|

||

|

Roy Thomas, John Romita Sr., Gary Friedrich, Herb Trimpe, [Doug Moench, Christopher Cooper, Howard Mackie, Chris Claremont,] and Paul Zbyszewski, 2020 |  |

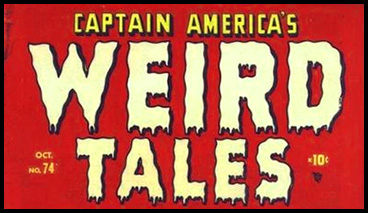

In 1938, Action Comics #1 introduced a character called Superman. He was a gigantic hit, and by 1944, a slew of comic book companies had trotted out over seven hundred different superheroes, trying to achieve the same success. But with the end of World War II, the bubble burst. No new superheroes appeared in 1946. By 1952, the only superheroes still appearing on the newsstands were Superman, Batman and Robin, and Wonder Woman. Publishers tried a lot of genres to fill the gap, but as a sign of which genre wound up as first among equals, take a look at what happened to Captain America in 1949. The logo on the July issue looked like this:

And then the next issue came out, and…

The lead story of that issue was written by Stan Lee, and the Marvel Database gives the following synopsis:

In Hell, the Red Skull has managed to gain access to Satan’s book of damned souls, writing in the name of his hated enemy Captain America in the hopes of trapping the hero in the afterlife forever. On Earth, Captain America is awoken from his sleep by a knock at the door. Answering it he is shocked to find a demon waiting at his door. The demon informs Cap that his soul is now forfeit to his realm and teleports Captain America to the afterlife. […] Satan decrees that the Red Skull and Captain America must fight to the finish. […] The Red Skull attacks Captain America with the Grim Reaper’s scythe […] However, Captain America quickly disarms the Red Skull […] With Captain America victorious, the Devil agrees to let Cap go, erasing his name from his book of the damned.

The four other stories, with names such as “The Tomb of Terror”, do not involve Captain America at all. In fact, this is Captain America’s final appearance for several years. Despite the title, he does not show up in Captain America’s Weird Tales #75.

Captain America would enjoy much more than seventy-four issues of continuous publication when the book was revived in the 1960s, as Marvel Comics rocketed to the top of the industry. A decade earlier, another company, Entertaining Comics, had encountered similar success with a roster of comic books headlined by occult horror titles such as Tales from the Crypt, The Vault of Horror, and The Haunt of Fear. These comics, and EC’s similarly successful and subversive crime, war, and sci‑fi titles, prompted a backlash: psychologist Fredric Wertham published a book called Seduction of the Innocent arguing that comic books were a major contributor to juvenile delinquency, and senator Estes Kefauver convened televised hearings on the matter. The panic led to the implementation of the draconian Comics Code, parts of which seemed engineered specifically to drive EC out of business. The words “horror” and “terror” were banned, as were the subjects that had furnished much of EC’s content: “vampirism, ghouls, cannibalism, and werewolfism”, along with “the walking dead”. “Gruesome illustrations” were also out. Throw in the many clauses that made writing crime comics virtually impossible, and it is no surprise that EC pared its line down to a single title: Mad magazine. And with many of the top genres of the day now out of bounds, it was only a couple of years after the implementation of the Comics Code that superheroes began to make a comeback.

But by the early 1970s, the second heyday of the superhero was beginning to peter out, at least at Marvel Comics. Stan Lee was wrapping up his long stint as chief writer and sole editor, and by 1972 he was officially resting on his laurels as Marvel’s publisher. Jack Kirby had absconded to DC Comics to create the characters and settings that would come to be known as the Fourth World. X‑Men was canceled and, after a gap of many months, brought back as a reprint title. Stan’s successors turned to other media to find trends they might be able to bring to the Marvel Universe. The success of “blaxploitation” movies led to the creation of Luke Cage. The martial arts craze resulted in Iron Fist. And Marvel also started up a horror line. Wait, how? The answer is that in 1971, the Comics Code was loosened up a bit. Zombies remained explicitly forbidden, but “vampires, ghouls, and werewolves shall be permitted to be used when handled in the classic literary tradition such as Frankenstein, Dracula, and other high-caliber literary works written by Edgar Allan Poe, Saki, Conan Doyle, and other respected authors whose works are read in schools around the world”. Marvel immediately responded with Tomb of Dracula (cover date 1972.04), Werewolf by Night (1972.09), and The Monster of Frankenstein (1973.01).

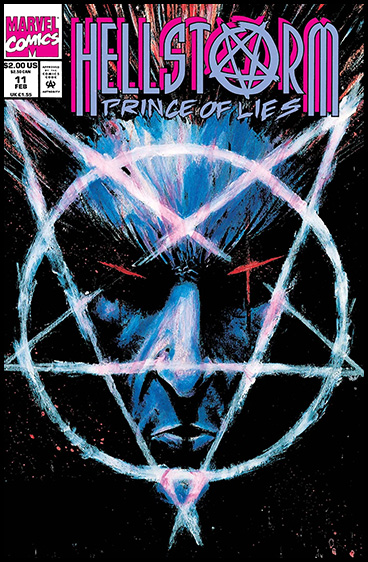

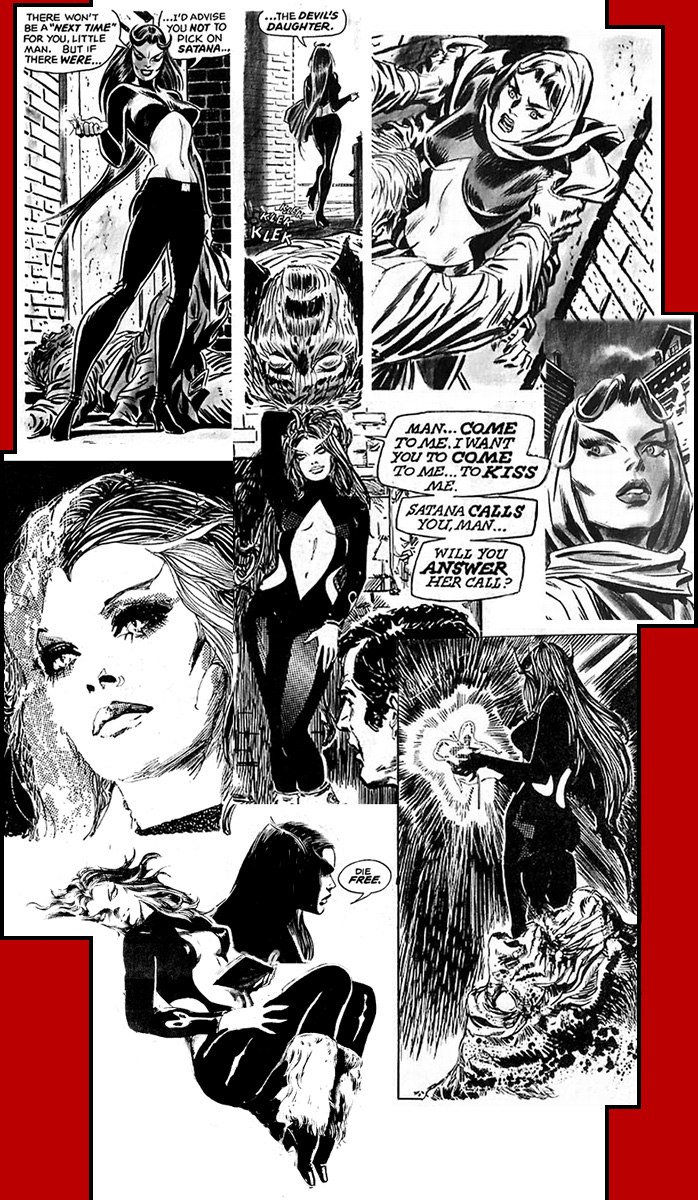

In 1973, The Exorcist was released to a handful of theaters, and the studios were astonished to find lines stretching for blocks. This turned out not to be just a question of supply and demand: the movie was quickly put into wide release, yet the showings remained packed. Over half a century later, The Exorcist has sold more tickets domestically than any other R‑rated movie in history. And that same year, Marvel premiered its own exorcist. Stan Lee had suggested that, to follow up the success that had met Tomb of Dracula, the company should release a title starring none other than Satan, with either a recurring cast of heroes or perhaps some rotating guest stars attempting to foil his diabolical schemes. Stan’s right-hand man, Roy Thomas, was dubious. John Milton himself had found that it’s difficult to make Satan a protagonist without him becoming the hero. Why risk a ’50s-style backlash? Instead, Thomas proposed, why not develop a character who would be the son of Satan? Fighting on the side of right to prove that he isn’t a captive of his demonic heritage… Stan dug the idea, and Daimon Hellstrom, the Son of Satan, debuted in Ghost Rider #1, with his origin detailed a few months later in Marvel Spotlight #12. He kept his star billing on Spotlight well into 1975, then got his own series… but that only lasted eight issues. Daimon wound up sitting out most of the Carter administration, until J. M. DeMatteis plucked him from the ranks of dormant characters and added him to the Defenders for a few years. There he was married off to Patsy Walker, of all people—and that was the month I started collecting comics in earnest. I bought a bunch of issues with a 1983.11 cover date: both the regular Avengers issue (#237) and the annual (#12), Fantastic Four #260, Iron Man #176, Thor Annual #11, and Uncanny X-Men #175. I did not get Defenders #125, though, and so my first encounter with Daimon Hellstrom was a cameo appearance in Cloak and Dagger v2 #8, in which he remains in his civilian identity. His name meant nothing to me. So my proper introduction to Daimon Hellstrom came in West Coast Avengers #14.

This issue came out during Marvel’s 25th anniversary month. It was 1986, well into Jim Shooter’s tenure as editor-in-chief. Shooter had been tapped to pull Marvel out of its 1970s doldrums—in 1978, the year he was promoted to the top spot, it looked like the entire industry might implode—and return the company to its 1960s glory. To Shooter, that meant discipline, both administratively (no more missed deadlines) and creatively: on his watch, every story was to have strong fundamentals, with an emphasis on clarity. He didn’t want 1980s Marvel to rehash the ’60s, but he did want to see a return to what had drawn him to Marvel in the ’60s himself: straightforward superheroics with jokes, cool ideas, and lots of character moments. And “the Son of Satan”? A barechested guy with a pentagram on his sternum, with one foot in the superhero line and the other in the now defunct horror line? He didn’t fit the bill. And so, in West Coast Avengers #14, Steve Englehart introduced me and my peers to Daimon Hellstrom not as the Son of Satan, but as Hellstorm, a guy who would fit in with Hawkeye and Wonder Man, with his mask and red longjohns with a less overtly occult insignia on the front. (The corner box on the upper left of this page is from this issue.) And even though this outfit was treated as a joke as soon as Shooter was gone, the name stuck, at least long enough to be applied to Daimon’s next series.

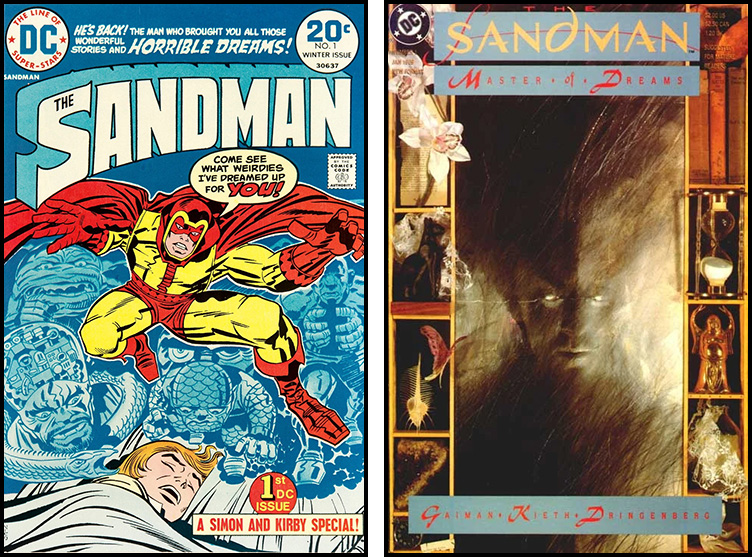

For in the 1990s, Marvel found itself playing catch-up with its chief rival, as DC had a phenomenon on its hands: The Sandman. Karen Berger, the editor of Swamp Thing during Alan Moore’s acclaimed run on the title, had tapped Moore protégé Neil Gaiman to do something similar: revive a series from the 1970s and reimagine it with an avant-garde twist, exploring a corner of the DC Universe far from those inhabited by the likes of Green Lantern and the Flash. Reimagine the Sandman Gaiman did: