…though this is less a “2024.04 minutiae” than an “I’ve had these items sitting around for months now and might as well just publish them rather than waiting to slip them into a more substantial compilation of minutiae”.

From January:

Okay, you all read the sign. If you want service, you must wear a shirt, you must wear shoes, and you must shout “FUCK!” at least three times before the end of the tour.

From September:

“Do I really need to wear a shirt on the tour?”

“If the management requires you to wear a shirt on the tour, you may need to wear a shirt.”

When I was in college, one of my roommate’s prized possessions was a copy of a book called The Cuckoo’s Egg (1989), in which author Clifford Stoll describes how he had tracked down a KGB hacker while employed at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. The book was signed by the author, but not as part of an official signing: Stoll had found his own book on the shelf at Cody’s, signed it (along with the exclamation “GADZOOKS!”), and put it back as a surprise for whomever ended up buying the book, and that turned out to be my roommate. Stoll later wrote a book called Silicon Snake Oil (1995), in which he dismissed the Internet as a passing fad, citing online shopping in particular as a bunch of hype that would pan out about as well as cold fusion or Esperanto. Never in a million years would people buy products off a web site, he contended, because no one is going to spend money to buy an item they’ve never held in their hand, never even seen with their own eyes.

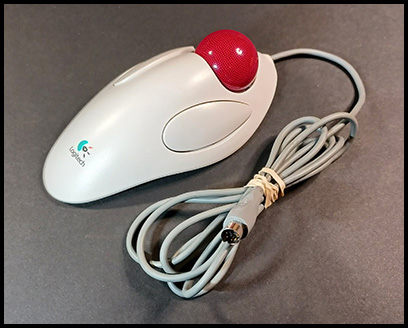

So for well over twenty years now I have used Logitech Marble trackballs as the pointing device on all my computers. The first one I got looked like this:

Subsequent models have had different color schemes and switched from PS2 to USB connectors, but the shape has remained consistent. I have a couple still in service. Recently I accidentally knocked one onto the floor, and when I picked it up, it acted wonky for a bit. Annoyed, I hopped online to pull up my most recent order from back in 2019 and click the “Buy it again” button—only to discover that the price had spiked from $20.88 to $219.95. So, no new trackball for me. It turned out that Logitech had discontinued all their non-thumb trackballs and these were the last few that third-party sellers had in their inventory. Dispirited, I pulled up some reviews to see what the best replacement might be. There was no consensus, and the leading contenders all had significantly different shapes. I had no idea which would feel like the most natural way for me to click around on my computer, i.e., to engage in the activity I spend hours doing every day. Now, there used to be an easy solution to this quandary: go to the trackball aisle of CompUSA and try them all out. That’s what I did to settle on the Logitech Marble in the first place, after all. Even at the time I bought this most recent one, I could have gone to Fry’s Electronics to test out alternatives. But now, if any of those sorts of stores are left, I don’t know where they might be. The closest thing I can think of is Best Buy, which sells two trackballs, both of which are thumb ones, and I don’t even know whether Best Buy has display models of either one—I doubt it.

So, yeah, it’s easy to mock Stoll for being so wrong that he thought people would never buy products online when now there are whole ranges of products that you can pretty much only buy online. But his argument was that e-commerce would never get off the ground because people would always want to physically inspect the items they were thinking of buying. What he seems not to have taken into account is that real vs. online shopping wasn’t an either/or proposition—that people could drop by brick-and-mortar stores, do their in-person inspection of the merchandise to verify that it was in fact what they wanted, and then go home and order it on Amazon. Except maybe, over the long term, it is an either/or, as the aforementioned practice has led many brick-and-mortar stores to go out of business. And maybe if people living in the “go to Fry’s, see which trackball you like, buy it” world had been given the option either to stay there or jump straight into the world where acquiring most items means deciding between products by such trusted outfits as LERGNA and SWOMMOLY with nothing to go on other than ChatGPT reviews posted by bots, they might indeed have elected to stay put. But that period of overlap was just long enough to have routed us into the future we wouldn’t have chosen.

One of the canards right-wing pundits, and the misinformed, trot out against progressive taxation is that people will work less for fear of moving into a higher tax bracket. E.g., the California state income tax for single filers is 6% for income over $38,959 and 8% for income over $54,081. “So if I’m making $54,081, why should I want to earn that extra dollar? I’ll suddenly be paying a third more in taxes—that’ll more than cancel out my gains!” But that’s not how it works. It is not the case that the tax on $54,081 is $3244.86 and the tax on $54,082 is $4326.56. Only the extra dollar is taxed at the higher rate. The tax on $54,081 is actually $1763.76. The tax on $54,082 is $1763.84. Unfortunately, in some cases Obamacare does work the way the pundits suggest.

Since the U.S. apparently can’t find it within itself to act like virtually every other developed country and just supply health care or at least health insurance via tax revenue, we have this weird Rube Goldberg machine (which is better than what we had before, which was nothing). You submit a projected income to the government, which adjusts those projections based on recent tax stubs, salary offer letters, and the like. Based on that projected income, the government offers a subsidy to help pay the premiums on a plan purchased through an online health exchange. If your income exceeds the projection, you have to pay back the difference between your actual subsidy and what your subsidy would have been had the projection been accurate. However, the payback amount is capped at different levels based on income. Up to 200% of the federal poverty line, the payback cap is $350; if your income at least 200% but less than 300% of the poverty line, the cap is $900; from there to 400%, it’s $1500; and at 400% of the poverty line, the cap disappears and the full difference is due. What does that mean if you’re currently getting your premium fully paid by the subsidy? I coded up a program to do the calculations, and here’s what it came up with:

The x-axis represents gross income from $0 to $100,000; the y-axis represents gross income minus the Obamacare payback amount. The larger sawtooth there represents the tax bite caused by the removal of the payback cap at 400% of the federal poverty line—for individuals in 2023, that meant $54,360. The top of the sawtooth represents the point at which you’re better off not making that one extra dollar. Specifically, if you made $54,359 in 2023, then after the Obamacare payback, your net income was $52,859… but if you made $54,360, then your net income was $49,740. You would need to get up to $57,770 to get back into positive territory—and at that point, you could update George Harrison’s lyric to “Let me tell you how it will be / There’s one for you, four thousand nine hundred ten for me”.

I first encountered Tom Lehrer watching The Electric Company as a small child, though not by name—it wasn’t until many years later that I learned that he was responsible for two of the most memorable cartoons on the show. I think I also encountered his song about the elements in a class before I ever heard his name. But in high school I discovered Dr. Demento’s radio show; he made sure to credit the creators of the songs he played, and Tom Lehrer’s name popped up quite a bit. At one point he played the entirety of An Evening Wasted with Tom Lehrer, and I taped it, so I know those eleven songs far better than the rest of Lehrer’s oeuvre. The album kicks off with “Poisoning Pigeons in the Park”, in which Lehrer sets an account of his protagonists’ avian murder spree to a jaunty tune: “When they see us coming, the birdies all try and hide / But they still go for peanuts when coated with cyanide…”

One class in my AP Literature curriculum back when I taught in a public school was about comedy—specifically about the jokes in Hamlet, but also about what makes things funny more generally. What makes us laugh? Some of the options I hoped would come up in our discussion each year (and which I planned to throw in if they didn’t) were:

“comic relief”: a respite from a tense or downbeat portion of a narrative

incongruity: as in the “rule of three”, when a pattern is set up and then violated (e.g., a late night host during the social distancing stage of the pandemic saying that what he misses about having a live audience are “the laughs, the energy, and keeping the lost wallets”)

transgression: from “benign violation” of societal norms (e.g., fart jokes) to edgelord humor

recontexualization: e.g., puns

the odds against something: I talk about this in a prior Chuckle Box

associated pleasure / the shock of recognition and belonging: key to in-jokes—I talk about these in this article

power dynamics: the main answer offered up by philosophers from Plato to Hobbes, and key to the jokes in Hamlet, since so many of them are based on the idea that Hamlet, as a prince, can insult the courtier Polonius with impunity

However, I was astonished to find that students generally offered up none of these. I’d ask them to think of something they had found really funny—from a comedian’s routine, from a TV show, from real life, from anywhere—and explain why they thought it was funny. And almost without exception, their answers were that “it was so random”. I flipped through the quickwrites they’d turned in and it was just page after page of “We were eating dinner and my dad kind of half-sneezed and my mom looked confused and looked over at him and said ‘Did you say something about giraffes?’ and my sister and I laughed and laughed because it was so random.” There would also usually be a couple of students in each class who would protest that humor was inherently random—that something either made you laugh or it didn’t, and there was no way to predict whether it would or wouldn’t, so there was no point in analyzing it.

For ages I had thought that “Poisoning Pigeons in the Park”, while funny, was also pretty random. Yes, it was transgressive to write a song about the delights of animal cruelty. Yes, it was incongruous to present killing birds as a pleasant springtime activity, and to pair it with a sprightly melody. But mainly the song was wacky. Poisoning pigeons in the park? What a random thing to do! Except quite recently I learned that it wasn’t wacky or random at all. It turns out that in the 1950s the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service did try to control the pigeon population in Boston parks by feeding the birds corn laced with strychnine. Lehrer’s song was satire. And when I learned this… to me the song was retroactively much funnier! I hadn’t realized it, but the feeling that Lehrer was just making up some wild scenario put a ceiling on how funny I could find the song—and discovering that he’d been commenting on the ghoulishness of an actual government program removed that ceiling. And for a fact I learned in the 2020s to add to the perceived comedic value of a song I’d committed to memory in the 1980s… I mean, when I post a Chuckle Box or include a Chuckle Box-type paragraph in one of my articles, I will often deadpan that “jokes are funnier when you explain them”, the idea being that I am ironically acknowledging that I am ruining the joke by taking it apart. Except that’s really a “ha ha just serious” type of line. Having the reference point of “Poisoning” spelled out for me goes to show that, to me at least, jokes are funnier when you explain them.

|

|

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tumblr |

this site |

Calendar page |

|||