[Steve Englehart, Jim Starlin, Sax Rohmer, Doug Moench, Paul Gulacy, Mark Gruenwald, Ralph Macchio,] Dave Callaham, Andrew Lanham, and Destin Cretton, 2021

I keep starting these articles thinking “this should be pretty short!” and then end up writing 5600 words, or 6500, or 8900. But this one actually will be short. I know virtually nothing about Shang-Chi, and almost everything I do know I already put into my article about Iron Fist. I wrote:

The story behind Iron Fist is very similar to that behind his eventual co-star, Luke Cage. With the arrival of the ’70s, Stan Lee had handed over the creative reins at Marvel over to the next generation. In 1971, Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song and Shaft cleaned up at the box office, “blaxploitation” was all the rage, and Luke Cage was Marvel’s attempt to assimilate it into superhero comics. In 1973, the Bruce Lee vehicle Enter the Dragon one-upped those films, raking in over $400 million worldwide (over $2.3 billion in 2022 dollars) against a budget of $850,000, and reaching #1 in the U.S. at the end of August. But Enter the Dragon was just the headliner of a huge wave of martial arts films that dominated the theaters. It was knocked out of the top spot at the box office by Lady Kung Fu. That movie was in turn replaced at #1 by The Shanghai Killers. Before Enter the Dragon was released in the U.S., five other Hong Kong martial arts films had already spent a week atop the box office in 1973 alone, one of them twice. Enter the Dragon then went on to reclaim the #1 spot in October, preceded by Deadly China Doll. Meanwhile, on the small screen—where, in 1966, Bruce Lee had first brought Asian martial arts to American TV as Kato in The Green Hornet—ABC’s Kung Fu brought in a 20.1 rating, which would have made it an easy #1 in the 21st century. The craze even crossed over into the world of music, as Carl Douglas would soon have a #1 hit in the U.S. and at least fifteen other countries with 1974’s “Kung Fu Fighting”. So it stood to reason that superhero comics, a much more natural fit, would want to get into the act.

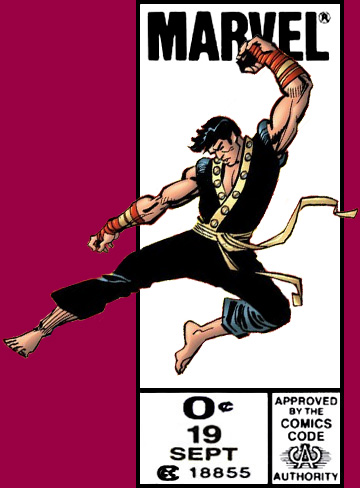

Iron Fist wasn’t Marvel’s first attempt at this. His original appearance was cover-dated May 1974, five months after the debut of Shang‑Chi in a series called Special Marvel Edition which had initially been doing Thor and Sgt. Fury reprints but which soon changed its name to Master of Kung Fu. Shang‑Chi had a few problems, though. First, though he was created by Steve Englehart for Marvel, he was introduced as the son of Fu Manchu, a pulp fiction character from 1912 whose legal status is complicated: Fu Manchu himself is in the public domain in the U.S., but not in Europe, and many characters from his later books are still under copyright protection even here, so Marvel could no longer use them once the licensing deal lapsed. Second—Shang‑Chi wasn’t a superhero! He didn’t wear a costume and didn’t have any powers—though he might have the occasional crossover with Spider‑Man just to sort of show the flag, Shang-Chi was not rubbing shoulders with the Avengers and the X‑Men so much as serving as the flagship character of a little martial arts line, one that would sit alongside Marvel’s western, war, and horror comics. And then, third—not to put too fine a point on it, but when Englehart brought his idea to new editor-in-chief Roy Thomas, Thomas gave him the green light, with one stipulation: Shang‑Chi’s mother would have to be a white American. Marvel wasn’t dedicating a title to a fully Chinese character in 1973.

Shang-Chi went on to star in Master of Kung Fu, which lasted for 125 issues, and Deadly Hands of Kung Fu, which lasted for thirty-three. I’ve never read a single issue of either one. I did finally cross paths with Shang-Chi in 2000, as he appeared in the series Marvel Knights, an attempt to start a team book within the Marvel Knights imprint; I discussed that imprint in my article on the Black Widow, who was one of the members. The others were Daredevil and the Punisher, who like the Widow had their own Marvel Knights books; Dagger (of Cloak and Dagger); and Shang-Chi… and I don’t even really remember his pages. (I bought the book for Dagger.) The first time Shang-Chi made an actual impression on me was in 2018, when Gail Simone brought him into her Domino series; she really built him up, having Domino think, “I mean, keep your Avengers and X‑Men, honestly. This guy is all of everything.” She also has Domino quote Sparks lyrics at Shang-Chi. Gail Simone is great.

The bad guy in this movie is of course Shang-Chi’s dad, though the words “Fu” and “Manchu” are never spoken; instead, he says that he’s been called many names over the thousand years he’s been alive, one of which is Master Khan (an old Iron Fist villain). The reference to “ten rings” in the title also calls to mind the old Iron Man villain, the Mandarin, who wore ten rings on his fingers, each with a different power, any one of which would have made him a formidable opponent. The ten rings in the movie are more like bracelets, and they’re interchangeable. They allow the wearer to do stuff. Pretty much whatever. Stan Lee would approve. “Pretty much whatever” was his favorite superpower!

As for Shang-Chi’s mom, in this version she’s Chinese, though she’s actually from a secret city in a pocket dimension. In the Marvel Universe that would mean K’un Lun, but the MCU already used K’un Lun in Iron Fist so these writers have to check down to Ta‑Lo, which had served as the Chinese counterpart to Asgard for three panels in Thor #301 (cover date 1980.11). Many have observed that each property in the Marvel Cinematic Universe belongs to a different genre, and this emulates one of those movies out of China such as Talking Tiger, Hidden Hatbox or Tyrant = Hero that have people jumping around like they’re in moon gravity and leaves swirling around artfully while those people try to kick each other in the face. But for the sake of the American audience, this Shang‑Chi runs away to San Francisco town when he’s fourteen, and by adulthood has an American accent. There are also some of the MCU’s standard car chases and horde attacks. Neither the Eastern nor Western version of this sort of biff bam pow is my thing, and the personal journeys of the various characters (Shang‑Chi, his sister, his American friend, etc.) were formulaic, so this was a chore to get through.

|

|

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tumblr |

this site |

Calendar page |

|||