences

were striking.

Probably the biggest one that jumped out at me: Australia doesn’t

border Mexico.

Most of the contestants were familiar with Mexican food, and one or two

even specialized in it, but taquerias are a “one or two per

neighborhood” thing, not “one or two per street corner”

the way I’m used to.

Australians also don’t pick up a familiarity with the Spanish

language the way Americans do.

So while they could cook food from Spanish‐speaking

countries, what they could not do is pronounce any of it.

For a Spanish challenge they were likely to try to make

“pay‐ELL‐uh”; when Argentina was the country of

the day, that meant “em‐puh‐NYAH‐duhz”;

and asked to make Mexican food, they might whip up some

“TACK‐ohz” by wrapping a few

“chip‐POLE‐teez” and

“JAL‐uh‐PENN‐nohz” in some

“tore‐TILL‐uhz”.

Nor was Spanish the only language to get this kind of

treatment—you don’t want to know what the contestants

did to the phrase “Grand Marnier”.

- So Australia doesn’t border Mexico.

Its land mass doesn’t border anything, but its territorial waters

do abut those of Indonesia, a country with over ten times Australia’s

population and three‐quarters of its GDP.

A couple of Masterchef Australia’s most famous alumni

can claim at least some Indonesian ancestry, but many, many more

contestants have hailed from Malaysia—specifically,

they’ve been Orang Cina, the Chinese Malaysians who make up most of

the Malaysian diaspora.

I guess it’s because Malaysia and Australia are both in the

Commonwealth?

Does that make migration easier?

Seeing all these Malaysian‐Australians made an exclamation point

appear above my head, because while my father was born in India, he grew

up in Malaysia and, apparently, lived in Australia for a few months

before deciding to move to the U.S. instead.

Seeing all these Malaysian‐Australians made an exclamation point

appear above my head, because while my father was born in India, he grew

up in Malaysia and, apparently, lived in Australia for a few months

before deciding to move to the U.S. instead.

- Moving northward lands us in Thailand and Vietnam, and these

countries seem to be the ones that most fill the role of Australia’s

culinary neighbor.

There were a lot of white contestants who specialized in Southeast Asian

food, and even more who talked about having spent weeks or months bumming

around Southeast Asia after college.

And everyone was expected to be familiar with how to make a massaman curry

or a spring roll.

- One group of contestants generally have not had this familiarity, and

have had a limited repertoire overall: those of Indian extraction.

The Indian‐Australian contestants have pretty much only cooked

Indian food.

Give them an apple, a parsnip, and a lobster, and you’re getting

apple‐parsnip‐lobster curry.

And apparently these curries have been phenomenal!

In season four George said that Dalvinder’s cashew lamb curry was

“the best curry I’ve ever eaten in my life”, and in

season eight Marco Pierre White fell all over himself praising

Nidhi’s pepper chicken with parathas.

But Dalvinder came in 19th, and Nidhi came in

20th.

Because eventually you have to make something like a Greek salad.

(Rishikesh from season five was the exception that proves the rule.)

- The contestants of East Asian extraction have not shared this

limitation; while they’ve tended to make East Asian food more often

than the white contestants, most of them have shown equal facility with

Western cooking.

What nearly all the East Asian contestants have had in common has been the

same reason for coming on the show: “I just want my parents to be

proud of me!

They think I’m a disgrace to the family because I want to be a chef

instead of an engineer, and maybe if I win this competition they will

despise me some tiny fraction less!”

This also made an exclamation point appear above my head, because the

message that no matter how much you accomplish, you will always be a

crushing disappointment?

I thought that was just my dad!

Like, I was familiar with the “Why only A? Why not

A‐plus?” stereotype of the Asian parent, but I was never

actually pushed to do better (possibly because I actually did always have

the A‐plus), so I never thought of my father as falling into that

category.

What I didn’t realize until listening to these contestants give

their interviews was that a recurring theme of my own upbringing (that my

interests were contemptible and my achievements were worthless) seems to

span a whole continent.

- I’ve referred to “white” Australians a few times

now, but that word can be used to indicate very different commixtures of

European ancestry.

A white Canadian is ten times as likely to be of French ancestry as

a white American is, and twelve times as likely to be of Ukrainian

ancestry.

Australia’s population is drawn much more heavily from the British

Isles than that of the U.S., and a white Australian is about

2.4 times as likely to be of

“Anglo‐Celtic” origin as a white American

is—and 0.2 times as likely to be of

German extraction.

The most common European ancestry in Australia outside the British Isles

is Italian, followed by Greek—and while white Australians

are barely over half as likely to be of Italian ancestry as white

Americans are, they are three times as likely to be Greek.

There have been lots of Greek contestants on Masterchef

Australia, particularly Greek Cypriots—again,

perhaps because Cyprus and Australia are both part of the

Commonwealth.

George Calombaris is of Greek Cypriot ancestry himself.

English, Italian, and Greek are the three most commonly spoken languages

in Australia—yes, Greek is still ahead of both Cantonese and

Mandarin.

In season five, when contestants were supposed to make fast food, the

three archetypal items they were tasked to create were a hamburger, fried

chicken… and souvlaki, whatever that is.

- So how about “black” Australians?

That term is used to refer to two very different groups: people from

sub‐Saharan Africa, who tend to be very recent arrivals, and

members of Aboriginal groups, who are more distantly related to

Africans than Europeans are.

Only one indigenous Australian has made it into the show, a Torres

Strait Islander in season one; no one indigenous to the mainland has made

it past the qualifying rounds.

Africa has been represented on the show by one white South African and one

half‐Egyptian, half‐Korean contestant.

So I guess that would actually be the thing that would jump out at most

American viewers of Masterchef Australia—no

black people—but how many American Masterchef

cohorts include Somali immigrants or Navajos?

And of course how unusual the absence of black people seems depends on

where you’re from; I’m from California, and as mentioned,

it was the lack of Latino influence that was most conspicuous to

me.

Maybe someone from Michigan’s Upper Peninsula would be struck by

the paucity of Finns.

it was the lack of Latino influence that was most conspicuous to

me.

Maybe someone from Michigan’s Upper Peninsula would be struck by

the paucity of Finns.

- Which brings us to another difference between the U.S. and Australia:

the U.S. is very much a collection of regions.

Long Island City, New York, is basically in a different country from

Grand Island, Nebraska.

Huntington, West Virginia, is basically in a different country from

Huntington Beach, California.

The mix of people is different, the culture is different, the politics

are different… and people certainly speak differently:

the girl who kicked off my first New York City SAT class by announcing

that “Beefaw we stawt Oy needa make a cawwwl so’s

Oy kin foin out when chee‐uh‐leeding practice is

duh‐maa‐ruh” made it very clear that I

wasn’t in Washington state anymore.

Obviously Australia is not entirely monolithic—life in

Fitzroy, Australia’s Williamsburg, stuffed to the gills with

preposterously bearded hipsters, is very different from life in the

80% indigenous town of Fitzroy Crossing, a

3000‐mile drive away in the Kimberley,

where temperatures reach 118°F.

But from what I’ve read, there’s no such thing as an

“Adelaide accent” or a “Brisbane accent” or a

“Canberra accent”, and watching Masterchef

Australia, I couldn’t tell where people were from

based on the way they spoke.

With one exception.

Before watching this show, I couldn’t really tell the difference

between an Australian and a New Zealand accent, but by the time I got to

season six, the one Kiwi in the group sounded like a space alien to

me.

“If we put feush in this deush it’ll be reutch and

deleucious”?

The hell?

- Australia isn’t the only country where accents remain virtually

indistinguishable over a wide geographical area.

People from Seattle sound nothing like people from Texarkana, but neither

do they sound like people from Vancouver… while people from

Vancouver do sound like people from Toronto.

I was always struck by that: the way that up in the Northwest the voices

on the radio sound totally different depending on whether they’re

broadcasting from ten miles north of the border or ten miles south of it,

while the 2000+ miles between Vancouver and

Toronto make no effective difference.

At least, not within the same class stratum.

I once went on a road trip with a Canadian from an affluent background,

and was struck by how, when some working‐class folks struck up a

conversation with him, his voice automatically became a lot more

sing‐songy and he reflexively ended every sentence with the

stereotypical “eh?”—even though they were

working‐class Americans he was talking to.

And from what I’ve read, the same sort of thing is true for

Australia: that the chief distinctions are among broad, general, and

cultivated accents, such that socioeconomics play a much more important

role than geography.

And that observation seems borne out by the show.

I couldn’t tell who was from Sydney and who was from Perth just

from the diphthongs they used, but I sure could tell who worked at a law

firm and who worked at a fish market.

- What all Australian accents have in common is that they’re

non‐rhotic.

Take the word “labor”—in a broad Australian

accent that might come out as “LIE‐bah”, and in a

cultivated one as “LAY‐buh”, but nowhere on the

continent will it come out as “LAY‐burr”.

I have to say, listening to hundreds of hours of non‐rhotic

speech was kind of a stressor!

Not as much of a stressor as having to listen to a Great Lakes

accent—I recently had to shut off a video I was watching

for work because if I had to hear the speaker explain how to approach

a reading comp “p‐yeah‐ssage” one more time I

was going to start biting myself—but enough of one that

in season seven I glommed onto Scottish Fiona as one of my favorite

contestants just because her accent, while nothing remotely like what

I was used to, was at the very least chock full of R’s.

Ditto for Canadian Theresa in season eight.

- Of course, non‐rhotic though it may be, the Australian accent

is not without its charms.

I could listen to Australian women recite adverbs all day.

Something about that “‐ly” at the end, how the L comes

from way back in the throat instead of up at the alveolar ridge, and so

the sound of the Y rolls like an ocean wave from the soft palate forward

to where the bright vowels live.

Rowr.

- But there’s more to a speech pattern than diphthongs and

rhoticity.

Here are some words and phrases that I heard hundreds of times on

Masterchef Australia that I did not know were characteristic

of Australian speech before watching this show:

- How you going?

The equivalent to the American “How’s it going?”—because in Australia it doesn’t go, you do. There is a slightly more elaborate version of this—and this wasn’t a one‐off, I heard it a lot—which is “How are you traveling?”. I don’t want to read too much into what is almost certainly an instance of language meandering fairly randomly, but it is kind of interesting how the American phrasing suggests that life is something that happens to you while the Australian one suggests that you make your own journey through life. - over the moon

I’ve heard this phrase outside of Australian television, but only 0.1% as often as I’ve heard it on Australian television. If Australians are happy about something, it appears they have only two choices in expressing it: they can say that they are over the moon, or they can say that they are— - rapt

…and that’s it. An Australian is never happy, never pleased, never satisfied, never delighted or ecstatic or joyful. Only rapt. Always, always rapt. (Or over the moon, as noted.) Now, excitement is slightly different from happiness, and so it gets another adjective. Excited Australians are— - stoked

…which I have to admit I thought of as California slang. But if it ever was, then boy howdy have the Australians ever made it their own.Now, sometimes things don’t work out. Sometimes you’re so un‐rapt and un‐stoked that you feel like you’ll never be over the moon again. In which case you can fairly be said to be—

- gutted

…another one of those words I’ve heard outside of Australian television, but less often in my entire pre‐Masterchef life than in one season of the show. - under the pump

Australian for “under pressure”. Apparently authorities do not agree on what “the pump” is that stressed Australians are under, but the Australians themselves certainly seem to find the presence of that overhead pump weighing heavily upon them, given the frequency with which they mention it. - stuff up

You might be under the pump because you stuffed something up. I don’t think you’re allowed to say you fucked something up on Masterchef Australia, but I’m pretty sure you can say you screwed something up or messed something up, and no one ever does. So it does seem like “stuffing up” is what people actually say and not just a family‐friendly euphemism. - head down bum up

The stance you must assume when under the pump. I think the idea is that in this stance you are focused solely on the task at hand and are shutting out all outside distractions. This was by far the most common formulation of this phrase, but once or twice a cruder contestant would say “head down arse up”, while those who steered clear of any sort of profanity preferred the formulation “head down tail up”. - get a wriggle on

Australian for “get a move on”, another thing you must do to get out from under the pump. It’s interesting how someone can come up with a more colorful version of a set phrase and then watch it completely supplant the original phrase and become a cliché in its own right. - a red hot go

In the U.S. we do talk about “giving it a go”, though we much more frequently talk about “giving it a shot”, as I supposed is to be expected in a country with eleven times Australia’s rate of gun deaths per capita. In any case, Australians never give it a cold go, or even a lukewarm go—the go is always red hot. - outside the square

Australian for “outside the box”, suggesting that down under, people do their thinking in two dimensions instead of three.

Edwin Abbott sheds a happy tear.

Edwin Abbott sheds a happy tear.

- back myself

To redouble one’s efforts to proceed with a plan, even in the face of doubts and criticism from others. Those critics just don’t understand that I’m thinking outside the square! - in with a chance

Pretty straightforward: this one just means to have a chance. Gary thought that I would stuff up my dish and that I should come up with a new idea, and I was gutted, but I decided to back myself, and it turned out so well I’m over the moon. This is for an immunity pin, and I think I’m in with a chance! - get stuck in

To begin a task and very quickly get immersed in it. Sometimes said of cooking—you can’t spend twenty minutes reading the recipe, you’ve got to get stuck in—but said more often of eating. Enough talking, boys! This looks delicious—let’s get stuck in! - pointy end of the competition

The way virtually every goddamn one of these people referred to the phase when few contestants are left. - good on ya, mate

Australian for good job, congrats, nice work, etc. Though that last American equivalent brings us to this: - nice

Tasty. In Australia, or at least on Masterchef Australia, the word “nice” is used to praise, not to damn with faint praise. And as long as we’re here, a few more items specific to food: - claggy

Unpleasantly thick, though I guess I would find a lot of “claggy” dishes pleasantly thick. Risotto is Masterchef Australia’s notorious “death dish”—people who make risotto very frequently find themselves off the show in short order—and in large part this is because the contestants’ risotto is deemed “claggy”. But when Marco Pierre White gave a master class in how to make risotto, I used his technique, discovered that it worked perfectly and my risotto had exactly the texture he described, and… I didn’t like it! It was too thin and I hated how the grains of rice were all separate. Gimme a nice claggy bowl of risotto so I can get stuck in! - blitz

To use a blender on. My blender whips, chops, mixes, and purees; all Australian blenders blitz. - entrée

Appetizer. I am generally pretty loyal to the usage I imprinted on, but I will cheerfully concede that, etymologically, of course the entrée should be the first course, and the fact that in the U.S. it has somehow come to mean the main course is an abomination. - chook

Chicken. I read that “chook” means specifically a chicken that has been prepared for cooking, but that doesn’t seem to be accurate; on the show people used “chook” to refer to living chickens as well. - noo‐GAH

Nougat. All right, I guess we’re getting back into pronunciation, since I assume the Australians spell noo‐GAH as “nougat”. But they don’t say “nougat”. They say “noo‐GAH”.

They say “noo‐GAH”.

- mock‐uh

Mocha. - fillitt

Filet. - dim sim

Not dim sum! In Australia drunk driving is called “drink‐driving”, so when I heard “dim sim” I somehow assumed the same process was at work and it was just the Australian rendering of “dim sum”. But it’s totally different: a dim sim is a Chinese‐inspired dumpling developed in Australia. - saucep’n

Saucepan. This reminds me of Chandler explaining to Phoebe that “Spider‐Man” isn’t like Goldman or Silverman because he’s not, like, Phil Spiderman—he’s a Spider‐…MAN. C’mon, Australians, it’s not, like, Phil Saucep’n—it’s a sauce…PAN. - shuh‐LOTT

Shallot. Or scallion. You might be thinking, “Wait, what? Shallots and scallions are two completely different foods! That’s like saying that the word ‘lemon’ could also mean a tangerine!” That is because you are more sensible than whoever decided the Australian names for alliums. - swede

Rutabaga. Calling a rutabaga a “swede” initially seemed bizarre to me, but on second thought I guess I’ve eaten my fair share of danishes. - capsicum

Bell pepper. But the Australian word for eggplant is “eggplant”, not “aubergine”, and the Australian word for zucchini is “zucchini”, not “courgette”! - coriander

Cilantro. People keep asking me whether watching so much Australian TV has influenced my own accent at all. When I was in Australia, I did automatically end up speaking halfway between my normal accent and an Australian one—I think that’s a pretty common reflex. But Masterchef Australia had no effect, because I didn’t talk back to the screen. Or, rather, it had almost no effect. I have to admit that I actually do think of cilantro as “coriander” now.Here are some random ones:

- spruiking

Drumming up business. That looks like Afrikaans to me but apparently its origin is unknown. - sparkies

Electricians. Reasonable enough, I guess. - cuddle

A hug. Yeah, in Australia “cuddle” can be a noun. And it does seem to just be a regular hug. To me cuddling is very different from hugging. There are different kinds of hugs, from the awkward “okay, we’re doing this now I guess” lean forward and back tap before going into the restaurant, to the much more meaningful wrapping of arms around each other and squeezing tight. But those are both vertical. Cuddling is not. Cuddling is a sharing of life force through full‐scale body contact over an extended period of time. It’s not necessarily sexual at all—it can be clothed, it can be with your kids—but it is intimate. Except in Australia, where apparently a cuddle is just a hug. - third time lucky, lucky last

Maybe these superstitions are common outside Australia, but I’d never heard them before. (Not in those words, at least; as one reader pointed out, in the U.S. we do of course have “third time’s the charm”.) - [adjective] as

I can think of quite a few similes that have become clichés: blind as a bat, clear as a bell, mad as a hatter, high as a kite, etc., etc. And then a few words have come to function as all‐purpose simile vehicles. “Hell” is one of them: he’s rich as hell, she’s funny as hell, and the ever‐popular “it’s cold as hell out here!”. “Fuck” has come to be used in this manner so often—that movie is scary as fuck, I’m tired as fuck right now—that the Tumblr kiddies abbreviate it down to “af”: “that selfie is cute af and i’m serious af about that”. (I had to go back and edit that to take out the capital letters so it would look more authentically Tumblr‐y.) Anyway, the Australians have gone another way—they just leave the vehicle out of the simile altogether. I know, that seems crazy as! But it makes coming up with similes easy as!There is one complete simile the contestants used all the time, and while it doesn’t strike me as particularly Australian, I heard it so many times that I have to mention it:

- watching it like a hawk

They never watched anything carefully, or kept a close eye on anything—they always, always watched it “like a hawk”. And here are some other phrases that I have now heard from Australians more often than from Americans: - comfort zone

Inside your own personal square. - I’m freaking out!

Some people can’t handle being under the pump. - Generation Y

In the U.S. we stopped using this term shortly after it was coined, when it was replaced by “Millennials” (the same way “Generation X” replaced “Baby Busters”). This seems not to have happened in Australia. I don’t remember even hearing the word “Millennials” on Masterchef Australia. It was always “Generation Y”.

- How you going?

- In the U.S. and Canada, small children are boys and girls, and then

in their tweens the boys start to be called “guys” while the

girls stay girls well into legal adulthood.

And so Elizabeth and I had many exchanges that went like this:

“I saw a cute girl today!”

“As in six and adorable, or as in twenty‐two and hot?”Then at some unspecified point “girl” is abruptly considered demeaning and even in informal contexts you have to use “woman”, while a guy remains a guy forever. Suboptimal. But Australia has come up with a solution to this lack of parity! Unless the way people talk on Masterchef Australia is totally unrepresentative, the solution is this: boys remain boys forever. Girls remain girls forever. It seems like cutesy schtick—because, yes, in the U.S., an eighty‐year‐old might meet up with “the girls” for bridge or with “the boys” for poker, and that is cutesy schtick—but I eventually gathered that in Australia it is not schtick. They actually do just use “girl” to mean “female human of any age” and “boy” to mean “male human of any age”. And “guy” seems to mean “human of any sex”! It was completely commonplace for a female team captain to turn to her two female lieutenants and ask, “Okay, guys, what should our entrée be?” I also noticed that it was quite rare for someone to use a gender‐specific word like “wife” or “husband” or “boyfriend” or “girlfriend”—it was pretty much always “partner”. I’ve never liked that term. To me it defaults to “business partner”, not “romantic partner”. But I guess Nicholson Baker has already covered this territory, so I’ll move on.

- And what we’ll move on to is names.

I talked about this in a minutiae article a while back, but here it is

again.

The winner of season two was a guy named Adam Liaw, whose food did not

look like my sort of thing, but who is smart and funny and seems like a

swell guy, and who was therefore one of my favorite contestants that

season.

We have the same first name.

One thing about the name Adam is that it does not lend itself to

diminutives.

It’s not just that it’s short—a lot of names

with standard diminutives are also just a stressed syllable followed by

an unstressed syllable, yet people still feel compelled to chop off the

latter or replace it with an ee sound: Daniel→Dan/Danny,

Thomas→Tom/Tommy, etc.

But I can attest, based on years of interest in onomastics and decades

of being named Adam, that when your name is Adam, people call you

Adam.

However!

It turns out that the British and Australians have latched onto a fad of

abbreviating everyone's name with a zz sound—Gary becomes

“Gazz”, Harry becomes “Hazz”, etc.—and

to my astonishment, there was a contestant who took to referring to Adam

Liaw as “Azz”.

Crikey.

to my astonishment, there was a contestant who took to referring to Adam

Liaw as “Azz”.

Crikey.

- As for Laura, the eighteen‐year‐old Italian cooking

prodigy who made it all the way to the grand finale in season six?

Well, the fad above dictated that she would come to be

“Lozz”, but apparently that wasn’t considered diminutive

enough for a giggly youngling like Laura.

So “Lozz” became “Lozzle”.

And then “Flozzle”.

And, on at least one occasion, “Lozzledog”.

- The very first change the producers ever made couldn’t wait

until season two—it was instituted a few episodes into the

first season.

To wit: they stopped using the contestants’ full names, and the

captions never revealed them again.

After that, if a season had multiple contestants with the same name, it

was time to break out the nicknames.

Season four had two Julias; one was presented to the audience as

“Jules”.

Season five had three Daniels; one was dubbed “Dan”, one

“Daniel”, and one “Kelty”— his

surname, but in this case the “Daniel” part was never

revealed.

Until I read the Wikipedia article on that season, I figured his name

was Kelty Anderson or something.

- One of the things I most like about Masterchef Australia,

which does not seem to be part of other national editions, is that each

season starts with a sea of anonymous faces, which start to become

slightly recognizable as the field of 24

takes shape—oh, she’s the one who cut the french fries

the fastest, and he’s the one who nearly cut another finger off

every five minutes—and then one day the episode arrives that

premieres the opening credits.

Twenty‐four names accompanied by little representative vignettes to

give a hint of each contestant’s personality and cooking specialty,

scored to the Masterchef Australia theme song by Katy

Perry.

Here’s season four:

- One of the reasons season five was the bad season is that it was the

one season they didn’t do this—they went straight to

the final 22 without letting us see any of the

winnowing.

The opening credits were a sort of skit rather than a montage, which

wasn’t necessarily a bad idea, but it was a skit full of people

we’d never seen before.

- Apparently Katy Perry’s Masterchef Australia

theme song was quite popular, such that I found all sorts of bands and

solo musicians doing cover versions of it, or at least of parts of

it.

My favorite by a wide margin was a drum cover by a Venezuelan musician

named Karla Soto—these fills elevate the song by orders of

magnitude.

Check it out:

- The music during the show is not particularly

varied—it’s the exact same score, episode after

episode, year after year.

It is also extremely heavy‐handed at times—it’s

kind of ridiculous how one of the judges will say, “Your plating

was a disaster—” (horror‐movie sting!) “—but

your balance of flavors was the best of the round!” (abrupt

transition to happy tinkly piano music).

But repetitive as it may get, the music is fairly good.

Like, the “only three minutes left until time runs out, isn’t

it stirring” theme actually is pretty stirring.

- But back to something I mentioned a couple of items ago: that season

five was the bad season in part because all the winnowing took place off

screen.

It looks to me like part of the reason for that was that ratings had been

falling—it turns out that when you’re the most popular

television program in the history of your country, your ratings do tend

to come back to earth a bit after a couple of years—and the

producers decided that a more volatile mix of personalities was called

for.

Since the winnowing process selected for cooking talent rather than for

the potential to cause reality‐show drama, out it went, and the

22 people who were selected included a much

greater proportion of abrasive and annoying personalities than

usual.

I didn’t really like anyone that season, and lots of the contestants

were hard to take:

I didn’t really like anyone that season, and lots of the contestants

were hard to take:

- Clarissa: So inconsiderate that I have to assume she has some

sort of clinically diagnosable psychological deficit.

Stole Faiza’s bench just because she felt it suited her better than

her own.

Sang loudly and annoyingly while other competitors were trying to

concentrate.

Demanded that everyone talk her through all her attempts to cook something,

step by step by excruciating step.

- Samira: Cited Barbie as her role model; said that while she

liked cooking, her real passions were shoes and handbags.

- Nicky: Decided that being captain of a team meant standing

around awkwardly shouting supposedly motivational slogans at people but

not doing any actual cooking himself.

It’s not the sloth that irked me.

It was the motivational slogans.

- Noelene: Grouchy, stubborn, specialized in offal

- Michael: His role in the skit sums him up—he steals another person’s lamb chop and then makes a hideous chortling troll face to celebrate his triumph

- Clarissa: So inconsiderate that I have to assume she has some

sort of clinically diagnosable psychological deficit.

Stole Faiza’s bench just because she felt it suited her better than

her own.

Sang loudly and annoyingly while other competitors were trying to

concentrate.

Demanded that everyone talk her through all her attempts to cook something,

step by step by excruciating step.

- Other seasons featured the occasional bad apple, but for the most

part they showcased the extent to which season five was the felt beard

version of Masterchef Australia.

The closest in tone to season five was season one, back when the reality

show tropes hadn’t been pared back yet.

There was no small amount of contrived conflict, but of the season’s

“villains”, the only actual bad guy was Aaron, who was

the first season’s molecular gastronomy zealot and went on to make

headlines for embezzling millions of dollars from the mining finance

company he founded and spending the money on breast implants and

jewelry for his sexual partners.

(I’ve seen some of the breast implants on Instagram and it’s

safe to say that Aaron’s penchant for unnaturally perfect spheres

went beyond molecular gastronomy.

Grody.)

Another of the season’s “villains” was Kate, a.k.a. Kittykat, a law student with roots in Goa who brought a lot of juvenile drama to the show: she was the girl in the “kiddie mafia” I mentioned above, and became unpopular because of that, and when she unexpectedly survived an elimination and the other contestants seemed chagrined that she had returned to the house, she had a breakdown. “Nobody wants me here! People I thought were my friends didn’t even get up—like, people I thought were my friends are actually disappointed that I haven’t been eliminated. I want my mom!” The crying did not make her more popular in the house. But my heart went out to her! Poor Kittykat! (It has been pointed out to me many times by many people that I am an extraordinarily easy mark for crying girls.) This eventually led to one of the most remarkable twists in all eight seasons of the show:

remember, in season one contestants voted each other off, and when one

vote came down to a

3-3 tie between Kate

and a rather annoying contestant named Sandra who was largely responsible

for the team’s loss, Kate held the tiebreaker—and,

sobbing, she voted to eliminate herself.

OロO, as the kids

say.

remember, in season one contestants voted each other off, and when one

vote came down to a

3-3 tie between Kate

and a rather annoying contestant named Sandra who was largely responsible

for the team’s loss, Kate held the tiebreaker—and,

sobbing, she voted to eliminate herself.

OロO, as the kids

say.

Justine was initially pretty anonymous and was, if anything, framed as an anti‐Kate—she was another early twentysomething, though not a member of the “kiddie mafia”, and seemed embarrassed that Kittykat’s drama was making “Generation Y” look bad. But she survived long enough to carve out an identity for herself as competent and mature beyond her years, a specialist in French cuisine who the visiting chefs tabbed as the only contestant in her group likely to become a serious chef after the show was over. She didn’t; instead she became a successful TV personality with her own long‐running cooking show, Everyday Gourmet.

If I had to pick one more favorite from the first season’s qualifiers, I guess I’d go with Tom; I don’t recall his food being the sort of thing I would seek out to eat, but I liked his cerebral demeanor. Who I’d really want to pick, though, is Sarah; she didn’t make it out of the top 50, but was the only vegetarian to make it even that far in eight seasons. Mary on Masterchef Canada had to cook meat, but didn’t have to taste it; Sarah, by contrast, found herself in a taste test, staring into a gigantic pot of bolognese sauce, and cried and cried. But based on sight and knowledge alone, she filled out her list, and wound up becoming the very last contestant to make it to the next round! It was awesome to see her beaming as she ran over to join the winners. But this was season one, and the judges chose the qualifiers at their own discretion, and Sarah didn’t make that cut—largely, I suspect, to prevent another episode full of tears over mandatory meat.

- Season two:

I’ve already talked about Marion, whose

food was so good that when she was eliminated it was front‐page

news all over Australia, and about eventual winner Adam, whose

tweets are so good that Buzzfeed

regularly

compiles them; I also kind of liked Claire,

the buttoned‐down lawyer who never raised her voice above a murmur

that made all of her interview segments seems like ASMR videos.

Seriously, she was such a low talker that I was surprised that she never

talked Gary into wearing a puffy shirt.

Apparently she had a nightmare experience, as the tabloids tore into

her private life, a bizarre thing for me to learn—bizarre

to think that ASMR Claire somehow caused a furor, but equally

bizarre to think that apparently a lot of people watched this show

primarily as an adjunct to the gossip columns.