|

I grew up in Anaheim Hills, California, but I didn’t attend high school there. A school in Fullerton had started up a magnet program to attract students from all over Orange County with an interest in computer science, and in eighth grade a bully had me unhappy enough at my junior high school that I jumped at the chance to switch districts. At first I carpooled with a girl who lived just up the hill from me: her father would drive us to school in the morning, and my mother would drive us home in the afternoon. In tenth grade, she got her driver’s license and could drive herself. I was thirteen, and could not. However, by this point I’d made a friend named Greg West who lived in Santa Ana and took an OCTD bus to school, and it turned out that the closest bus to my house was the very one he took. So at 5:50 a.m. every weekday morning I would get on the bus and we would ride to school together, and most afternoons we’d take the same bus home. We were both on the debate team, and found plenty to debate during these bus rides, as my politics leaned to the left and he billed himself as an arch-conservative. This was 1988, and while I was excited about the possibility that glasnost and perestroika might bring us peace, he was still an ardent cold warrior; when our English teacher had us write advocacy papers, his called for the U.S. military to invade Nicaragua on behalf of the Contras. As we started our junior year, though, we agreed that ’88 was the stupidest campaign season imaginable. There was no discussion of any real issues—the Bush campaign, under the direction of Lee Atwater, had successfully made it a referendum on flag burning, pollution in Boston Harbor, and Willie Horton. “We should run against each other in 2024!” Greg kept saying. “You can be the Democratic candidate and I’ll be the Republican!” Of course, he wasn’t actually that serious about his proposed pact. Neither of us had any plans to go into politics, and even if Greg had, he wouldn’t have been the Republican candidate this year: as he grew up and developed some concern for the welfare of others, he turned away from conservatism and actually wound up becoming a union lawyer. The other sticking point was the year he chose for our big clash. I don’t know why he was so set on 2024. It was never 2020 or 2028—invariably, ’24 was our year. But Greg didn’t make it to 2024; he died in 2019, at age forty-six. The future is not guaranteed to us. Earlier this year I was thinking about how Greg and I would have reacted had my 2024 self been able to travel back to that OCTD bus and fill them in on how the race had actually shaken out: “So, want to know who the candidates are in 2024?” “Nah, what’s the point? They’re just people around our age, right? We wouldn’t have heard of them yet.” “Au contraire! For instance, the Democratic candidate is the incumbent president, Joe Biden!” “Joe Biden? The guy who dropped out last year after a plagiarism scandal? He actually revived his career after that? Wow! But wait… he’s still running thirty-six years from now? Isn’t he like eighty?” “Eighty-one, actually. And the Republican candidate isn’t much younger—hell, he’s older than Reagan is now.” “Really? And it’s someone we’ve heard of? Wait—it’s not Dan Quayle, is it? Do elections keep getting worse and worse to the point that Dan Quayle could actually be the 2024 Republican nominee?” “We should be so lucky. No, it’s someone you know, but he hasn’t formally gone into politics yet. Here, I’ll give it away—who’s at the top of the New York Times bestseller list right now?” “Tom Wolfe? I guess that makes sense—he is a conservative, righ—” “Non-fiction.” “…” “…” “…Donald Trump won the 2024 Republican primaries?! Who’s his running mate, Leona Helmsley?! This is crazy. Why would anyone think Donald Trump could be president?!” “He’s already been president. He won in 2016.” “He did?! But wasn’t that a disaster?” “Yes. Back in 2000 ‘The Simpsons’ had a joke about how America would fare under a President Trump, but they figured he’d just crash the economy the same way he drove all his companies into bankruptcy. It turns out that he’s a lot worse than that. He got impeached twice, the second time for getting a mob to attack the Capitol to prevent the certification of the 2020 election… on his watch 1.2 million Americans died in a pandemic, about three quarters of them due to his mishandling of the response… and, I mean, this bus will reach the end of the line before I could cover even one percent of the corruption and malfeasance of his first term, and that’s when he had the Republican old guard holding him back!” “…” “…” “…so, the Simpsons? You’re telling me that in the year 2000 ‘The Tracey Ullman Show’ will still be on the air?” 🙧 1 Some observers have pointed out that since the pandemic, a fervor against incumbent governments, irrespective of their politics, has swept the globe. For instance, voters in Australia in 2022, Brazil in 2022, and the United Kingdom in 2024 threw out right-wing governments to install more left-leaning ones, while voters in Italy in 2022, Argentina in 2023, and New Zealand in 2023 threw out left-leaning governments to install right-wing ones. The governing centrist party in France was defeated in the 2024 legislative elections by alliances on both the left and the right. But here’s a chart from my article on the 2020 election, updated with two new lines:

The U.S. electorate hasn’t been riding a global wave of anti-incumbent sentiment since the pandemic; it’s been riding a local wave of anti-incumbent sentiment for two solid decades, which has led to a party switch in nine of the past ten elections! Why? One narrative about the 2024 results that seems to have found some purchase is that voters were angry about the rocky post-pandemic economy. But not only does that not explain the ’06–’18 anger, but by many measures, it doesn’t explain the ’24 anger either. Inflation is at 2.6% and unemployment at 4.1%, both low. A couple of weeks before the election, the stock market was at record highs. And GDP was up 2.5% in 2023 and 2.8% in 2024, very respectable numbers for a mature economy. So what’s there to be angry about? Let’s take each of these in turn: Inflation. The pace at which the U.S. tamed inflation was the envy of the world. By the first quarter of 2023, U.S. inflation was down to 6.0%, which compared favorably to that in the European G7 countries: the U.K. was at 10.4%, Italy at 9.1%, Germany at 8.7%, and France at 7.2%. As noted, the U.S. is now at 2.6%, far better off than some of the incoming regime’s models: Orban’s Hungary is at 3.7%, Putin’s Russia at 9.1%, Erdogan’s Türkiye at 60%, and Milei’s Argentina at an eye-popping 250%. But American voters generally neither know nor care what’s happening in the rest of the world. Nor are most of them equipped to appreciate second-order operations like lowering inflation, i.e., slowing a rate of increase. For an item that would have gone from $100 to $109 to $118.81 to instead go from $100 to $109 to $112.27 doesn’t impress them. All that the voters who filled in the bubble for Trump knew was that a Big Mac cost $4.89 under Trump and $5.69 under Biden, so therefore Trump was a better president. Unemployment. During the lo‑o‑o‑o‑ong process of digging out of the Great Recession, it was unemployment rather than inflation that generated the grim headlines. Five hundred applicants for every job opening! A slew of “99ers” who’d exhausted their unemployment benefits after spending nearly two full years out of work! But while unemployment in the U.S. peaked at 14.8% under Trump, the end-of-year numbers under the Biden administration were 3.9%, 3.5%, and 3.7%, with a slight uptick to 4.1% just before the election. This is essentially what the Employment Act of 1946 defines as full employment. Also, the U.S. added 22.7 million jobs under Bill Clinton, added only 500,000 under George W. Bush, added 11.6 million under Barack Obama, lost 2.7 million under Donald Trump, and then gained 15.6 million in less than four years under Joe Biden, beating even Clinton’s pace. So why would voters still hold such a sour view of the economy? Why on earth would they hand the stewardship of the economy to the Republicans, and specifically to the one Republican with a negative record? I suspect that to answer this we need to turn from questions of quantity to those of quality. Time fuckin’ flies, and that “scariest chart in the world” in the pop-up above received its final update more than ten years ago, as the jobs lost in the Great Recession were finally all recovered by the spring of 2014. When unemployment has lost its terror, people have the luxury of wondering whether the jobs they have are actually any good. Does your job pay well enough to give you, as Franklin Roosevelt put it in 1936, not only enough to live by, but something to live for? Have you embarked upon a stable career, or are you a member of the “precariat”? And are you doing something fulfilling, using your talents to make a meaningful contribution to the world, or are you spending more than half your waking life in hell? To expand on each of these a bit:

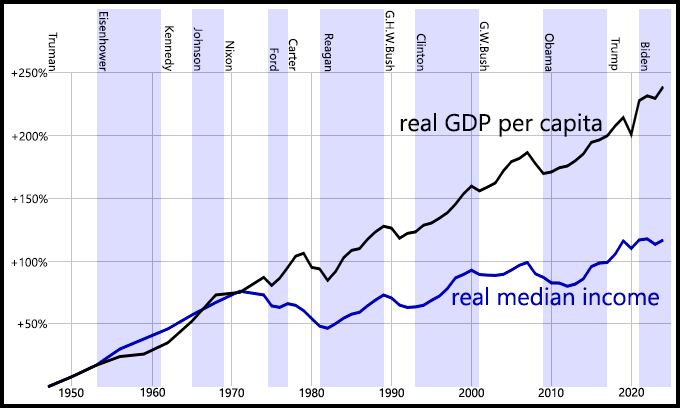

The stock market. At the beginning of 2024, the wealthiest ten percent of American households owned ninety-three percent of all stocks. Half of all stocks are held by the wealthiest one percent. So, to the extent that the stock market tells us anything about the health of the economy, it’s probably a contrary indicator, as it indicates how much wealth is being vacuumed up by the already obscenely rich. Gross domestic product. Ultimately, a lot of the above boils down to this chart right here: |

|

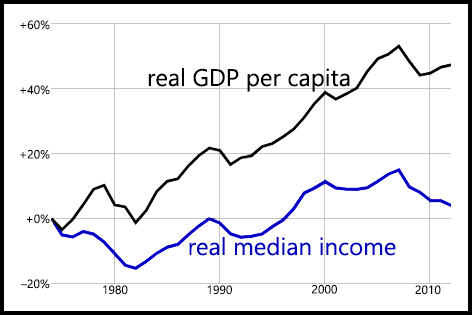

When the income tax was first established in 1913, the top marginal tax rate was six percent. By 1918 it had been hiked to seventy-seven percent to help finance the American entry into World War I, but the three Republican presidents who followed Woodrow Wilson brought it down in stages so that by 1925 it was back down to twenty-five percent. This resulted in a windfall for the rich. They gambled that windfall on the stock market, which imploded, and pretty soon the Great Depression was underway and unemployment was also at twenty-five percent. The New Deal helped some, but the American economy didn’t fully recover until World War II forced the government to spend at the levels that were needed to finally break the back of the depression. To keep the country from going too far into debt, the top marginal tax rate was raised to ninety-four percent, even higher than for WWI. But this time, when the war was over, the tax rates stayed in place: the top marginal tax rate never dipped below ninety-one percent until 1964. And it didn’t go below seventy percent until 1982. Throw in the growth of labor unions under the New Deal, and you get what has been called the “Great Compression”, a thirty-year window when wealth was more equitably distributed than ever before or since, resulting in a dramatic expansion of the middle class. When Millennials lament that they missed out on the era when, on a single income, an average American could buy a suburban house and support a family with several children, this is the era they mean. Productivity was on the rise, and for pretty much the entirety of the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations, the incomes of everyday people rose even faster—that is, an increasing share of the wealth of the nation was finding its way to the people who actually created it. This was an era when the heads of companies made about twenty times what their workers made, not hundreds or thousands of times as much. They bought the big houses on the corners of the streets their employees lived on, not entire Hawaiian islands or yachts the size of football stadiums. Fortunately for the plutocrats, America’s flourishing middle class came with a self-destruct button. The Democratic Party of the mid-twentieth century was an odd coalition of, on the one hand, liberals who supported the progressive policies that had led to the Great Compression, and on the other, racist Southerners who wouldn’t vote Republican because Abraham Lincoln was a Republican and he’d freed the slaves. The latter group had spent a century fighting to ensure that emancipation didn’t amount to much and that the freed slaves and their descendants would constitute a permanent underclass in American society, one that certainly wouldn’t get to enjoy the prosperity of the mid-twentieth century, or even basic civil rights. When African-Americans found success in the 1950s and ’60s fighting for an end to the Jim Crow system that had denied them those rights, a Democratic administration signed the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act into law. Morally, it was the right thing to do; politically, it opened the door for Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan to lure those racist Southerners into the Republican camp, with its very different set of economic policies. The extent to which that stymied progress toward integration is debatable. Less debatable is that it undid the Great Compression. Over the course of the 1980s the top marginal tax rate was slashed from seventy percent down to thirty, and while productivity continued along its postwar trajectory, median income growth slowed catastrophically. Again, look at the chart. Since the two lines diverged, wages have been close to flat. Here’s another version of that chart that starts with my birthdate in 1974:  When I entered the workforce in 1994, real median wages had shrunk five percent over the course of my lifetime. By 2012, they’d only grown four percent since I was born! Yet GDP was up by half. That means that nearly all that excess wealth—again, half the size of the entire 1974 U.S. economy!—had found its way into the pockets of the rich. According to RAND’s calculations, from 1975 to 2018 the top one percent siphoned forty-seven trillion dollars away from the bottom ninety percent. The authors of this study assert that in 2018, not just every household but every individual in that bottom ninety percent would have made an extra $8500 in that one year alone—money that instead got funneled to the likes of Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk. Why do people think the economy is bad if the aggregate numbers are so good? If you want to point to one reason, that’s it! 🙧 2 Of course, you can’t just point to one reason. It’s almost comforting to think that people are unhappy for a reason rooted in reality. But in many cases the real explanation is that they’re pickled in propaganda and are angry about the economy because they’ve been told to be angry about it. Over and over in the days following the election, I read accounts of people trying to convince (usually older, male) relatives to vote for Kamala Harris, only to be met by the same line: “Trump’s economy was better!” So, first, “Trump’s economy” isn’t even a thing. To whatever extent the state of an economy can be chalked up to a president at all, it only makes sense to do so after his policies have had a chance to take hold. There are cases in which that can happen more or less immediately, as when Franklin Roosevelt inspired renewed confidence in the strength of U.S. banks, or as might happen if the economy crashes in response to tariffs Trump imposes in his second term. But it usually takes a little while for the effects of economic policies to manifest themselves. For instance, George Bush was left holding the bag when Reagan’s 1986 tax shift sent the economy into a recession in 1990, so that Bush had to run for re-election with unemployment at eight percent. Bill Clinton did get a second term, so he got to enjoy the roaring economy sparked by his 1993 economic reforms—though that economy probably owes even more credit to Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the World Wide Web. On the flip side, Clinton and his team made some terrible economic decisions, such as repealing Glass-Steagall, which were big contributors to the economic collapse of 2008 that brought George W. Bush’s approval down to a startling minus forty-five. Barack Obama’s 2009 stimulus took ages to pull the economy out of doldrums, but like Clinton, he did secure a second term, by the end of which things were humming to such an extent that he was able to leave office with his approval at plus twenty-two. So those upward slopes we see on the graph after Trump took office aren’t “Trump’s economy”—he hadn’t done anything yet. Those lines reflect the momentum of Obama’s economy. But right-wing media immediately changed its tune about the state of the economy as the calendar apps ticked over to 2017, and we can expect that to happen again. The moment Trump is sworn in again, look for Fox News and its ilk to blare, “Wow, look at that Trump economy! The Dow over 40,000, unemployment at only 4.1%, and inflation down to 2.6%!” But it wasn’t just the propaganda outfits that took this tack. The legacy news media has become functionally identical to right-wing outlets because it has made its supreme virtue not truth, but “balance”. If ever the truth was balanced between the two parties in the U.S. system, it certainly isn’t now. One party put up a candidate who was convicted of thirty-four felonies during the campaign! And judged liable for sexual abuse in another case! And had three other trials going, one for corruptly trying to overturn the 2020 election, one for violently trying to overturn the 2020 election, and one for stealing classified documents, a worrisome thing for someone in the pocket of an enemy power. Report the basic truth, and you come away correctly depicting Donald Trump as one of the worst human beings ever to walk the earth. Meanwhile, Joe Biden is by most accounts a pretty decent fellow. Certainly not flawless—infuriatingly spineless when it comes to getting rolled by Netanyahu, for instance, and about as wrong as could be in judging the qualities needed in an attorney general in the aftermath of Trump’s first term. But present damaging stories about Trump and damaging stories about Biden with their proper levels of alarm, and those scales don’t balance. So, as in 2016, when Donald Trump’s admission that his practice when meeting women was to “grab them by the pussy” was put forward as a wash against something involving which servers delivered Hillary Clinton’s emails, the legacy media cast about for something to hit Biden with and thereby balance the scales. Or, should I say, lazily cast about, generally just repeating whatever the Republican attack lines were. “Groceries cost too much!” All right, yes, I did notice when a carton of eggs went from $3.99 to $4.49. It didn’t strike me as cause to spend three years hammering the idea that inflation was crippling the life of the nation. Especially since, after that jump, the price has stayed at $4.49 for a couple of years now. “Biden’s old!” According to a University of Pennsylvania study, after Trump appointee Robert Hur described Biden as an “elderly man with a poor memory”, the New York Times published no fewer than twenty-six unique stories about Biden’s age over the span of one week. In the same time frame, Trump declared that, if elected, unless our European allies did as he directed, he would pull the U.S. out of NATO and encourage Russia to attack those countries. The Times deemed this worthy of mentioning in ten stories. Before I happened across this study, I did my own quick survey of Times headlines, and there it was, over and over, for years. “At 79, Biden Is Testing the Boundaries of Age and the Presidency”. (Trump will be seventy-nine less than a year after taking office.) “How Old Is Too Old to Be President? Biden Report Raises Uncomfortable Question Again”. (Left out of the headline: as noted, that “Biden Report” was authored by a Republican operative.) Then there’s the old ouroboros play: “Biden’s Age and Memory Rise to Center of 2024 Presidential Campaign”. It’s a Times headline about the fact that the issue is “rising to the center of the campaign” due to previous Times headlines! When Biden dropped out of the race and was replaced by the relatively young Kamala Harris, some Democrats naively hailed it as a deft piece of judo: now Trump would be the old one! He’d be the one whose cognitive decline would be trumpeted every day in the press! Because sure, Biden had a stutter, and had slowed down a bit, but he’d also spent fifty years in Washington and knew his way around the issues. By contrast, Trump’s own secretary of state called Trump a moron, his national security advisor said he had the intelligence of a kindergartener, and they were both being kind: not only is his every appearance a display of appalling ignorance and stupidity, but age has sapped him of whatever mental discipline he might once have been able to summon. Many observers have noted his diminished inhibitions—launching into long disquisitions about Arnold Palmer’s penis, miming fellatio onstage, etc.—and his even more diminished coherence. Look at the unedited transcript of any Trump rally, and it’s not even word salad—more like word coleslaw at this point. Here’s an excerpt I picked more or less at random, from his rally on January 6 of this year—the third anniversary of his inciting a mob to storm the Capitol: We have great people in our military. Took out ISIS in four months. We have great, great people. Um… I, I had, I met some warrior generals that were—they could beat anyone. The people that took out ISIS were unbelievable. Raisin Caine, you know that story, right? General Raisin Caine. I—this—we love Raisin Caine! But we have—I said, “What’s your name?” “Caine, sir.” “Oh, what’s your first name?” “Well, they called me Raisin.” I said, “Wait a minute. Your name is Raisin Caine? I love you, general. That’s what I’m, that’s what I’m lookin’ for! I’m not lookin’ for these stiffs that you see on television.” “Oh, I’m so ashamed. I walked down to the church with the president and he held a Bible.” You know, they attacked that church. You know, that church was on fire the day before. And it got very lucky. We authorized it. They built a fireproof. The area of that church was built along with the White House. And it’s amazing. Two weeks before that, they completed the job of fireproofing the basement of the church. They started a fire in the basement, and it didn’t spread because of the fireproofing, but they, but it got very badly damaged. But it didn’t spread because—she’s laughing. It’s true, right? And it was sort of luck, I guess. But I went down and I held the Bible high and Milley said, “Oh, I shouldn’t have walked with him.” But no, he should have walked with the president. He should have been proud to walk with the president. That was the end of him! That was the end of him! And the other thing, you know, I, I love studying the, uh… if you take a look, I mean, the wars, I don’t know what it is. The Civil War was so fascinating, so horrible. It was so horrible, but so fascinating. It was, uh… I don’t know, it was just different. I just find it. I’m so attracted to seeing it. So many mistakes were made. See, there was something I think could have been negotiated, to be honest with you. I think you could have negotiated that. All the people died. So many people died, you know, that was the disaster. If you got hit by a bullet in the leg, you were essentially going to die or lose the leg. That’s why you had so many people, no legs, no arms. If you got hit in the arm or the leg, it meant you were up, because the infection, gangrene, it was just such a, you know, sort of a horrible time. But that’s—I was thinking to myself because I was reading something and I said, “This is something that could have been negotiated,” you know, and it was just for all those people to die. And they died viciously. That was a vicious, vicious… war. And, uh, in many ways, look, they were all—there’s nothing nice about it. But boy, that was a, that was a tough one for our country. But I think it’s, uh, you know, Abraham Lincoln. Of course, if he negotiated it, you probably wouldn’t even know who Abraham Lincoln was. Uh… he would have been president, but he would have been president, and he would have been—he wouldn’t have been the Abraham Lincoln, would have been different, but that would have been okay. It’s, uh, it would have been a, a thing that—and I, I know it very well. I know the whole process that they went through, and they just couldn’t get along. And that would have been something that could have been negotiated and they wouldn’t have had that problem, but it was a tole—it was a hell of a time. How did the New York Times headline its story about this demented babbling? “Trump goes on offense in Iowa on Jan. 6 anniversary”. It’s an example of a practice that frustrated observers of the legacy media came to refer to as “sanewashing”: providing flattering capsule summaries of Trump’s rambling, giving no indication that the speech described was not statesmanlike oratory but verbal diarrhea. What was newsworthy was not the list of whatever points the reporters thought they could glean from Trump’s incoherent blather, but the incoherence itself. I don’t want this article to devolve into a showcase of Trump’s gibberish, but here’s a moment that actually did get at least a little play in the mainstream news. A woman at the Economic Club of New York asked Donald Trump, “If you win in November, can you commit to prioritizing legislation to make child care affordable, and if so, what specific piece of legislation will you advance?” Trump’s reply: Well, I would do that, and we’re sitting down—you know, I was, uh, somebody, we had, uh, Senator Marco Rubio and my daughter, Ivanka, was so, uh, impactful on that issue. It’s a very important issue. But I think when you talk about the kind of numbers that I’m talking about, that—because, look, child care is child care. It’s, couldn’t—you know, it’s something, you have to have it. In this country, you have to have it. But when you talk about those numbers compared to the kind of numbers that I’m talking about by taxing foreign nations at levels that they’re not used to but they’ll get used to it very quickly. And it’s not going to stop them from doing business with us, but they’ll have a very substantial