[Stan Lee, John Romita Sr., Devin Grayson, J. G. Jones, Roy Thomas, John Buscema, Ralph Macchio, George Pérez, David Michelinie,] Eric Pearson, Jac Schaeffer, Ned Benson, and Cate Shortland, 2021

As I have noted in recent articles, even after Marvel brought back Captain America in 1964, he mostly continued to be pitted against Nazis or Nazi-adjacent organizations. Though the Cold War was close to one of its zeniths—1964 was the year of both Fail Safe and Dr. Strangelove—it was surprisingly rare for Cap to find himself fighting villains from the communist world. The same could not be said for Iron Man. At this point he was the headliner of a comic called Tales of Suspense, and in Tales of Suspense #50, cover date 1964.02, he takes on the Mandarin, who hails from what is described as “seething, smoldering, secretive Red China”. In issue #51, he takes on the Scarecrow, who steals some of Tony Stark’s designs for new weapons in order to smuggle them to Fidel Castro’s Cuba. Then, in Tales of Suspense #52, Iron Man takes on a couple of Russkies. As a sign of how seriously Stan Lee and co-writer Don Rico took this story, they cribbed from Bullwinkle and named the villains Boris and Natasha. Boris would only appear in two other comics. Natasha would appear in, as of this writing, 1330 more. She’s the Black Widow.

In this first appearance, you might be excused for thinking that she was called “the Regular Widow”, as the creators put her in a veil as if she were heading for a funeral. But her dress is not black but bright green, so it’s not that—rather, a half-veil had once been a sign of glamor. Marlene Dietrich often wore one, for instance. Of course, by 1964 this look had been outmoded for quite a while, suggesting that Natasha is being put forward as a sophisticate of a certain maturity. And the creators load her up with other markers of the pre-war aristocracy: a fur coat, evening gloves, lots of jewelry, and by the next issue, one of those long F.D.R. cigarette holders and a star-shaped beauty patch near her eye like the ones Clara Bow used to wear. This is not a supervillain costume of the sort that Electro was wearing over in Amazing Spider-Man that same month, because the Black Widow isn’t a supervillain—she’s a spy. Here’s the story. In Tales of Suspense #46, Tony Stark, as Iron Man, had tricked top Soviet scientist Anton Vanko, who wore his own suit of armor as the Crimson Dynamo, into defecting to the U.S. and working at Stark Industries. Nikita Khrushchev (who appears on panel) summons Boris and Natasha to kill Vanko, Stark, and Iron Man (because in the comics the public didn’t know that Stark was Iron Man until 2006). They do this by walking into the lobby of Stark Industries, asking to see the head of the company, and sauntering into his office without even telling Stark’s secretary who they are. “Wait! Whom shall I say is calling?” “Do not bother! I shall introduce myself!” The woman in the half-veil promptly does so, introducing herself as “Madame Natasha”. With this name and aristocratic garb, you can probably guess where this is going. She will explain that she is the daughter of White Russian émigrés, dedicated to using her family’s vast fortune to drive the Bolsheviks out of her ancestral homeland, and propose some joint ventures with Stark to achieve this end. Perhaps the plan is to marry Stark before killing him, living up to her code name. But no—she says that she and Boris are from the Soviet Union and would like to see Stark’s munitions plant because Boris is a science teacher and would find it interesting. Stark, thinking “What a beauty she is!”, replies that “I’ll be glad to show you around personally!” “Minutes later”, according to the caption box, Stark changes the plan: “You’re much too lovely to spend all day touring a dull factory! Suppose we let Boris continue the tour himself while we have dinner together?” So, while Stark and “Madame Natasha” are “at a swank supper club”, Boris, left to his own devices, blows the plant up. It’s that trademark Tony Stark genius in action!

Anyway, while Iron Man is fighting Boris, Natasha tricks the armored Avenger into turning his back so that Boris can deal a critical blow: “A… a jet of water on my back!! Boris… he’s short-circuiting me!” (I guess at this point Iron Man’s armor is basically a red and yellow Cybertruck.) “Gullible fool! It worked!” Natasha crows. But Vanko sacrifices himself to save the day; he and Boris are killed. Natasha makes her escape, however, and the next issue, she’s back—now with black hair instead of brown—and lands another appointment with Stark. “It is so good of you to see me!… I feel so ashamed… to think I once tried to harm you…” she sniffles. “There, there!” Stark replies. “I don’t make a practice of harboring grudges!” He shows her an anti-gravity device he had invented, at which point Natasha sets off a gas grenade she’d been keeping in her purse and steals it. She spends the rest of the issue using the device to destroy Stark’s factories, but when the issue is almost over, Stan has Iron Man randomly discover a way to disable the device. “This proton electric charge will destroy the output of the ray forever!!” Natasha gets away again, and the cops grumble to Iron Man: “Imagine Stark allowing that weapon to be stolen! If you ask me, he’s just an overrated playboy… or worse!” “It’s a good thing he has you around to correct his bumbling mistakes!”

With Boris gone, Natasha needs a new stooge, and in Tales of Suspense #57 she finds one in a new would-be superhero: “Hawkeye, the marksman!!” In his first outing he tries to stop a bank robbery, but the cops think he’s the robber, and soon have him on the run. Natasha, driving by, thinks that “he might be what I’m looking for!” and offers him a lift. Hawkeye is so instantly smitten by her that when she proposes that “you might be the very ally I’ve been seeking!”, he replies, “Whatever you’re lookin’ for, gorgeous, you can bet your bottom dollar… I’m it!” She loads Hawkeye up with a bunch of arrows loaded with technological gizmos provided by her “communist masters”—though she keeps that last part to herself, thinking, “I will be able to twist him around my little finger! But he must not learn that I am really a red spy!” She sics him on Iron Man, but when Hawkeye tries to nail him with a “demolition blast” arrow, “the strongest, most skillfully made flexible iron armor in existence, tempered to the highest degree of resiliency ever attained by any metal” shrugs off the explosion. But, whoops, Natasha is standing too close to the blast and gets knocked out! Hawkeye freaks out and tries to rush her to safety, screaming, “She has to live!! She has to be mine!! She’s the only one I’ve ever loved!!”Anyway, she’s fine, and in #60, she hears that Stark has gone missing and decides to send Hawkeye in to “steal the plans for the latest weapons!” Hawkeye is dubious: “I have agreed to be your ally, my lovely Black Widow… but my heart rebels at the thought of treason!” “It will not be treason, my bold hero!” Natasha replies. “I only serve the cause of international peace!” (In that same panel, she thinks, “He believes any lie I tell him!”) Natasha’s plan turns out to be a bust, because, as his secretary explains, “Mr. Stark keeps all his secret formulae in his head! He doesn’t dare trust them to safes!” Still, Hawkeye makes a clean getaway. The same cannot be said for Natasha, who is rounded up by the Soviets. She’s afraid that she is soon to have a date with an open window, but instead Khrushchev has her retrained for a new role, which is an in-universe way of saying that Stan and company had realized that the eight-year-old boys buying Marvel comics didn’t want to read about a character who was explicitly described in the stories as a knockoff of Mata Hari, of whom they’d probably never heard. They wanted to see super-people battling it out! Spider-Man was popular, and here was another character who happened to be named after a spider. So in Tales of Suspense #64, cover date 1965.04, the Black Widow returns as, essentially, Spider-Woman, with the same powers: clinging to things (with special boots), swinging around town on a rope (that shoots from her gauntlets), and even wearing a costume with a webbing pattern on it, though on her it looks like fishnets. As that pop-up panel suggests, she’s still fighting Iron Man, and she’s still ordering a lovesick Hawkeye around…

…but the following month, Hawkeye would join the Avengers with Iron Man’s endorsement. He explains that the Black Widow had been shot by “the communists” and taken away. We learn in Avengers #29, cover date 1966.06, that with Khrushchev having been deposed, the Widow is now working not for the Soviets but for the Chinese. (Her costume is changed to actually involve a lot of fishnets over bare skin, but this will be changed back the following issue.) She is now backed up by not just one goon but two, the Swordsman and Power Man, and tries to recruit Hawkeye, but he declares that “who challenges the Avengers, challenges Hawkeye!” and refuses to join her side. Still, after the Widow and her partners are defeated (primarily by the Wasp, who earlier in the issues had spent a full page being menaced by a sparrow), Hawkeye cannot bring himself to prevent her escape. A dejected Hawkeye tells Captain America to start his lecture, but Cap replies, “There’s nothing to say, fella! We’re all Avengers, yes… but we’re also human beings, with feelings, and emotions!” (As if we needed any more proof that Captain America is a liberal.)

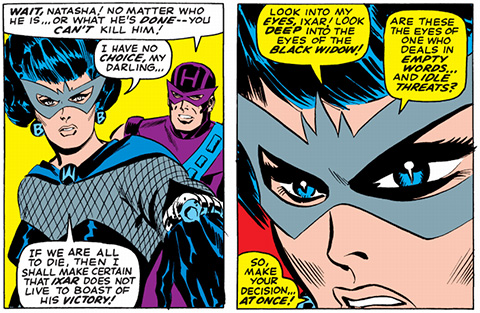

In the following issue, Natasha switches sides again, saying that the brainwashing the Maoists had put her through had worn off. She would stay in the Avengers’ orbit for over a year. She doesn’t officially join the team—Hawkeye nominates her for membership, but Hank Pym vetoes the idea, saying, “As one of the original Avengers, I don’t care too [sic] see it turn into a rest home for reformed super-villains!” But she does hang around as Hawkeye’s ladyfriend, and occasionally joins the team on missions. In Avengers #37, the fact that she is not an Avenger ends up saving the day, as she is able to scare off an alien warlord who hadn’t taken the actual Avengers seriously:

That kind of ruthlessness puts her on Nick Fury’s radar as a potential recruit, and he presents her with a proposition: she’s not a superhero but a spy, so if she has indeed reformed, her true place is not with the Avengers but with S.H.I.E.L.D., the Marvel Universe’s top spy agency. Natasha signs up on the spot, which leads to a period of uncertainty about her loyalties: she disappears with little explanation and seems to be working with the Chinese again, so is she operating as a double agent on S.H.I.E.L.D.’s behalf? Or is she a triple agent who actually has returned to villainy? (The Black Widow of the Ultimate Universe does turn out to be a villainous traitor, after all.) Eventually the Avengers writer of this era, Roy Thomas, gets around to establishing an origin for the Widow. We learn that the Natasha was married to a Soviet test pilot named Alexi [sic]. When the authorities drop by her apartment to inform her that her husband has been killed in an accident, Natasha said that she wanted to “do something to be worthy of his memory”, so the Soviet government trained her to be a spy. But her husband is not actually dead: the accident was a cover story. In reality, Alexi had been put into a program that aimed to develop a Soviet counterpart to Captain America, which turned him into the Red Guardian. Hawkeye is pretty bummed when he journeys “behind the Bamboo Curtain” to rescue Natasha, only to find out that she’s married, that her husband is still alive, and that both of them are working for the communists, as Colonel Ling’s “advanced polygraph” shows that the Widow is genuinely loyal to them. She isn’t—S.H.I.E.L.D. had loaded her up with psychic defenses so she could infiltrate the enemy camp and sabotage their doomsday device—and the Red Guardian sacrifices himself to save her when she reveals her true purpose and Ling tries to kill her. So Alexi’s out of the picture. Still, this is the beginning of the end for the Hawkeye/Widow romance, as Natasha appears only sporadically for the rest of the ’60s, ostensibly because she’s always off on S.H.I.E.L.D. missions we don’t get to hear about. And Hawkeye is always busy with the Avengers—when he grumbles that his duties are interfering with his love life, Natasha retorts, “What love life? It’s been weeks since we even had dinner together!” Still, it is quite abrupt when, in Avengers #76 (cover date 1970.05), the Black Widow shows up at Avengers mansion—her first appearance in a Marvel comic in a full year—and announces that she’s leaving forever… and it’s not just a plot point.

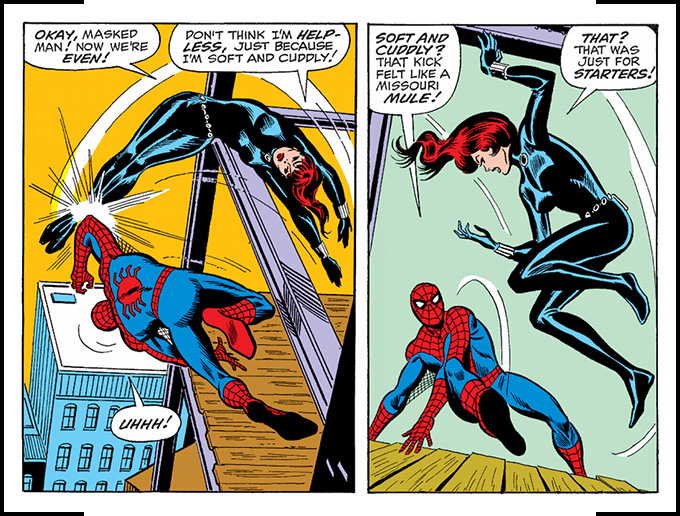

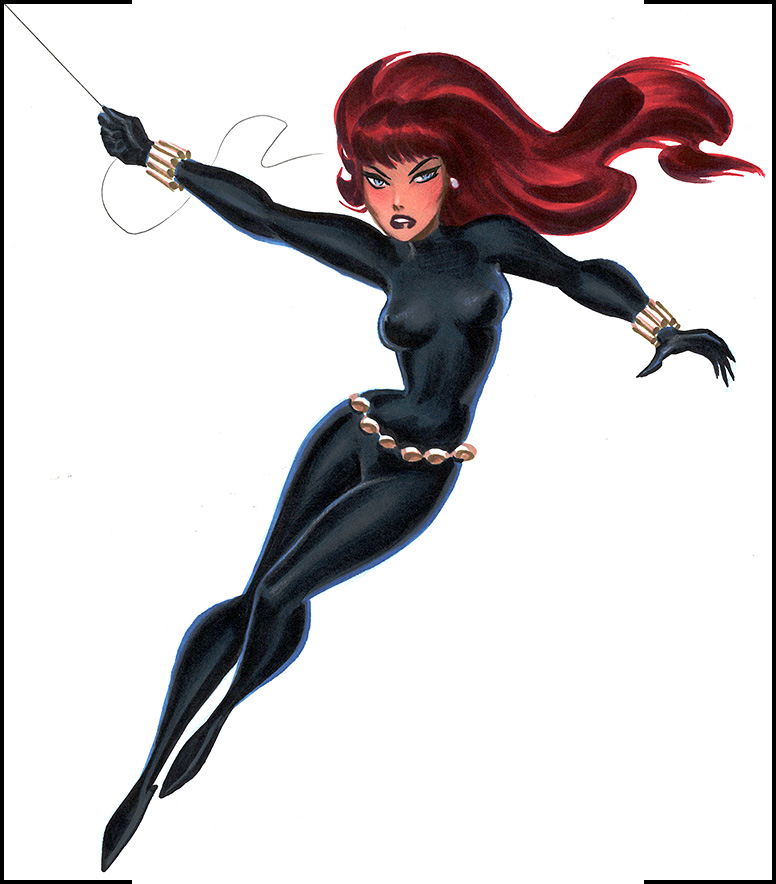

For two months later, over in Amazing Spider-Man #86—still written by Stan, this late in the game!—John Romita Sr., whose appealing art had made Gwen Stacy and Mary Jane Watson nearly as much a part of the Marvel brand as the superheroes were, debuted a total reinvention of the Black Widow’s look. Out went the mask, the fishnet patterns, the jewelry bearing big B’s and W’s, and the bob of black hair. In came a slinky, skintight catsuit and—out of nowhere, and unexplained—a glorious mane of bright red. “It may not be as fancy, but this new costume will be more in keeping with the swingy Seventies!” Natasha reflects. And it wasn’t only the opportunity to have Romita be the one to create the model for later artists to follow that led to the Widow’s new look premiering in Amazing Spider-Man—the cover has Spider-Man declare “She’s a female copy of myself!”, and the creators double down on the notion that, yeah, her power set will be nearly identical to that of their flagship character. (As J. Jonah Jameson puts it, “It isn’t the wall-crawler! It’s a girl—copping his act!”) The flimsy story of the issue is that the Widow decides to fight Spider-Man “to see what makes him tick!” so that she can “use it… for the benefit of… the new Black Widow!” A sample: