|

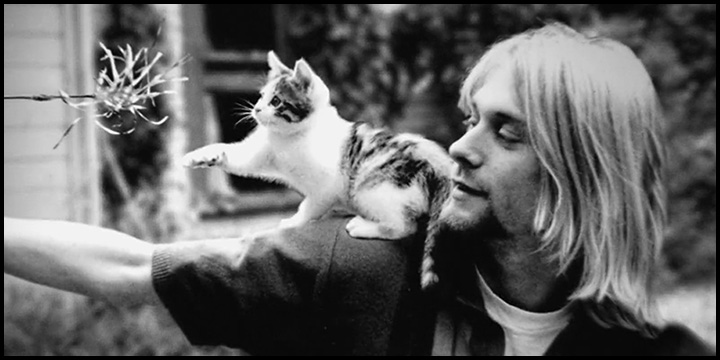

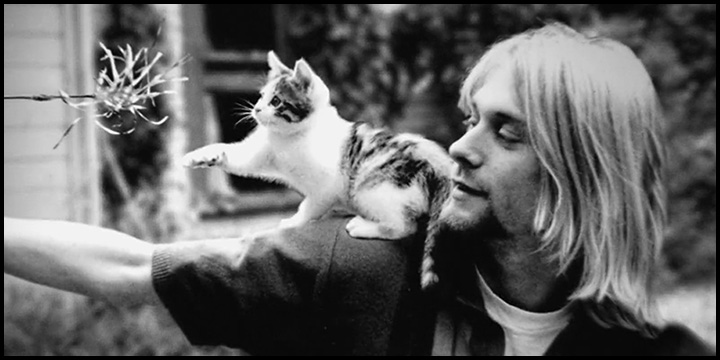

Brett Morgen, 2015 #78, 2015 Skandies Many musicians important to the Baby Boomers died young, but not all of them remained icons when my cohort, Generation X, was in its teens. Buddy Holly? Some nerd whose music might as well have been from the 19th century. Janis Joplin? Some hippie your mom told you about. But Jim Morrison was a crush object to countless Gen X girls, born after he had died. And Jimi Hendrix was still acclaimed as the greatest player ever to pick up a guitar. A generation and a half later, Kurt Cobain maintains a secure spot in the latter group. When I was in high school, I’m sure that most of my peers listened to the hair metal and synth-pop that was popular at the time—because that’s what “popular” means—but pretty much everyone I knew hated it. The coolest kids listened to the stuff they played on college radio, but for the rest of us, the solution was to turn our dials over to the “classic rock” stations and learn about the music of the past. Administrators were perplexed to find that when they set up speakers in the quad to play music at lunch, what echoed across the campus were the sounds of their generation: the Beatles, the Doors, Pink Floyd. These days the music scene is a lot more fragmented, but I’ve found that most of the kids I teach are generally fine with the pop and hip‑hop that rules the charts. But there are still plenty who do end up exploring that “rock” music the kids used to be so nutty about, and Nirvana tends to be one of the first bands they discover. On the flip side, consider this. A few years back I was working an afterschool tutoring session when a student from first period came in. That day she was wearing a Kurt Cobain T‑shirt, which surprised me since she had never spoken about any kind of music other than rap. Again, it wasn’t that Nirvana T‑shirt with the doped-out smiley face, which could just be taken as a token of stoner culture—this was specifically a Kurt Cobain T‑shirt, with his name in big letters above a picture of him playing the guitar. This seemed like a good chance to ask about it. Me: Hey, cool! What’s your favorite Nirvana song? Student: Huh? Me: You’re wearing a Kurt Cobain T‑shirt. Student: [blank look] Me: Nirvana was Kurt Cobain’s band. Student: [looks down] Oh, this? I don’t know who this is, I just liked the shirt. Perhaps this goes to show just how iconic Kurt Cobain has become, that his image has ceased to serve as a representation of an actual human and is just something to wear on a shirt for +3 cool points, like what happened with Che Guevara. But, gadzooks, did that ever make me wish for more hands so that I could go for some kind of quintuple facepalm. Because Kurt Cobain’s music has been deeply important to me. When “Smells Like Teen Spirit” hit the airwaves in 1991, it took me about a week or so before he became my favorite musician, with no close second. And since his suicide in 1994, when talking about, e.g., Jessicka Addams of Jack Off Jill, Julie Christmas of Made Out of Babies, or Care Failure of Die Mannequin, I have always made sure to use phrasings like “my favorite living musician” or “my favorite active band” lest I inadvertently suggest that any of them had displaced Kurt Cobain and Nirvana as my all-time #1. But what does “favorite musician” mean? I remember that once, at a crowded dinner table, my girlfriend at the time said, “Ian Finley is my favorite interactive fiction author,” and when I looked startled, she specified, “I mean, you’re my favorite IF author. But he wrote the IF I like the most.” One of the things I was struck by when I moved from tutoring test prep to teaching high school English was that quite a few of my top students asked me to weigh in on the question of whether you can divorce an artwork from the artist. Ellie says that the Zoomers’ preoccupation with this question reflects the fact that, because we live in an era of identity politics and personal branding, kids feel compelled to define themselves in exhaustive detail, but since we also live under late capitalism, that self-definition has largely been reduced to commodity choices. You are what you consume. “I like this song” thus becomes inextricably mixed up with “I hereby choose a side in whatever web of social media disputes has ensnared this musician”. As for me, I can see it both ways. On the one hand: I just finished banging out a huge chapter in the Photopia book, and doing an initial editing pass, I was struck by just how deeply interwoven every detail is with my own life. The lighting in that scene is just like the lighting in the Andronico’s parking lot on that night in October of 1992! That Usenet post is one I actually read in 1996! That scone she’s eating is one I ate in Connecticut in 2004! I could list several such examples on every page. To suggest that reading this chapter is not an intimate engagement with my autobiography seems absurd. And yet, at the same time, I can listen to a Nirvana song for the thousandth time, still riveted by every note—and feel like my experience has little to do with the life of the guy playing on the track. When I have said that Kurt Cobain is my favorite musician, I haven’t meant that I had any affinity for him as a person. I have just meant that he wrote the music I liked the most. Montage of Heck is not about music. It is a biography of someone who got famous; he could have gotten famous for pretty much anything and you’d still have more or less the same movie. I’ve read enough biographies to have seen that, when they cover figures who have already been written about extensively, they tend to justify their existence either by putting forward new material (“Hey, look at this trove of personal letters that just came to light!”) or particular interpretations (“What really motivated him to run for president was…”). Montage of Heck does both. As an authorized biography, it is able to serve up clips furnished by family members that I, at least, had never seen before: home movies of Kurt Cobain as a young child, footage of newlyweds Kurt Cobain and Courtney Love holed up in an apartment messing around with a camcorder. Material that is less cinematic—notebooks, journals, drawings, cassette tapes—is jazzed up through animation: we see words flow onto lined paper, doodles spring to life, and bits of audio blossom into fully rotoscoped scenes. We also get short interviews with a surprising array of people close to Kurt at various points in his life: both his parents, his sister Kim, his stepmother, his first girlfriend Tracy, Krist Novoselic, Courtney Love… the main person missing is Dave Grohl, but if you want to see Dave, just turn to basically any media outlet whatsoever and wait five minutes. As for what it all adds up to—the movie actually does sketch out a capsule summary of who this guy was. Kurt Cobain’s parents, enmeshed in the culture described in The Feminine Mystique, got married right out of high school and had their first child, Kurt, pretty much immediately. Had he been born in 1947 and grown up in the ’50s, his parents probably would have stayed together even after his mother realized that she was trapped in the empty life of a housewife, having never actually had a chance to discover anything about herself or decide what kind of life she might like to lead. Instead, he was born in 1967 and grew up in the ’70s, and his parents got divorced. Kurt was one of those naturally hyper, rambunctious, destructive little boys—more than one of the people close to me over the years have related how, when they were growing up, there were always those cousins they couldn’t stand because whenever they came over they’d break every toy in the house, and by this movie’s account, Kurt was basically one of those cousins. And so he got shuffled around, not just from Mom to Dad and back to Mom, but to aunts, uncles, grandparents, neighbors. His sister Kim says in the film that he was furious that he didn’t get to grow up in an intact, tranquil, loving household, but that whenever things were going well and the family had settled into a positive dynamic, Kurt would wreck everything, seemingly on purpose. The more he got rejected, the more he would act out, leading to more rejection in a vicious circle. Now, for someone whose music often sounded like it came from a place of bottomless torment, this may not seem like much of an origin story. Oh, so you came from a broken home? Your parents rejected you? You feel unloved and alone? That’s everybody! And yeah—in my generation, at least, that was everybody. There’s a reason that Nirvana’s records sold millions upon millions of copies: we could relate. But we didn’t all respond by plunging into a terminal spiral of self-destruction. Why did he? The central thesis of Montage of Heck is that Kurt Cobain’s fatal flaw was that he could not tolerate even a scintilla of ridicule. Everyone says it—Kim, Krist, Courtney. The slightest hint of mockery or even criticism, and he would fly into a rage or just fall apart, utterly unable to cope with the feeling of humiliation. And so a pretty standard-issue lousy Gen X upbringing, growing up in a redneck town with a mom who went off to find herself and an asshole dad who picked on him, ended up transformed into an irremediable wound that led to heroin addiction and, eventually, suicide. But it also inspired music that dramatically improved my life and millions of others. It occurs to me that one way to answer the question of what “favorite musician” means is to turn to Gottlob Frege’s distinction between sense and reference. Say that your town has an election for mayor coming up, and you don’t know any of the candidates, so you head down to the community center to watch the debate. City councillor Cervino says, “I’ll put in more bike paths!”, and that sounds pretty good to you, so you tell your friends, “I support Cervino! Then, uh‑oh, Cervino gets arrested on a domestic violence charge. Your friends ask how you could support a wife-beater. But while the reference of “Cervino”, i.e., the real entity out in the world indicated by the term, turned out to be to a wife-beater, your sense of “Cervino” was just “candidate who will put in bike paths”. That’s what you supported. Sometimes when people say that they are fans of a creator, it is partially or even primarily their sense of that creator’s public persona they’re responding to—they wish they could hang out. In the case of Kurt Cobain, that doesn’t really strike me as an appealing prospect. Many of those who knew him have suggested that it should be, saying that he wasn’t miserable all the time, but was a sweet soul blessed with otherworldly intelligence, a devastating sense of humor, and a genius for drawing and painting. But for someone who has spent as much time in the spotlight as Kurt Cobain both before and after his death, wouldn’t you think those qualities would be more in evidence? Like, we see a lot of his art in this movie; the drawings are pretty much indistinguishable from what every other stoner kid doodles on the back of his worksheets, and the paintings communicate not much more than “Ooh, anatomy and broken dolls are edgy!” As for the rest of it… I mean, is that where the bar is? Thinking for a moment before you speak makes you a genius for the ages, and some put-downs delivered in a flat sarcastic drawl are the height of comedy? But he absolutely was a genius when it came to putting power chords together. So when I have said “Kurt Cobain is my favorite musician of all time”, I have meant that term in the sense of “the implied intelligence behind these songs”, not as a reference to the real person out in the world who wrote them. Which is a lot of words spent on a point that is now academic. At the end of the 20th century, I would have said with confidence that Kurt Cobain’s place at the top of my personal musical pantheon was unassailable. But over the course of the first decade of the new millennium, others chipped away at that position. In 2002 I got a copy of Clear Hearts Grey Flowers by Jack Off Jill, and within a few weeks it had knocked off Nirvana’s In Utero as my favorite album. In ’09, Die Mannequin’s Fino + Bleed knocked In Utero down to #3, and while it took me a few years to accept, its final track did supplant “Smells Like Teen Spirit” as my favorite song. And as a performer, Julie Christmas, whose band Made Out of Babies I discovered in ’06, at least seemed to me like she may have outdone Kurt in desperate intensity. But none of these bands ended up putting together the body of work that Kurt Cobain did, even though his career was so short. And over the course of the 2010s, the services like Pandora that had introduced me to those bands found nothing new for me. My two favorite albums of 2015 were by Local H and Veruca Salt, whom I’d seen as a double bill way back in 1997! Back in the ’90s I’d turn on KROQ or Live 105, or watch 120 Minutes on MTV, and pretty soon I’d have a long list of new bands to check out; now I would listen to new music for hours on those same stations or on the Internet, and never came away with any new leads at all. Not until the very end of 2019, when I randomly stumbled across a post that introduced me to Moriah Pereira, a.k.a. Poppy. In the summer of 2004 I’d decided to throw together a list of my hundred favorite songs. But in the 2010s, I updated it very sporadically, sometimes not for multiple years. What was the point of shuffling around the same songs? But discovering Poppy meant it was time for an update, and when I wrote up the Poppy concert I went to with Ellie in 2020 January, I was startled to discover what a sea change her music had meant for that chart. Nirvana still had no fewer than three songs just in my top thirty. Poppy now had seven. She had become, I wrote, my favorite active musician. Note the word “active”! Her splashy debut on my chart represented one good album (an understatement: I Disagree had my previous favorites fighting for a distant second), one good EP, and a couple of good singles. But her first EP and first two albums were uneven, and there was still a significant gap between her body of work and Kurt Cobain’s. I noted to myself that Kurt Cobain had killed himself on the 9907th day of his life: 1994, April 5. Almost exactly nine months later, Moriah Pereira was born: 1995, January 1. That meant that she would hit day 9907 on Valentine’s Day of 2022. I made tentative plans to do a check-in on that day to see how their discographies stacked up. But then I started writing up Montage of Heck, and as I went on and on about how Kurt Cobain was my favorite musician, I decided that I probably shouldn’t wait to determine whether that was actually still true. See, Poppy has had a heck of a 2021. She put out fifteen new songs: nine on her new album, Flux, one single (covering a Jack Off Jill song!), and five on an EP called Eat. The last song on Eat, “Dark Dark World”, edged out “Smells Like Teen Spirit” for the #2 spot on my chart. The first song, the title track (which she performed at the Grammys after receiving a nomination for “Bloodmoney”), currently sits at #14. In fact, in my top 28, Poppy currently holds eleven spots. And when you add 2021 to her previous oeuvre, here’s what you get using my music scoring system:

Add it up and that puts Nirvana at 281 points. Throw in posthumous releases such as “You Know You’re Right” and you probably end up around three hundred. Meanwhile, with time to spare before Valentine’s Day, Poppy lands at three hundred and ninety, and that’s without leaked songs such as “Guns & Gold” or “Heavy Metal” that would put her over four hundred. It is no longer particularly close. My favorite musician—not “living” musician, not “active” musician—is Poppy. So henceforth I will be referring to Kurt Cobain as my favorite musician of my youth, and hoping with every fiber of my being that my favorite musician of all time, Moriah Pereira, does not shoot herself in the head.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||