Christopher Nolan, 2020 #20, 2020 Skandies

Pattern 25 notes that movies are often experience delivery systems more than they are stories. For all its sci-fi trappings, Tenet is ultimately a delivery system for scenes of guys shooting at each other. Also stabbing each other and punching each other. And sometimes they crash vehicles and blow shit up. The gimmick is that some people and objects are “inverted” in time, so that they act like they would on a piece of videotape on rewind: items leap up off the ground into a person’s hand, wrecked cars bounce around and land on their tires with no sign of damage, that sort of thing. But really all this does is add to the chaos. Apparently I said the opposite about Inception twelve and a half years ago:

Nolan is careful to explain exactly how the logic works […]. It keeps Inception from becoming Primer, Shane Carruth’s impossibly convoluted time-travel movie of 2004. Primer could just barely kinda sorta be followed on a third or fourth viewing if watched with the movie in one window and a detailed diagram of the plot in another. Inception makes sense the first time through […], so bravo on that score.

No bravi this time around—we are firmly in Primer territory here, except I was frustrated by Primer’s incomprehensibility because I kind of wanted to know what was going on, whereas here I don’t care because what’s going on is “bang bang shoot shoot”. With a little “bang bang shoot shoot” thrown in. But its incomprehensibility—and since writing the previous sentence, I have read a raft of “explainer” articles that unanimously concluded that the movie is not just convoluted à la Primer but actually does not make any logical sense—is not even the worst aspect of Tenet. I have mentioned a time or ten that in the movie world there is a mantra that you have to “raise the stakes!”, so that if you establish that the protagonist is having a bad day by having her accidentally spill coffee on her shirt, the studio notes will have you change that to “she spills coffee on her shirt on the way to a job interview” and then to “she spills coffee on her shirt on the way to an interview for a job she needs to get or else lose her house”. And then “house” will be changed to “child who needs cancer treatments”. Anyway, Tenet raises the stakes to a ludicrous degree: if our black ops team isn’t successful, we learn, the bad guy will destroy the entire universe. The idea is that he has received documentation of a formula that can reverse the flow of time not just for a person or an object but for everything; he doesn’t have the technology to start the process specified by the formula, but he can bury it in a particular location, and centuries from now, when the technology has been developed, his confederates can excavate the formula, program it into the doomsday machine, and undo the fabric of reality such that nothing ever existed. His confederates want to do this because climate change has made the Earth uninhabitable. The bad guy wants to do it because, we are told, he’s an egomaniac who doesn’t want the world to exist without him. So he arranges things so that ten seconds after he dies, the arrow of time turns around, bringing the universe to a halt and unraveling the past fourteen billion years.

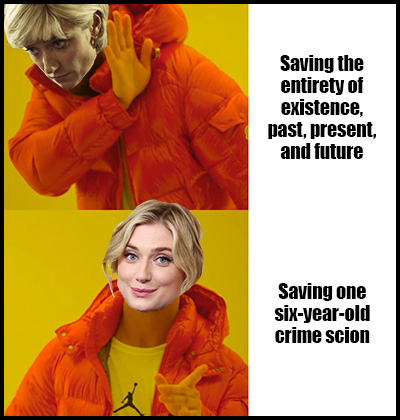

The problem with raising the stakes to this degree, apart from its inherent silliness, is that people can’t comprehend scale, or at least studios are convinced that audiences can’t. You could have Ur‑Quan fleets flying around vaporizing cities, with hundreds of millions killed, and a typical movie would focus on whether two kids and a dog make it out okay. I remember reading an interview back in ’93 in which Steven Spielberg talked about getting pressured to delve into the life stories of some of the Holocaust victims in Schindler’s List, and trying to explain that he “didn’t want people to come away saying, ‘Oh, yeah, the Holocaust. That thing that happened to those five people.’” And yet, at least in U.S. schools, the Holocaust has generally been introduced to students as that thing that happened to Anne Frank. Tenet shows itself to be not remotely up to the task of coming to grips with its own scale. The bad guy is married to an art appraiser who said that a Goya piece forged by a friend of hers was authentic; he is thus able to threaten her with prison time if she leaves him. The two of them have a young son—distantly glimpsed, no lines, a plot device rather than a character—and the bad guy says his wife is free to go with no consequences if she agrees to cut off contact with the child. Though we see him beat her and kick her, she calls this offer “the worst thing” he has ever done. So during one of the shooty crashy sequences, the bad guy holds his wife hostage to get the good guy to hand over the world-destroying macguffin—which, to the sidekick’s disbelief, he does, risking the sum total of all existence for the sake of one life. Later, the bad guy shoots his wife, and to save her, the good guy concocts a wild plan involving time reversal that his more knowledgable associates call “cowboy shit” that threatens the universe, but the good guy insists “I’m not going to let her die”. They do save her life, and bring her into the plan, explaining that her husband is about to destroy the entire universe, though she only agrees to assist after confirming that, when they say “everyone and everything that has lived is wiped out instantly”, that’s “including my son”. As the meme goes:

Then, in the big concluding set piece, her job is to keep the bad guy alive long enough for the good guys to keep the universe-destroying macguffin from being sent to the future and activated—but instead she kills him early, explaining that “I couldn’t let him die thinking he’d won”. Put it all together, and you have a movie in which characters blithely risk the totality of the cosmos, first to save a single life, then to sate a desire for vengeance. And this is portrayed as worthy of applause! Initially I started into this just to show how stupid it is to “raise the stakes” to this degree, how the filmmakers seemed not to comprehend the mismatch of scale—but now that I’ve typed it out, it actually looks worse to me than that. Remember, the whole idea here is that the bad guy is so egocentric that he places no value on anything apart from himself; he’s wiping out all existence purely for the ego trip of knowing in his dying moments that nothing will outlive him. But while the movie wants us to cheer his wife’s moment of triumph—whoo! an abusive asshole meets frontier justice!—she is risking all of existence for ten seconds of personal satisfaction! How is that not monstrous egocentrism? Even her fixation on her son, which the movie wants us to be moved by—wow! the power and ferocity of maternal love!—is egocentrism by proxy. She says her son is “everything”: i.e., literally nothing in the universe matters to her apart from this little packet with half her genes in it. It is this sort of thinking—caring only about yourself and your inner circle, caring nothing for externalities—that has led us on the path, both in the movie and in real life, toward ecological catastrophe (and a host of other catastrophes besides). But Tenet casts as its hero a guy who says flat out that each generation has to look out for itself, and casts “posterity” as the villains. I feel like I’ve heard that somewhere before.

|

|

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tumblr |

this site |

Calendar page |

|||