tax when they send product into our country. Those numbers are so much bigger than any numbers that we’re talking about, including child care, that it’s gonna take care. We’re gonna have—I, I look forward to having no deficits within a fairly short period of time. Coupled with, uh, the reductions that I told you about on waste and fraud and all of the other things that are going on in our country—because I have to say with child care, I want to stay with child care, but those numbers are small relative to the kind of economic numbers that I’m talking about, including growth. But growth also headed up by what the plan is that I just, uh, that I just told you about. We’re gonna be taking in trillions of dollars, and as much as child care, uh, is talked about as being expensive, it’s, relatively speaking, not very expensive compared to the kind of numbers we’ll be taking in. We’re going to make this into an incredible country that can afford to take care of its people and then we’ll worry about the rest of the world. Let’s help other people. But we’re gonna take care of our country first. This is about America first. It’s about “make America great again”. We have to do it, because right now we’re a failing nation. So we’ll take care of it. Thank you. Very good question. Clearly, the story here is that Trump was asked about a pretty basic plank of his economic platform, and not only did he try to bullshit his way around the fact that he had no answer, but he sounded like Miss Teen South Carolina in the process. Who knows—maybe he was taking notes on what he overheard when he barged into the dressing rooms at the teen beauty pageants he used to run, a practice he used to boast about. And how did the New York Times headline its story about this flailing non-answer? “Trump Praises Tariffs”. And when called out on their role in greasing the skids for fascism, journalists have tended to respond not by defending their choices, but minimizing their impact. “There’s [sic] so many people who think that if the American media had used slightly different language to describe Trump, Americans wouldn’t like him,” tweeted one. “And I’m sorry to tell you we have less influence than ever. We understand this better than you do”. While trying to dig up this quote, I discovered that the author had recently posted a follow-up asserting that “all the people who spent the last twelve months close-reading NYT story structure were wasting their time”, because a Data for Progress survey had shown that those who followed the news broke 52/46 for Kamala Harris while Donald Trump was up 52/31 among those who listed their news consumption as “none at all”. I’m not sure that’s quite the defense this guy seems to think it is—that forty-six percent of people could follow the news and still consider Donald Trump an acceptable candidate strikes me as a pretty damning indictment of the failure of the news to make clear that he is not. But, yes—as bad as the legacy media has been in serving as a check on fascism, I suppose that to complain about it is a bit like fussing over the ant problem in the kitchen when termites are about to bring the whole house down. One of the big initial takeaways from the 2016 election was that finding out what voters were hearing had become exponentially harder. A generation earlier, we’d heard that AM radio, once thought to have been effectively killed off by FM, had come to be dominated by right-wing talk stations, with prescient observers warning anyone who would listen not to underestimate what might happen when every tractor, every shop floor, every long-haul truck had a radio blasting Rush Limbaugh and his clones around the clock. Then Fox News came to the fore, leaving millions grieving that their elderly parents were spending their retirement years stewing in the invective of the likes of Bill O’Reilly, Glenn Beck, Sean Hannity, Tucker Carlson, and every day growing that much more unrecognizable: even the good parents were now frightened and hateful. But these were still broadcasts, out in public view. What 2016 brought to light was how many people had been swayed by preposterous stories that had been making the rounds under the radar, passed around by racist uncles on Facebook. The example that stuck with me was that of the West Virginians the Boston Globe profiled who insisted that Hillary Clinton had ordered up thirty thousand guillotines that she was going to use to execute the sorts of people who voted for Trump. “All you got to do is pull it up on the Internet,” one of them explained. This is lunacy, not far removed from the notion that she’s a shape-shifting lizard from the Draco constellation, but all it took for some Russian troll farm to convince them was to get those words onto their smartphone screens, because their grip on reality was just that weak. The buzzwords at the time were that we were living in a “post-truth world” full of “fake news”. The latter term almost immediately became infamous, as Trump seized upon it and applied it to any story in the mainstream media that he didn’t like—and as his legions of followers started using it the same way, it was soon robbed of its power to refer to the sorts of disinformation it was meant to describe, such as the guillotine story. As scholars of fascism explained, the point of disingenously crying “fake news! fake news!” was less to get people to believe that true things are false, or that false things are true, than to get them to stop believing that there even is such a thing as truth. But that was 2016. I didn’t know what Facebook’s algorithms were feeding people—I thought that, like me, folks were just getting baby pictures and vacation photos from the randos who’d sat behind them in fifth grade—but at least I’d heard of Facebook. The updated takeaway from 2024 is even more unnerving. My only real experience with it is very tangential. In December of last year I got a flat out on the highway near Martinez—I told that story in the penultimate item in that month’s minutiae article. This was the second time I’d needed a tire changed in less than a year. That March, when I still lived in Albany, California, I’d taken the car to Albany Tire, where I’d had good experiences in the early 2010s… only to discover that, in 2023, they now had Newsmax playing in the waiting room. Not even Fox News—one of those even farther-right networks that had started up on the basis that Fox News was just a bunch of pinko commies. So, no more Albany Tire for me. In any case, the December flat came after I’d moved to El Cerrito, so after making an appointment at the tire shop just up the road, I called for another tow. I rode along for the couple of minutes it took to get there. I was used to being subjected to execrable music in tow trucks, but on this driver’s radio was just a couple of guys talking. As the tire shop came into view, I was taken aback to hear them start insulting women—and then, a moment later, horrified when one of them revealed himself to be Andrew Tate. What the fuck?! I only knew of this guy because he’d popped up in the news a couple of times: first, because he’d taunted climate activist Greta Thunberg about the emissions from his fleet of cars, and then, because he’d been placed under house arrest in Romania, where he was charged with rape and running a sex trafficking ring. And, what, he had a podcast? And this guy downloaded it? Where the fuck do you even get an Andrew Tate podcast? Is this what has replaced Rush Limbaugh? Are the farmers and shop workers and tow truck drivers all steeped in misogynistic poison by rapists with Eastern European empires of sex slaves? Do I actually have to be nostalgic for the racist uncles trading stories about guillotines? Actually, that’s another thing—the West Virginian guys fit the description of the kind you’d expect to be wearing red caps in the daytime and white hoods at night. But during the 2024 campaign, there were rumblings that Trump was somehow gaining ground with many of the very demographics he’d spent his life vilifying—showing that there would have to be more to saving democracy than just waiting for Boomers to die off and waiting for the share of the population the Census Bureau called “Non-Hispanic White” to dwindle. And here was a case in point: a relatively young African-American guy, living in the bluest metro area in the country, getting his brain rewired for patriarchal fascism. And I don’t even know by what channels this propaganda is getting to people anymore. Therefore, I obviously have no idea how to go about combating it, either. Especially scary to me is that this right-wing noise machine has been up and running in various forms for over thirty years now and no one else seems to have any solutions either. Counterprogramming doesn’t seem to work. So when you spin the dial on the AM band you get nothing but Rush Limbaugh? All right, we’ll start up our own station! With Al Franken and Janeane Garofalo! That got a tenth Limbaugh’s audience and quickly died. Fox News is setting the agenda for the rest of the news media? Here’s Al Gore with a cable news channel to serve as a liberal alternative! It had so little impact that few even noticed when it arrived or when it disappeared. The obvious response is that the audience just isn’t there—that it’s like a TV station trying to compete with the Super Bowl by putting on opera. But votes from the Fox News era tell a different story:

That’s not a ten to one ratio in the right wing’s favor. Most years there are more blue votes than red ones. So is it a mismatch of medium and audience, then? The flattering interpretation is to say that a reluctance to unquestioningly consume propaganda is part of what distinguishes the left from the right. Or that hatred and fearmongering lock the brain into a primitive neurological reward cycle in a way that love and open-mindedness don’t. But not only does that seem obnoxiously self-congratulatory, I doubt it’s even true—I certainly prefer to get my news from outlets that share my ideological viewpoint—and, worst of all, it doesn’t actually offer any solutions. 🙧 3 In the aftermath of the 2016 election, I thought that education might be part of the solution, and one I could even contribute to. Maybe critical thinking skills could inoculate some minds against right-wing propaganda! That was one of the realignments pundits had observed in 2016, after all: while once high education levels had, if anything, steered people toward the Republicans—because the educated tended to have better jobs with higher incomes, and dating back to the nineteenth century the Republicans had been the party of the rich—now it looked like a direct correspondence had emerged between low education and Republican vote share. The flip makes sense, as Trump is the stupidest candidate ever put forward by a major party, with historians ranking him dead last in intelligence among the presidents—behind the likes of Warren Harding and Andrew Johnson—and linguists flagging him as a huge outlier among politicians in speaking below a fourth-grade level, making noted dullard George W. Bush look like an orator for the ages by comparison. Trump’s ideas would also make most fourth-graders roll their eyes. Trying to stop hurricanes by dropping nuclear bombs on them? Or stop wildfires by raking the forests? Or stop covid by injecting people with bleach? But here’s the thing. You know how Trump wouldn’t shut up about “the late, great Hannibal Lecter” at his 2024 rallies? The premise of The Silence of the Lambs was that Clarice Starling consults Hannibal Lecter in the Buffalo Bill case on the theory that one serial killer might have insights into another serial killer that sane people might not have. Similarly, Trump’s defining political gift has been that he is stupid enough to have some insight into what stupid voters will go for. Barack Obama, campaigning for Kamala Harris in October, expressed no small amount of exasperation about one example of this. During the first covid lockdown in 2020.03, the Democratic Congress passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, which sent $1200 to adults who made up to $75,000 a year. Donald Trump’s demand in exchange for signing the bill into law was that the aid go out in the form of paper checks with his name on them, along with a letter bearing his sawtooth signature. The Democratic calculus in going along with this seems to have been that it wasn’t worth delaying the checks to put up a fight. After all, everyone knows that the power of the purse lies with Congress, not the president! If anything, Trump will make himself look bad by gauchely trying to claim credit for a bill that passed in a unanimous, bipartisan vote! And… millions of voters gave him credit. Obama actually sputtered in frustration recounting this. “Some folks would be like, ‘Well, Donald Trump sent me a check!’” he groaned. I was groaning myself during the presidential debate in September, when Kamala Harris rolled out what was apparently going to be the Democratic line on one of the very few policy proposals Trump had put forward: tariffs on all imports. “My opponent has a plan that I call the Trump sales tax,” Harris said, “which would be a twenty percent tax on everyday goods that you rely on to get through the month.” Now, it has long been observed that Democrats have been quite bad at tagging concepts with phrases that stick. Republicans seem to do it effortlessly: an example that springs to mind is the estate tax. Currently, $13,610,000 can be passed to heirs tax-free, so over ninety-nine percent of inheritances have no tax collected on them at all. But above that line, a portion is collected by the government, up to a top rate of forty percent. Thus, only most of a massive hoard of wealth goes to descendants who did nothing to earn it, while some goes to fund vital goods and services for ordinary people. Republicans started calling this the “death tax”, and suddenly you had legions of AM radio listeners who made eighteen thousand dollars a year demanding its repeal. So I’m sure Harris’s consultants batted around ways to similarly reframe tariffs in a way voters wouldn’t like. Hey, how about we just call them a “sales tax”? People hate sales taxes, right? Maybe not as catchy as “death taxes” but it’ll do the job! Except it didn’t do the job at all, because Harris didn’t actually say that she was referring to Trump’s proposed tariffs, and even if she had, just calling them “sales taxes” wouldn’t have had any impact. Why do so few modern Democrats try to follow in the footsteps of FDR? When Franklin Roosevelt took to the radio for his first “fireside chat” as president, the nation was in the midst of a banking crisis. So how did he start his address to all the folks listening in their living rooms? He explained how banks work! Because he recognized that “comparatively few” Americans could truthfully say that they “understand the mechanics of banking”, and “the overwhelming majority of you who use banks for the making of deposits and the drawing of checks” were mystified by the crisis because they had only a nebulous idea of what a bank even was! Only a handful of people outside the world of finance had ever heard of “fractional reserve”—when Roosevelt explained that “when you deposit money in a bank, the bank does not put the money into a safe deposit vault”, listeners were shocked! And that is the level at which I was pleading for Harris to pitch her critique. “People don’t know what tariffs even are!” I uselessly protested to my screen. “You don’t need a focus-group phrase! Just take your sixty seconds and explain how tariffs work!” Instead she trotted out her zinger, and Trump just replied, “I have no sales tax. That’s an incorrect statement. She knows that. We’re doing tariffs on other countries.” And millions of people thought, “Oh, Harris was lying. She said Trump wanted a sales tax but he actually wants a tariff. Those lying politicians! Always with the lying!” And then after voting for Trump and seeing that he’d won, they finally went to Google and typed in “what is a tariff”. While battling Ted Cruz for the Republican nomination in 2016, Trump famously declared, after finishing +37 among Nevada voters with a high school education or less, “We won with poorly educated [sic]. I love the poorly educated!” It will undoubtedly come as no surprise that misinformed voters went for Trump by wide margins: +26 among those who thought violent crime was at all-time highs in 2024 (it had fallen to pre-pandemic levels, and even pandemic levels were lower than any year from 1970 to 2010), +19 among those who thought the inflation rate was rising in 2024 (it was falling, as discussed above), +17 among those who thought U.S./Mexico border crossings hadn’t fallen in 2024 (they had, by nearly 80%). I also mentioned above that Trump had done very well among uninformed voters who simply didn’t follow the news. What has baffled pundits for close to a decade now has been the fact that Trump has been able to get not just the misinformed but also the uninformed to not only favor him but actually vote for him. And often only for him! In the five swing states that had Senate races, Trump received nearly 570,000 votes—over five percent of his total in those states!—on ballots that were blank apart from the presidential race. Many of those 570,000 voters had never cast a ballot before, and many will likely never vote again; I guess we’ll see whether any of us get to. Another element of the postmortem articles about the 2024 election that jumped out at me was this: I spent a whole bunch of pixels above talking about disinformation, but I kept running into quotes from voters—inevitably Trump voters—who had cast a ballot on the basis of the most perfunctory disinformation there is: the denial. “I voted for Trump because he said he wouldn’t have a sales tax!” “I voted for Trump because he said he had nothing to do with Project 2025!” “I voted for Trump because he said he wouldn’t ban abortion!” “I voted for Trump because he said he wouldn’t cut the ACA, just Obamacare!” These voters were often young, and often female—the exact demographic that Harris was supposed to win by overwhelming margins. Yet the clear implication is that they didn’t even consider voting for the Democratic ticket. For them the choice was to vote for Trump or not to vote at all. They had a few concerns about him: I’m glad my state has no abortion ban! Will Trump take the Texas laws nationwide? The man caught in over thirty thousand documented lies during his first term said no, these voters said okey-doke, and they oblingingly signed up for four more years with him in charge. In 2016 my response to this sort of thing was that clearly these voters had never had to do a worksheet on trustworthy vs. untrustworthy sources. In 2024 I’m more inclined to believe that they did once have to do such worksheets and voted this way in part as a slap at those of us who drew those worksheets up. Universal education is a relatively recent social innovation. Surprisingly, the American school system has its roots not in England but in Prussia, where Frederick the Great launched a program to place both boys and girls in compulsory classes, taught by trained educators, starting at age five and ending when the children reached their teens, at which point some could continue on to secondary school and from there possibly to university. Popularized in the U.S. by Horace Mann, the aims of the American version of the system were described by Ellwood Cubberley, the founder of the school of education at Stanford University, as “social efficiency, civic virtue, and character”. Social efficiency: instead of farmers teaching their children how to farm and businessmen teaching their sons how to run a business, give all children a foundation to pursue whatever path their talents and interests take them. Maybe that business would be better run by one of the farmer’s kids! Civic virtue: a republic depends on the ability of its citizens to serve well in their roles as decision makers: to stay informed about the issues of the day, to be good judges of character, and so forth. A concept that frequently comes up on the AP U.S. History exam is that of “republican motherhood”, the notion that it was important to educate girls in civic virtues, even in the days when women couldn’t vote, because the groundwork for good citizenship couldn’t wait for children to get to school—they had to start learning the American way from their mothers while still in the cradle. As for character, a couple of years ago I took a class on the Nordic countries from a professor whose previous area of specialization had been modern Asia. He brought up the fact that, in multiple indices tracking corruption around the world, Nordic countries made up four of the six least corrupt nations on the globe. Some chalked this up to factors such as wealth, ethnic homogeneity, and freedom from colonialism, he said, but he didn’t buy those arguments. Bangladesh was ethnically homogenous but grotesquely corrupt. South Korea was ethnically homogenous and rich, but its score did not impress. On the flip side, he said, look at Finland. Finland had spent more than a century under Russian occupation. Finland had been extremely poor between the two world wars. Yet, even then, it had been remarkable for its low corruption. His contention was that the main cause was the character that Finnish culture tried to inculcate in each successive generation: one based on trust in others, a commitment to fairness, a disrespect for undue privilege, and an unwillingness to let infractions slide. Much the same was true for the other countries at the top of the list, he contended; the one exception was Singapore, where corruption was kept in check by a combination of high salaries, to make bribes less tempting, and harsh punishments. But top-down solutions didn’t work outside of microstates, he said, so if the likes of Bernie Sanders really wanted the United States to start taking cues from the Nordic countries, only a full-spectrum bottom-up approach could hope to have any success. The reason I say “full-spectrum” is that it just doesn’t work to put the entire burden of instilling rising generations with character and civic virtue, the sort of citizenship needed for a republic to function, onto the education system. One of the reasons working in public education is so punishing is that it is expected to serve as the remedy for all sorts of societal ills, in flagrant disregard of the exchange rate between prevention and cure. For instance, the school where I taught had a larger than average achievement gap between students identified as white and those who were not. This reflected the unusually wide gap in the lived experience of these students. White students in this town were likely to be children of professors, successful artists, tech workers, and the like; many lived in multi-million-dollar homes up in the hills. The circumstances of non-white students tended to be quite different. Many were very recent immigrants who had fled from war zones. Others were immigrants of a more local sort, commuting a fair distance to school from impoverished neighborhoods outside of town. Some didn’t even have fixed addresses. Over the years, the school had tried many initiatives to try to reduce the achievement gap. Honors classes were abolished in the name of shared experience and peer-to-peer education. Homework was eliminated, on the basis that you can’t expect students to write essays in a homeless shelter, or when they have a bunch of younger siblings they’re relied upon to look after as soon as class is out. When I left, there was a vigorous debate going on about the possibility of instituting separate grading systems, so that white students would be penalized for late work and non-white students would not. One math teacher was steadfast in maintaining that all of this was counterproductive: year after year in the email discussion threads, he argued that trying to find ways to make up for differences in privilege was like coming up with better ways to bail out a sinking boat—it just made it that much easier to put off fixing the damage that was swamping the boat in the first place. “People tell us that we should stay in our classrooms and do impossible things, ‘because you need to recognize that you are powerless to change the way things are,’” he wrote. “But that is not true! We have power, and if we act collectively we have a lot of power. Protest the massive socioeconomic inequality in our city, state, country, and world.” He called for teachers—not just us, but basically all teachers—to go on strike demanding “a combination of progressive taxation, guaranteed income, increased minimum wage, and high quality universal healthcare”. Anything less was pointless. “Research going back at least four decades shows that the primary factor in predicting a child’s academic success is their family’s wealth. Despite what the neoliberals want us to believe, we cannot educate our way to equality,” he insisted—italics his. Yet teachers remain charged with doing the impossible and educating our way to, if not equality, then at least civilization. But usually the civic virtue and character elements of education aren’t a big part of the pitch to students to get them to take it seriously—the social efficiency is. It isn’t long before kids are bombarded with the message, both inside and outside the classroom, that unless their families have money or connections to prop them up, how well they do in school is largely going to determine their lot in life. And the stakes are higher than they used to be. Again, there was a time when, if school wasn’t your thing, you could still get a job at the mill or the mine or the plant and lead a solid middle-class life. But as the middle class has been hollowed out, life outcomes have become a lot more polarized. It’s not much of an exaggeration to say that either you’re the cardiologist performing heart bypasses or you’re flipping the burgers that make all those bypasses necessary. In some places this has made education fiercely competitive, which brings its own set of problems—it kills the joy of learning and undermines the spirit of peer collaboration that, at least according to teacher credentialing programs, modern education is supposed to be built around. But in other places the problems are quite different. American schools are funded at the state and local levels. Therefore, if you’re in a poor area—say, one of the vast rural regions in the red states that went for Trump close to unanimously—how well are you going to learn, and how well are you going to be able to compete for future opportunities against students in more affluent districts, when your school relies on a slew of fill-in teachers on emergency credentials, teaching in dilapidated classrooms with few supplies? (Actually, in some areas qualified teachers are so hard to come by that districts have given up finding them locally—in rural schools foreign language classes, for instance, are often conducted online these days.) And the effect of poverty on school quality pales in comparison to its effect on students. Neglectful or abusive home lives, stress responses trained on constant danger, simple hunger—they all cause behavioral problems that teachers are expected to overcome by waving the magic wand of “classroom management”. But I’ve read plenty of articles about teachers getting hired in the sorts of places Trump won—teachers who weren’t outsiders, but products of deep red rural America themselves—and even when these issues weren’t major factors, these teachers were soon looking for other work due to, as one of them put it, “just the level of disrespect and non-interest” they encountered. And this wasn’t adolescent rebellion: the teachers in these articles taught elementary school. How do kids that young develop such an antipathy to education that they torment their teachers? If the question were about a kid, you might look into personal reasons. It might be chalked up to the oddly tautological “oppositional defiance”, say. Or maybe the child finds school difficult and frustrating due to a lack of “scholastic aptitude”; after all, by definition half the population is below median intelligence. But when it’s nearly everyone? That’s something these students must be picking up from their community. And we do see regional hostility to education, both in terms of policy (such as teacher pay) and more directly, with parent protests and angry appearances by community residents at school board meetings. Why the hostility? Some of it is about the content of public school instruction. When children take a science class and learn that the Earth is not six thousand years old but 4.54 billion, and that the proof is not what a handful of Iron Age priests put forward as the revealed word of an unseen god but rather radiometric dating that you can verify for yourself once you learn how to use a mass spectrometer, the churches don’t like it because it undermines their authority, and the churchgoers don’t like it because it undermines their identity. When children take a history class and learn about, say, the 1921 Tulsa massacre—in which a white mob firebombed one of the wealthiest African-American neighborhoods in the country, burning the forty-block district to the ground, murdering dozens and injuring hundreds—those who identify with the mob demand that the incident be removed from the curriculum. They call teaching such things “woke”, and while that term has become an epithet on the right for “anything I don’t like”, in this case it fits with the original meaning: it’s a long-suppressed incident whose revelation has the potential to wake people up to some of the themes of American history. In this case the theme is, why are people with African ancestry poorer than other groups in the U.S.? Because wealth has been systematically denied to them. This was most obvious over the course of centuries of slavery, when the fruits of their labor were flat-out stolen, but more recently the practice of redlining and the design of New Deal policies largely kept them from sharing in the gains the middle class accrued during the Great Compression—and, in between, we see terror and violence employed in places like Tulsa to destroy whatever affluence they may have been able to obtain. The “fuck your feelings” folks don’t want their kids to hear about this because they fear it might make them feel bad about being white. It may even encourage them to think that perhaps basing society around a racial hierarchy is bad, when, as Lyndon Johnson pointed out, that hierarchy is the only thing keeping many of these people off the very bottom of the social totem pole. And thus they demand that schools keep their kids asleep. The thing is, you can look into the roots of ideology like this, but ideology quickly becomes its own thing. A community may have initial grievances that make them hostile to intellectual inquiry, but pretty soon anti-intellectualism is part of the local culture in and of itself. Again, there are cultures in which academic achievement is not just prized but demanded, where an A is shameful because it’s not an A+, and they have their own problems. But in the sorts of places that voted for Trump, academic achievement is more likely to be despised. Schools, meant to be learning communities, become social hierarchies where the valued qualities are not mental or moral, but material (are you wearing the right clothes?) or even physical (doesn’t the archetypal American high school have football players and cheerleaders at the top?). Kids with good grades are scorned, and not just at school. This old Simpsons joke in which Rainier Wolfcastle describes his upcoming movie didn’t just come out of nowhere: Now, you might think, okay, sure, that’s not a social environment that’s going to turn out well-informed citizens with critical thinking skills. You’ll be able to collect a lot of their votes just by blatantly lying about basic facts and by proposing to tackle problems with simplistic solutions that would only make things worse. But that’s actually not where I’m going with this. I’m more interested in the anger. Again, if the message is “your lot in life is largely determined by how well you do in school”, but you and your community don’t value doing well in school, you’re going to be angry at the fundamental underpinnings of society in our age of education. Officials whose constituencies hail from these sorts of places thus leverage that anger in their favor by making performative ignorance part of their political personae. We saw it in the first presidential debate of 2000, when Al Gore ran through some of the math in George W. Bush’s proposals, mentioning that a hundred billion dollars would be cut from Medicare to pay for a tax cut for the wealthiest one percent, and that Medicare premiums would go up eighteen to forty-seven percent. Bush’s reply? “Look, this is a man who has great numbers. He talks about numbers. I’m beginning to think not only did he invent the Internet, but he invented the calculator.” Put aside the canned zinger—to me the real key is the contempt packed into the line “he talks about numbers”, aimed at collecting the votes of everyone who ever flunked a math class and hates those fuckin’ nerds who talk about percents and shit. Nowadays you have the likes of Marjorie Taylor Greene insisting that COVID‑19 must have been a Chinese bioweapon, turning a deaf ear to virologists’ explanations of how a bat coronavirus could have naturally evolved to infect humans via an intermediate host: “I don’t believe in that type of so-called science,” she scoffed. “I don’t believe in evolution. I believe in God.” Is Greene actually that stupid? Yes, but she also knows that she can collect all the votes of everyone who ever flunked a biology test because the teacher wanted students to answer on the basis of all that confusing stuff about mutation and natural selection that the reverend says will send us to hell. And now, as we proceed ever deeper into our second Gilded Age, more and more people find that the message about the importance of doing well in school was right. You didn’t follow Rainier Wolfcastle’s son to that fancy East Coast college, and now your lot in life sucks. No blue-collar middle-class life for you. Instead, just like the teachers warned, you ended up spending day after soul-crushing day mindlessly ringing up purchases of imported Chinese crap at the Wal‑Mart, relying on food stamps to be able to eat because your paycheck isn’t enough to live on. And you’re angry. So you vote for the guy who’s going to take away your food stamps. That may not seem like a very logical response. But you see it as a way to lash out at whoever set the rules of the game that you lost. The tagline for my 2020 election article was “Eleven million vote to watch the world burn”—a reference to the fact that sixty-three million people had voted for Trump in 2016, when he’d never held office and was therefore still something of an unknown quantity… and then in 2020, after four years of chaos, corruption, and catastrophe, he upped that to seventy-four million! The fact that Trump was destroying America motivated eleven million people who hadn’t voted for him the first time around to opt to give him a second term. However, the eternally high “wrong track” numbers got more than fifteen million people who hadn’t voted for Hillary Clinton to vote for Joe Biden. Trump exists in a perpetual state of rage, but the narcissistic injury that came with getting voted out sent him into a meltdown, especially after his attempt to cling to power via a combination of bureaucratic malfeasance and mob violence (temporarily) failed. Having racked up even more crimes in the effort, it became clear that his only chance to avoid dying in prison was a combination of breathtaking fecklessness on the part of the new Democratic administration and somehow becoming the only president other than Grover Cleveland to return to the White House after getting voted out. He retreated into revenge fantasies, ranting on social media, and even on the campaign trail, about the day that he could jail or even kill prosecutors and judges for the crime of prosecuting and judging his many, many crimes. This was basically the only line of attack that Trump’s Republican rivals were willing to bring to bear, for fear of alienating the Trump cult that makes up the majority of the Republican base: that, oh, yeah, Trump had been an awesome president, for sure, but sadly he was stuck in the past, talking incessantly about the 2020 election and his personal grievances, when we needed to be focused on the future and the battle against the woke mind virus!! But Trump, as always, doubled down. Michelle Obama has spent Trump’s entire political career declaring that Trump “is not who we are”; Trump was willing to bet that he was. “I am your retribution” became his new slogan. To some it seemed nonsensical—did he think tens of millions of voters cared about getting back at Jack Smith? But apparently what tens of millions of voters heard was this: you don’t need to be part of the Trump cult to vote for him. You can stay in your intellectually lazy “Politicians? I don’t like any of ’em!” comfort zone. Because you’re not voting for a person—you’re voting for retribution. This is how you get back at the system that pushed you behind this cash register, or into this Amazon warehouse, or beside this deep fryer. It’s not, of course! It’s the predatory capitalists who bankrolled Trump’s campaign and whom he has been selecting for key government posts who pushed you into that Wal‑Mart, stealing your $8500 a year in order to pump their own net worths up into the nine- to twelve-digit range. That’s another one of those themes you can learn about in history class: manipulating the working class to get it punching down instead of up. One of the most commonly heard criticisms of Trumpism is that it takes the anger people feel at the bailed-out banks that foreclose on their houses, at the health insurance companies that after decades of premium payments deny their claims, and directs it at vulnerable populations: immigrants, trans people. But my main takeaway from the 2024 election is a bit different. Earlier I wrote about a few of the roots of anti-intellectualism. And just now I suggested that another of those roots is anger stemming from the perception of many people that the established structure of American society, particularly the education system, functions as a barrier between them and a satisfactory life. The equity courses in my teacher credentialing program seemed to be largely in sympathy with this notion! Personally, I’d place the lion’s share of the blame on the way the structure of American society has been warped by post‑1980 capitalism, such that those barriers do become more formidable with each passing year. But those courses argued that, no, education actually does serve to perpetuate social injustice more than remedy it, and we need to fix that. The retributionists don’t want to fix it, though. They want to smash it. They’ve had enough of what Cubberley termed “social efficiency”. But education’s role in directing people into suitable work, which these folks reject, is tangled up with its promotion of civic virtue and character. And so they reject those things too. This allows them to support Trump. Let’s return to that stage where Barack Obama was complaining that “Some folks would be like, ‘Well, Donald Trump sent me a check!’” He continued: “Let me make sure you all understand this—Joe Biden sent you a check during the pandemic, just like I gave people relief during the Great Recession. The thing is, we didn’t put our name on it, because it wasn’t about feeding our egos, it wasn’t about advancing our politics, it was about helping people!” It was a message that went hand in hand with one of the main messages of the Harris campaign: Donald Trump is all about himself, but we Democrats want to help you! Here’s Harris herself during the debate: “I’m going to invite you to attend one of Donald Trump’s rallies because it’s a really interesting thing to watch. You will see during the course of his rallies he talks about fictional characters like Hannibal Lecter. He will talk about ‘windmills cause cancer’. And what you will also notice is that people start leaving his rallies early out of exhaustion and boredom. And I will tell you the one thing you will not hear him talk about is you. You will not hear him talk about your needs, your dreams, and your, your desires. And I’ll tell you, I believe you deserve a president who actually puts you first. And I pledge to you that I will.” I’m sure that seemed like a winning line to take. He’s egocentric! We’re altruistic! He only cares about himself! We care about you! But to the voting bloc that served as kingmakers in 2024, this kind of talk is counterproductive. Oh, so the Democrats want to help others, do they? Well, you know who says we’re all supposed to help others? School! So fuck that! It’s all bullshit! Outside school walls, outside the progressive bubble, Americans spend their lives immersed in a culture of self-promotion: the music they listen to, the social media they scroll through… though it’s not like this is anything new. Just ask P. T. Barnum. So Donald Trump slapping his name on everything from Trump Vodka to Trump Steaks to the Trump Bible feels real to them. Humility feels fake. It also leads Democrats into a trap, because the cynics can ask, oh, if you want to help us so much, why haven’t you? What have you ever done? And Democrats can try rattling off their recent accomplishments—what about the American Rescue Plan? what about the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act? what about the Inflation Reduction Act?—but the voters have never heard of these things, because recent Democratic leaders have found it gauche to tout their accomplishments in a way that would break through to this segment of the public. Of course, all the problems I’ve been laying out in this article are operating simultaneously, so we also have to take into account the right-wing propaganda machine I discussed above, which does its best to stifle positive news or paint it as negative. Look at the one Democratic accomplishment that did get the name of a Democratic leader attached to it: the Affordable Care Act, which Republicans tried to smear as “Obamacare” when they thought it would be unpopular. When Republicans tried to hobble the law by striking portions of it, such as the individual mandate, it actually increased the ACA’s popularity because the parts that remained, people liked. Medicaid expansion! No denial of coverage due to pre-existing conditions! No cancellation of coverage due to actually getting sick! Premium assistance payments! Loss aversion comes into play here as well: what really solidified support for the ACA was Trump’s attempt to get rid of it in 2017, thwarted by John McCain. So there you go, right? A Democratic accomplishment people actually know about! Except, as with tariffs, this overestimates what people know. What actually happened was that public opinion of Obamacare and the ACA diverged. And in those cases when I’ve seen low-information voters told that Obamacare is the ACA, time and time again I’ve seen the same response: first comes the denial, then they look it up, then it sinks in, and then comes the flailing attempt to flee from cognitive dissonance. I saw an interview with one woman who said, “Okay, it does say here that Obamacare is the ACA, but that means we should keep the ACA but get rid of the Obamacare parts, because Obama is bad.” Another exchange I’ve seen multiple times on interview segments like these, at Trump rallies and conservative conferences and the like, has gone like this: