|

|

…and other than Spider-Man, I didn’t know any of these

characters!

So it was back to the library to pick up books about

Marvel superheroes, such as

Origins of Marvel Comics and

Bring on the Bad Guys.

But I couldn’t find anything about the most

interesting-looking characters in the puzzle.

Who was that yellow and red robot guy over at the center right, for

instance?

And who was that

in the green and yellow costume?

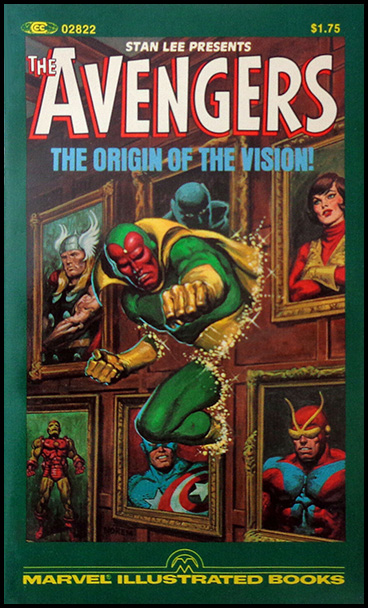

I got the answer to the latter question when I found myself in a

bookstore that turned out to carry “Marvel Illustrated

Books”—paperbacks containing a couple of comics

with the color removed and the panels rearranged to fit the smaller

pages.

And one of them, which I eagerly snatched up, was all about that red

guy:

So that was how I first read Avengers #57

and #58, featuring the debut of the Vision.

Or, rather, the debut of the Silver Age version of the

Vision.

In the Golden Age, way back in 1940, Marvel Mystery

Comics #13 had launched a character who went by the same

name, this one

with the power to teleport between wisps of smoke.

Twenty-eight years later, Avengers writer Roy

Thomas was fixated on the idea that even though the Marvel Universe had

begun with Fantastic Four #1 in 1961,

Marvel’s predecessor companies Timely and Atlas had nearly thirty

years of history that Thomas could mine for content—and

one example of his fixation was that he wanted to make the Golden Age

Vision, whose last appearance had been in 1943, into an Avenger.

Stan Lee vetoed the idea—he wanted the next Avenger to be

an android.

And so Thomas created a mysterious android called the Vision whose

costume looked virtually identical to the alien’s.

Except the Avengers’ resident scientist at the time, Hank

Pym, pulled the “akshually” card and declared that the

Vision was “not an android… but a

synthozoid!”

Okay, so what’s a synthozoid?

Or a synthezoid, as it would soon be spelled?

How does it differ from an android?

And how does either differ from a robot?

Etymologically, it would seem that an android is distinguished from

other robots by its resemblance to a man.

But I can’t recall the the Avengers’ arch-enemy Ultron ever

being described as an android, despite the fact that he’s got two

arms (with elbows), two legs (with knees), two hands with five fingers

each, a head with two eyes and a mouth—he is

nevertheless always called a robot.

I guess it’s because he’s made of metal and his face is a

fright mask, so he can’t pass for human?

Yet the Vision is an android despite his tomato-red skin and solid

black eyes.

Saying “no, he’s a synthezoid” doesn’t help

matters, because that’s an even stricter category: Pym explains

that it means “You’re basically human in every

way—except your body is made of synthetic parts!”,

and years later, the Vision himself explains, “Some men have

prosthetic arms, or legs, or eyes! I have prosthetic

everything!”

That is, rather than just being a robot with an outer covering that

makes him look human(-ish), he’s got a heart and lungs and

kidneys and whatnot, just all made of plastic.

Except in later years when we see the Vision disassembled, whoops,

he is a robot on the inside, full of circuit boards and copper

wiring.

And two pages after specifying that the Vision is a synthezoid,

Pym himself goes back to calling him an android.

So the comics’ explanation of who (or what) the Vision is

probably sounds more than a little handwavy.

And it is.

But it could have been much handwavier.

Recall that Stan Lee came up with the idea of mutants in large part

because he got tired of having to come up with unique explanations

for how all his characters got their powers.

Posit the existence of mutants, and you can say, “They were

just born with ’em, okay?”

Similarly, Roy Thomas and company could have played off the Vision

like so: “Hey, folks, the newest Avenger has density powers!

He can make his body more durable than solid steel, or turn ethereal

and walk through walls! How? He’s an android! He was built that

way!”

And then that would be the last you’d hear of him being an

android.

Marvel had done it before.

That’s how the company had played off its first superhero, back

in 1939.

Marvel Comics #1 starts with a man

introducing himself as “Professor Horton”, who then

declares, “As you all know, I’ve been working on a

synthetic man—an exact replica of a human

being!”

The problem is, his creation has to be kept in a vacuum chamber,

because when exposed to air, it bursts into flame.

But the automaton learns how to control the reaction, and since it

speaks like a human, acts like a human, and thinks like a human, the

press dubs it—or, rather, him—“the

Human Torch”.

By #4, the Torch has adopted the civilian name “Jim

”,

and the fact that he’s a robot has fully receded into the

background.

Not so for the Vision.

In 1968, Stan and Roy saw the induction of the Vision into the

Avengers as a prime opportunity to teach their young audience some

lessons about the importance of diversity and inclusion.

“You accept me… though I’m

not truly a human being?” the Vision asks.

Pym replies, “The five original Avengers included an Asgardian

immortal… and a green-skinned, tormented behemoth! We ask merely

a man’s worth… not the accident of

his condition!”

Of course, the Vision soon found that not everyone in 1968 shared this

attitude.

On his first venture out in public after he was announced as the newest

Avenger, he found that “the world holds no warmth… no

welcome for one who is not fully human”, as we see some meathead

shaking his fist at the Vision and growling, “Crummy

androids… tryin’ to take over from

real people!”

He’s wearing a pork pie hat rather than a MAGA cap, but the

allegory should still be pretty clear.

But the Vision’s status as an android is more than just an

allegory for membership in a demonized minority group.

Right from the get-go, the comics played up the idea that the Vision

seemed cold, stiff, and yes, robotic on the outside, while on the

inside, he was roiling with emotion.

It was this android who, in

,

shed a tear upon being accepted into the Avengers.

It was this android who, with no need to sleep, would spend his nights

reading poetry and listening to jazz records.

It was this android who was wounded to the quick by every slight,

would snap at his friends and then apologize, would go off to

sulk and then berate himself for giving in to self-pity.

And he spent a lot of time falling into despair about how he was a mere

machine, a pale imitation of life, so much less than human because he

couldn’t really feel—the irony, of course, being that

his feelings were stronger than anyone’s.

The obvious story arc once the character was established, Thomas

thought, was to offer the Vision the prospect of a romance.

Maybe an android could cry, but could an android love?

Now, at the time, there was only one woman on the team: the

Wasp.

But she was married to Hank Pym.

The only other woman who had ever been an

Avenger was the Scarlet Witch.

So Thomas brought her back.

Wanda Maximoff, the Scarlet Witch, had first appeared as an X‑Men

villain—sort of.

X‑Men #1 established Magneto as

the X‑Men’s arch-enemy; when he reappeared in #4, he had

his own team, the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants, to back him up.

But only two of his four new underlings, the Toad and Mastermind,

actually were evil mutants.

We learn in their very first appearance that the other two, Wanda and

her twin brother Pietro, were only on the team out of a sense of

obligation: Wanda had accidentally set a village on fire with her

unpredictable hex power, and Magneto had saved her from an

outraged mob.

In that first appearance of the Maximoffs, Magneto’s

scheme is undone not by the X‑Men, but by

Pietro—a.k.a. Quicksilver, one of the all-time great

sobriquets in the world of comics—who dismantles

Magneto’s doomsday device in a fit of conscience.

In their second appearance, the following issue, it’s

Wanda who zaps Magneto’s thingamajig and thereby saves

the X‑Men.

They are clearly being set up to switch sides and become the sixth

and seventh X‑Men—but Stan had a trick up his

sleeve.

Yes, in X‑Men #11, they do quit

the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants… but one week later, in

Avengers #16, they sign up to fight

not under Professor X but Captain America!

(When Wanda explains how they’d been forced to serve Magneto,

Stan, recognizing that perhaps having the X‑Men square off

against the Brotherhood in four consecutive storylines may have been

overkill, amusingly footnotes her speech “As shown in practically

every issue of X-Men”.)

Wanda begins her Avengers tenure as part of “Cap’s Kooky

Quartet”, in which the personalities line up thusly: Captain

America is the experienced leader, prone to brooding over his lack of

a private life; Hawkeye is the earthy hothead who spends most of his

time sassing Cap; Quicksilver is… another hothead, overly

protective of Wanda; and Wanda doesn’t have to worry about her

personality overlapping with that of another character, because she

doesn’t have one.

At least the Wasp had some traits, as demeaningly stereotypical as

they were: she was the Avengers’ ditzy mascot, who flirted with

any man within a ten-mile radius in hopes of getting Hank Pym jealous

enough to propose to her.

But in her first stint as an Avenger, the Scarlet Witch is a

blank.

Her dialogue is either purely functional (“Hawkeye, look

out!” “I will use my hex power!”) or serves the

purposes of the plot.

Does she support Cap’s leadership or side with the boys?

Does she resent Pietro’s domineering ways or meekly submit

to them?

It varies from one page to the next, depending on what gets the

characters to the next story beat!

But as I’ve discussed in many of these articles over the years,

one of the paradoxes of storytelling is that the emptier a character

is, the better that character works for a large segment of the

audience.

Ciphers have few conflicting characteristics to get in the way of

audience identification—or, in the case of a love

interest, to conflict with the readers’ own desires.

In this sense, even if Wanda’s hadn’t

been the only unmarried female Avenger, she would have been ideal for

Thomas’s purposes.

There was nothing in her personality to suggest that she would be open

to a relationship with an android… but there was nothing in

her personality to suggest that she

wouldn’t.

Because, y’know, there was nothing in her personality.

She returned to the team in issue #75, cover date 1970.04.

By #81, she was staring at the Vision with her thought balloons

filling up with reflections like “Before now, I’ve

always thought of him as cold…

aloof… but I was

wrong—so wrong!”

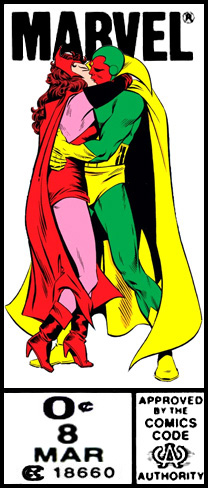

And then came years of the two of them going in for a kiss, only for

the Vision to turn away: “No! It must not

be. I’m an android—a mere

copy of a living being—a thing of

plastoid flesh and synthetic blood!”

But while “Can an artificial being truly love?” was the

primary theme of the Vizh/Witch relationship, the fact that the

Avengers’ acceptance of the Vision had served as an allegory

for the virtues of integration meant that, when he and Wanda did

become a romantic couple under the pen of Thomas’s successor

Steve Englehart, they served as an allegory for interracial

relationships.

Pietro is tapped to play the role of the intolerant patriarch:

“I am the head of our family—and I

forbid you to love that thing!”

As for the wider public, Englehart has the younger generation

on board with the relationship, while their elders are more

likely to side with Pietro.

One writes Wanda a hate letter, intercepted by Captain America:

“Androds are agents of the devil,” it reads in part.

“Wize up befor its to late! Androds have no soles!”

This adversity just makes their love for each other stronger, even

ferocious—and it becomes Wanda’s defining

characteristic.

By the time I started collecting comics in the mid-’80s, the

Vision and the Scarlet Witch were married and living in Leonia, New

Jersey, and I was going to say that not much had changed, as one Roger

Stern Avengers issue had arsonists burn down

their house—but, no, upon a quick reread, I see that

the emphasis was different.

The bigots weren’t angry that an android (read: member of a

racial minority group) was married to a human woman (read: befouling a

sweet flower of white maidenhood)—they just hated the two

of them, separately, merely for existing.

Part of this was that enough time had passed since

Loving v. Virginia that panic over

miscegenation was no longer a major part of the zeitgeist.

Another part was that Wanda was not human but a

mutant—in fact, she’d recently been revealed to be

Magneto’s daughter—and with the X‑Men having

risen from B‑listers to Marvel’s top sellers,

anti-mutant hysteria was now Marvel’s primary allegory for

bigotry of all sorts.

(In the twelve-issue limited series that provided the logo at the

top of this article, Englehart followed up on the arsonists: “I

don’t want a mutie living in Leonia!” is at the top of

their list of complaints.)

And then there was the Vision’s evolution to consider.

One of the fundamental components of storytelling is the character

arc.

This can be a matter of a character being changed by external

factors—e.g., when the Avengers’ butler, Jarvis,

reflects in Avengers #280 “how

little like the giddy young girl I met so

long ago” the Wasp had become, it is largely due to the abuse

she had suffered in her marriage.

But sometimes the steps of the journey to come are baked into a

character as introduced.

The Vision was an android who fretted about the extent to which his

status as an artificial construct made him less than human; it seems

only natural that his character arc would involve him becoming

less robotic, at least in fits and starts, and partaking in more and

more elements of human experience.

And that is what we see in the twenty years following his debut.

I mentioned that he grows interested in poetry and jazz, pursues a

romance with the Scarlet Witch that leads to marriage, and moves with

her to New Jersey.

The Vision was actually the primary focus of the first long

Avengers storyline I collected out of the

spinner racks: he becomes team leader, and at the end of it, he frees

himself of a “control crystal” Ultron had built into his

synthetic brain.

As a result, his speech balloons switch from his trademark rectangles

to regular round ones—signaling that he no longer sounds

like a Mattel Intellivoice, but like

.

And that’s the Vision’s status quo during the Englehart

series mentioned above: he’s just a guy who instead of being full

of microplastics is full of macroplastics.

This series also emphasizes the Vision’s family

connections: Roy Thomas had established that Ultron had programmed

the Vision with the brain patterns of a dead superhero called Wonder

Man, and with Wonder Man now back from the dead, the series makes a big

deal of the fact that the Vision has a “brother”, and

through him, a mother, and “Cousins! Nephews! Aunts! Black

sheep!”

So the next step in the Vision’s journey through the range of

human experience is parenthood, and nine months of the series are given

over to Wanda’s pregnancy, culminating in the birth of their

twins, Tommy and Billy.

How could an android sire children, you ask?

Magic!

When first introduced, Wanda was said to have a “hex power”:

all she had to do was point, and an unpredictable disaster would

occur.

This could be anything from a pitcher of water falling off a table to

the wiring in a wall-sized supercomputer exploding.

In short, she had Stan Lee’s favorite power: she could do

whatever the plot required!

By the time I was reading comics, subsequent writers had added a

scientific veneer to the hexes: “The very laws of probability

warp and alter before her eyes!”

For instance, in the first issue of Avengers I

ever bought, #237, the Scarlet Witch defeats Electro by improbably

making “all the carbon dioxide in the room cluster around

his head, so he’d pass out from temporary lack of

oxygen”.

But that was her mutant power.

Back in Avengers #128, a member of the

Fantastic Four’s entourage had offered to help her develop a

parallel set of powers: “I know of a desire in you—a

desire to be more than you have

been—a desire for your name to be more

truth than

poetry—and I flatter myself that I

possess some small expertise regarding

witchcraft.”

This was a character Stan Lee and Jack Kirby had introduced in

Fantastic Four #94, very late in their

run; she was a thin, quite elderly woman whom Reed and Sue Richards

had selected to serve as the nanny to their baby son, Franklin.

This self-described “frail old lady”, black cat in

tow, fended off an attack by the Wizard, Sandman, and Trapster, and

thereby won the approval of the FF’s leader: “It

seems that

was the perfect choice for us after all!” he proclaims.

Now a few years had passed and Franklin was no longer in need of a

nanny, and Agatha selected Wanda as her

“new charge”.

Thus, by the time Wanda and the Vision had started talking about how to

start a family, Wanda was just as likely to be reciting incantations

while sitting at the center of a circle of candles as she was to be

using her mutant abilities.

When Kurt Busiek became the Avengers writer

in the late ’90s, he tried to reconcile Wanda’s power sets

by having Agatha explain that the imprisoned demon Chthon had, from

the moment of Wanda’s birth, shaped her mutant abilities to

make her a potential vessel for his re-emergence; in so doing, he had

given her the ability to wield chaos magic, unconsciously at first,

but with purpose if ever she were to study to become a sorceress.

Which, more than sixty years after her debut, is how she’s now

portrayed: she’s no longer a student, no longer a dabbler, no

longer a mutant playacting as a magic user, but is an actual

sorceress with students of her own.

You might say it’s the culmination of her character arc.

But there are creators, and certainly there are marketing types, who

find the very concept of character arcs misguided.

They believe that once a character catches on with an audience, the

job of those who work on that character is to give the people what

they want over and over again—to iterate through what

John Byrne called the character’s “established

motifs”.

Say you get tapped to write Spider‑Man.

You gotta play the hits!

Taking photos for J. Jonah Jameson to pay the rent!

Checking up on Aunt May to make sure she’s taking her

medicine!

Ducking out in the middle of a date because a bad guy has

attacked!

Which bad guy?

Oh, one of the regular rotation: the Green Goblin, Doctor Octopus,

the Lizard… for Spider‑Man you’ve got a lot of

options.

And sure, you can launch a storyline that shakes up the status

quo, but after a year or two, you have to put the toys back where

you found them.

So if Peter Parker uses his established scientific acumen to start up

his own tech firm, that’s fine, but it can’t be too long

before the company collapses and Pete has to go crawling back to

Jonah.

If Aunt May, who appeared to be about eighty-five as drawn by both

Ditko and Romita, finally succumbs to one of her various ailments,

that’s fine, so long as she’s quickly

resurrected—perhaps a “genetically altered

actress” died in her place?

If Pete gets married, meaning no more dates with comely lasses who

don’t know he’s Spider‑Man, that’s fine, so

long as he gets divorced… wait, no, we don’t want him

to be a divorcé, because that’s a permanent change, so

maybe he can make a deal with the devil to retroactively alter the

timeline.

And then you can get back to playing the hits!

Now, you may ask, doesn’t that get boring?

If it gets boring for the creator, Byrne asserts, he should just move

on to another title whose star has a different

set of established motifs.

But boring for the reader?

How?

Comics are for kids!

Say you tell a story (e.g., someone else takes over for Steve Rogers

as Captain America) when a certain reader is eleven.

If you rehash it five years later, well, that kid is now sixteen, and

too old to be reading comics!

He’ll never know the story was done all over again, just as when

he was eleven he didn’t know the stories he was enjoying had

already been done when he was six!

There’s a reason I keep mentioning John Byrne here.

As noted, Steve Englehart had been the primary caretaker of the Vision

and the Scarlet Witch since 1972; he’s the one who married them

off and the one who made them parents.

When their limited series ended, he brought them over to his ongoing

book, West Coast Avengers.

But shortly thereafter, Englehart left that book, in a dispute with

the editors over their interference in a storyline involving his pet

character, Mantis.

And John Byrne took over.

I was excited!

Byrne was one of the very top names in ’80s comics, both for

story and art, and even though I’d only caught the tail end

of his long run on Fantastic Four, I’d

really imprinted on the issues I had read.

And in interviews he was saying that the reason he’d chosen

West Coast Avengers as his next gig was that

he had a story about the Vision and the Scarlet Witch he wanted to

tell.

Well, you can probably put two and two together here.

The guy who’d started his Fantastic Four

run with a story called “Back to the

Basics!” thought that it was high time that these

characters stop progressing through life stages and return to their

“established motifs”.

In the case of the Vision, that meant turning him back into an

emotionless robot.

Of course, this was a wild misreading of the character.

The Vision had never been emotionless; right

from the get-go he was the most emotional member of the team.

And he’d never been a robot, either.

All that rigmarole about “synthozoids” was Roy Thomas

trying to put a giant blinking sign saying “NOT A ROBOT”

over the Vision’s head, but apparently John Byrne missed

it.

And the whole point of Hank Pym paraphrasing Martin Luther King’s

“I Have a Dream” speech was to establish the parallel

between the Vision and a member of a visible minority group: the

Vision’s synthetic body didn’t make him less than, or even

in any way that truly mattered different from, anyone else.

Byrne’s stance thus amounts to “Judge you by the content

of your character? Not when you have skin like

that, I won’t!”

In interview after interview, he insisted that the Vision was

nothing more than “a toaster”, and it was a travesty on

Marvel’s part to allow Wanda to marry one—seemingly

unaware that he was echoing the Marvel Universe bigots who stood in

for our world’s opponents of interracial marriage.

Wize up befor its to late!

Tosters have no soles!

Anyway, Byrne had a consortium of governments kidnap the Vision,

wipe his mind and all backups thereof, and take apart his body; by the

time the Avengers rescue him, his personality is unrecoverable, and his

synthetic skin has been so traumatized that it has turned from red to

.

Naturally, this devastates poor Wanda, and she hires a nanny to help

her with Tommy and Billy while she is busy tending to the Vision

during his reconstruction.

She ends up hiring a whole series of nannies, in fact, because they

keep reporting that Tommy and Billy have disappeared, yet when

Wanda returns in a panic, the boys are always right where they’re

supposed to be—so she gets furious and replaces the

nanny in question, only for the same thing to happen with the next

one.

Eventually Agatha Harkness arrives—she’d been killed

by Englehart, but Byrne didn’t let a little thing like that stand

in his way—and reveals that Wanda’s children are

figments of her imagination, given temporary form by her hex

power.

Discovering that she’s crazy drives Wanda even crazier: first

she goes catatonic, then she reunites with her father Magneto and

her brother Pietro to form sixty percent of the old Brotherhood of Evil

Mutants.

Back to the basics!

And then, like Englehart before him, Byrne found that the editors were

,

rescinding permission to do his proposed storylines when the

beginning and middle of those storylines had already been

published, prompting him to quit before resolving anything.

Byrne maintains that he’d made sure there were ways to undo his

changes: for instance, if and when the time came to reset the Vision

to his 1983 self, Avengers #238 could be

cited as a point at which his mind had been backed up on Saturn’s

moon Titan, far out of the reach of Earth’s governments.

But no one went back to that save point.

Instead, a series of other writers spent the next fifteen years or so

doing a slow-motion replay of the Vision and Wanda’s initial

development.

The Vision is returned to a red body and gradually regains his

emotions.

Wanda is depowered, then can cast unpredictable hexes, then returns to

Agatha Harkness and learns to wield chaos magic.

By 2003 Wanda and the Vision are starting to spend some time

together.

And then Avengers was handed to Brian

Bendis.

I wrote about

Bendis’s run on Avengers (and its

multiple spinoff books) while it was happening.

My main focus was the “Avengers

Disassembled” storyline that kicked off his

tenure.

It was very bad.

My summary was “talk talk talk chaotic

violence chaotic violence talk talk talk talk talk talk talk

talk chaotic violence talk talk talk talk talk

talk talk talk chaotic violence talk talk

inexplicable stupidity the end”.

But let’s put the evaluation aside and have a look at the

content.

John Byrne had asserted that Wanda’s ’80s-era power

set—i.e., altering probabilities—required

that she be able to change the past.

For instance, for a building to collapse when she points at it, she

must be retroactively changing the accumulated history of stresses

upon the frame so that every piece of it just so happens to suffer

spontaneous catastrophic failure at that moment.

That would make her a cosmic-level powerhouse, able to warp time

and reality on a scale that would bring her to the attention of a

classic Avengers villain, who had first appeared way back in issue

#10: Immortus, Master of Time!

I’m not sure that Byrne’s conclusions necessarily follow

from the contemporaneous premise of Wanda’s powers, which were

set forth in The Official Handbook of the Marvel

Universe #9: that she could cause “a disturbance

in the molecular-level probability field surrounding the target”

she pointed at.

It seems like Byrne is positing a deterministic universe (e.g., the

likelihood of the building collapsing is either zero or one, and could

be known with a complete knowledge of the history of every particle

in the cosmos, and thus that must be what Wanda’s changing),

while the OHOTMU suggests that in the Marvel

Universe there is true randomness from moment to moment: that the

likelihood of the building collapsing is not zero but something

like 1×10–99, and she’s

upping that until it becomes so likely that it actually happens.

But in any case, for Bendis the takeaway was that Wanda is a reality

warper of immense power.

Or at least, that was one takeaway.

The other takeaway was that Wanda was actually just as crazy as

she’d been at the end of Byrne’s run and had just been

hiding it for fifteen years of real time.

He also took it as gospel that Agatha Harkness had, as she says in

Avengers West Coast #52, made her forget

the existence of her children, and indeed had “closed that corner

of her mind for all time”—even though by #75, Wanda

had recovered her memories of them.

And Bendis wanted to radically change the Avengers lineup to kick out

the sorts of characters he didn’t know how to write and bring in

those he felt more comfortable with (Spider-Man,

Spider‑Woman, Luke Cage, Wolverine).

And so he set forth a story in which the Wasp inadvertently reminds

Wanda that she had once had children; again, Wanda had demonstrated

that she remembered them as far back as 1991, but under Bendis’s

pen, this reminder causes Wanda to become psychologically

unmoored.

She secretly starts warping reality in ways that go far beyond her

usual “gun jams” and “machine blows up” tricks:

zombie versions of dead Avengers show up and explode, a fleet of alien

spaceships launches an attack, and in a scene that kind of sums up the

storyline, the Vision flies a quinjet directly into Avengers Mansion

9/11‑style, emerges from the wreckage, spits out a bunch of

spheres that turn into an army of Ultrons, and is then ripped in half

by a berserk She‑Hulk.

While a few dozen Avengers stand around barking Bendis dialogue at each

other, Doctor Strange shows up, gives them all an issue-long lecture,

and then leads them to a bubble of false reality where Wanda has holed

up with replicas of loved ones she has conjured up: the old Vision,

their two boys (now age ten or so), Agatha Harkness.

Bendis can’t write superhero fights that go beyond

“overpowered hero zaps villain”, so he just has Doctor

Strange zap Wanda and that is pretty much that.

And, I mean, given that (as

I once documented) the recurring gimmick of early issues of

The Avengers was that the hapless Avengers are

bailed out by outside help, I guess Bendis was sticking to those

established motifs.

So the Vision and the Scarlet Witch were off the board for a

while.

Of course, in comics no one stays dead—even in cases like

Ben Parker and Gwen Stacy, there’s always an alternate universe

or six out there that has its own book that allows you to follow their

ongoing adventures.

So not only was the Vision eventually brought back and the Scarlet

Witch rehabilitated, but Allan Heinberg even imported young adult

versions of Tommy and Billy from parallel universes to serve as key

members of his “Young Avengers” spinoff team.

Tom King wrote a critically acclaimed twelve-issue series called

The Vision in which the Vision builds himself

a synthezoid family: wife, son, daughter, even a dog called

Sparky.

And Steve Orlando has taken a few swings at keeping a Scarlet

Witch series running.

But c’mon.

We know the drill.

As far as the Marvel Cinematic Universe is concerned, Brian Bendis

is Homer, Shakespeare, and Stan Lee all wrapped up in one.

So when, in a pleasant surprise, the MCU folks decided to devote an

entire show to the Vision and the Scarlet Witch, naturally they

were going to see what Bendis had done with them, even though the answer

was that he had written them out of the series immediately because

they are not

.

That didn’t stop the WandaVision team

from building their series around the handful of pages Bendis had given

those two characters, but it meant they had to bring in some other

material as well.

And the main thing they brought in was my favorite movie!

spoilers start

spoilers start

here

I don’t know how WandaVision was

advertised; for all I know, everyone else who watched it went in

already knowing the premise.

But the creators were brave enough not to start with a framing

sequence that would give away what they’re up to.

I went in having spent four years avoiding spoilers, so I was

expecting something that would pick up from where the

Avengers movies had left off.

Instead—well, as many have pointed out, one of the

successes of the MCU is that it has slotted its offerings into

a wide variety of genres.

On the TV side, for instance, Jessica Jones is

a film noir private eye procedural, Luke Cage

is ’70s blaxploitation, Runaways is a

superhero version of The Breakfast Club, and

The Punisher is part of that post‑9/11

genre that Jon Bois memorably described as “a quasi-apocalyptic

nightmare that reduced America to a cathedral of death

worship”.

And WandaVision kicks off looking for all the

world like an 1950s sitcom à la I Married

Joan.

Black and white, squarish aspect ratio, old-fashioned theme song,

old-fashioned jokes, old-fashioned situations: in this one, the

Vision’s boss from down at the data processing office is

coming over for dinner and our star couple needs to impress him

(and not give away that they have superpowers).

There are a few signs that things aren’t what they

seem—for one thing, the town seems more ethnically

diverse than we might expect for a ’50s sitcom, though initially

that seems like it might just be a concession to the fact that by

2021 a little anachronism was considered a worthwhile price to pay

for a more inclusive cast.

More tellingly, our attention is drawn to weird gaps in the

characters’ knowledge of who they are and how they got

here—and we zoom out at the end to show the closing

credits playing on a monitor in modern times.

But the creators courageously bet that viewers will tune back in with

no explanation beyond that.

And while episode two gives us an animated title sequence that shows

we’ve progressed to the Bewitched era,

it otherwise seems like more of the same.

At least for seven minutes.

But then Wanda discovers that a toy helicopter has fallen into her

hedge.

And it’s in full color, even as the hedge, Wanda herself, and

the rest of the world around her remain in black and white.

Eeeee!

This is the chief gimmick of

Pleasantville!

In that movie a couple of kids get transported to a ’50s sitcom

where everything is black and white, but their presence starts to push

the culture forward, and little pops of color start to appear in the

monochrome world!

And now the MCU was playing with the same trope—and not

just with any characters, but with two of the characters I most

imprinted on when I was nine, ten, eleven, twelve years old!

Like, I’m looking at what’s coming up next, and, like, I

don’t really care overmuch about the Falcon, or Bucky Barnes, or

fuckin’ Loki—but I absolutely

care about the Vision and the Scarlet Witch.

And here they are in Pleasantville.

It’s like when I watched

Knives Out and boggled at the extent to which it seemed to have

been made specifically for me.

So, yeah, this turns out to be a Pattern 11 story: it starts off by establishing

a false ceiling (the strictures of an old black-and-white sitcom) and

then bursts through it.

Because it turns out that we’re in the MCU after all, and what

we’re seeing is all part of the creators’ bricolage.

Avengers: Infinity War had established

Wanda and the Vision as a couple, but before that movie was over, the

Vision had been violently deactivated by Thanos, and Wanda was one of

the characters who had succumbed to the Thanos snap.

WandaVision eventually fills in the gap between

Wanda’s return at the end of Avengers:

Endgame and the 1950s sitcom: we learn that the Vision’s

body had fallen into the custody of a S.H.I.E.L.D.-adjacent

organization called

Wanda had stormed in and discovered S.W.O.R.D. technicians busily

dismantling the Vision in a scene

to the ending of Byrne’s West Coast

Avengers #43.

But instead of taking the body back with her, à la

WCA #44, Wanda retreats to the New Jersey

town where the Vision had proposed that they settle down, and in her

grief, turns it into a bubble reality—much like the one

Bendis had her create in Avengers #503,

complete with a Vision forged from her memories.

The twist from outside the comics is that the creators of the TV

show—being TV people rather than comics

people—establish that, as a little girl in Eastern

Europe, MCU Wanda had been fixated on DVDs of American sitcoms her

father had smuggled in, running the gamut from The

Dick Van Dyke Show to Malcolm in the

Middle, and that these influence the shape her bubble reality

takes.

For WandaVision is also a

Pattern 43 story,

television about television.

Normally I consider Pattern 43 a negative, but the way the show

tracks the development of the sitcom through the second half of the

twentieth century, with episodes devoted to re-creating the tropes

of each decade… again, this could hardly be more up my

alley.

So, as in Englehart’s Vizh/Witch series,

Wanda gives birth to Tommy and Billy—but in the ’80s

episode, they age from babies to preschoolers in an instant, just

like the babies from such ’80s sitcoms as

Family Ties, Growing

Pains, and I’m sure many more.

The bricolage continues: the show references the characters of Glamor

and Illusion from that ’80s series, and brings in Sparky the dog

from Tom King’s Vision series of the

2010s.

Tommy and Billy gain powers as in Young

Avengers.

Pietro shows up—played not by the actor who played him

in the (Disney) Avengers movies, but the

one who played him in the (Fox) X‑Men

movies; one of the S.W.O.R.D. agents monitoring the bubble reality

makes this into an

on recasting.

The white Vision makes an appearance.

And Agatha Harkness turns out to play a significant role, though the

show changes her look significantly—I guess Maggie Smith

was booked.

WandaVision also gives significant

to a couple of characters rarely linked to the Vision or the

Scarlet Witch.

One is Jimmy Woo from the Atlas Comics era, who seems to have been

tapped as the Agent Phil of this phase of the MCU.

The other is the second Captain Marvel—Carol Danvers,

the one featured in the Captain

Marvel movie, is the fifth or sixth, depending on whom you

count.

The first was Mar‑Vell of the Kree, whom Jim Starlin had

succumb to cancer in Marvel’s first graphic novel, back in

1982.

Later that same year, Roger Stern introduced Monica Rambeau, a new,

completely unrelated character who adopted the same

name—gotta keep those trademarks active!—and

had her join the Avengers in his very first issue on that title.

Her tenure (#227 to #294) did overlap with the return of the Scarlet

Witch (who rejoined the team from #235 to #255) and the Vision (#242 to

#255), but otherwise she’s never really been in the same orbit as

those two, so it’s a bit odd for her to play such a prominent

role here.

But my understanding is that she’s returning at some point

and so she’s here not just as a S.W.O.R.D. operative but to get

powered up in preparation for her next appearance.

And, y’know, just to get some screen time so that she might

mean something to people who didn’t already know her from

the comics when she does reappear.

Because that’s one of the things that making a TV show about

TV highlights: television adds up.

Back in the era when the WandaVision

sitcoms are set, watching a sitcom meant visiting its cast of

characters twenty-two times a year.

That was a big part of what sitcoms offered, apart from the laughs:

spend half an hour hanging out with your old friends!

And, during that same era, much the same was true for comics.

See, I thought this was great.

Nothing in the MCU has come close to that first Iron Man movie that

kicked off the whole shebang, but I liked

WandaVision more than any MCU offering from

2009 to 2020.

But like I said, this show draws from my corner

of the Marvel Universe.

Again, I see that coming up I have MCU offerings featuring the Black

Widow, Shang Chi, the Eternals… and, sure, I know who they all

are.

But the amount of time I spent over the course of my childhood

(and have spent since!) reading comics featuring the Vision and the

Scarlet Witch in particular would be measured not in hours but in days,

maybe even weeks.

To have them starring in a twist on

Pleasantville was a delight, to me.

But to someone who only knows them from the MCU?

How much screen time did these characters get in the movies leading up

to this series?

Two minutes here, three minutes there?

The MCU is made up almost wholly of events: individual movies and

short series, with most of the latter releasing every episode at

once.

Only Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. had traditional

orders of twenty-two episodes a season, starting in September and

showing one episode a week, with short breaks, until May, year after

year.

Not surprisingly, it was also the only one of these shows that,

near the end, traded on the idea that the audience might have bonded

with the characters over the course of years of watching them on

a regular rather than sporadic basis.

WandaVision couldn’t do the

same—except for people like me who’d already bonded

with them.

I mean… when I was nine, I brought along a stack of comics with

the Vision and Scarlet Witch in them to the week-long outdoor ed

program that sixth-graders in my district went to.

As I lay in my bunk in that cabin up near Big Bear back in 1983,

rereading those (already slightly battered) comics for the fifth

time, little did I suspect that I’d be watching a live-action

version in 4K resolution four decades later.

And I doubt I would have enjoyed the show so much if those comics,

now yellowed with age, hadn’t been sitting in boxes inches

behind my head as I watched.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

|

comment on

Tumblr |

reply via

email |

support

this site |

return to the

Calendar page |

|

|

|

|