Jack Kirby, [Peter Gillis, Bob Harras, Neil Gaiman,] Ryan Firpo, Kaz Firpo, Patrick Burleigh, and Chloé Zhao, 2021

In my article on the first season of Loki, I mentioned that in the 1960s, Stan Lee wrote the first several appearances of every single superhero who received top billing in a Marvel comic book, and Jack Kirby drew the first few appearances of most of them. No surprise, then, that Lee and Kirby are generally credited as co-creators of the Marvel Universe. But were they equal collaborators, or does one deserve more credit? The kool kidz tend to hail Kirby as the real engine that drove Marvel to the top, and some even go so far as to dismiss Lee as a self-promoting huckster who did little more than stick a few speech balloons over work that Kirby and other artists had developed virtually on their own. For instance, that’s how Alan Moore spins it in his 1963 miniseries and in Supreme #62. In the latter, Moore has some throwaway homage characters refer to Kirby as “the source, the fountainhead of all existence” who unleashes “fabulous and seething currents of creative force”. Look at Fantastic Four circa the Beatles’ Rubber Soul era, when Kirby was plotting the book, the argument goes. In rapid succession, the series introduced the Inhumans, the Silver Surfer, Galactus, and the Black Panther, with a quick detour for issue #51, regarded by some as the best issue of the series, which casually tosses in the Radical Cube and the Crossroads of Infinity. But I would argue that what made Fantastic Four groundbreaking was not primarily the cavalcade of ideas; over at DC Comics, the Superman books were already offering up pretty much the same fare. The difference was that Superman was a stiff. All DC’s characters were stiffs. None of them made wisecracks like the ones the Thing made in Fantastic Four. They didn’t bicker and brawl like the Thing and the Torch. They didn’t have problems like Reed losing the F.F.’s operating budget by investing in the wrong stocks. That was what Stan Lee brought to the table. So what happened when he didn’t have Jack Kirby to lean on? Oh, y’know, he just worked with Steve Ditko to create Spider‑Man, who surpassed all of Kirby’s contributions to become Marvel’s flagship character—primarily because of those speech balloons. (When a villain fumes about Spidey dodging his punches, Spidey replies, “I’m sorry to be so uncooperative! I hope I’m not causing you any mental traumas!” DC was not doing dialogue like that in 1964.) Stan without Jack also gets you Doctor Strange, Captain Marvel, Daredevil… even Iron Man, since Kirby’s only contribution to the creation of the character was a sketch of the short-lived gray armor for Don Heck to draw. Meanwhile, Jack without Stan gets you… the Eternals.

“If only we could be like the super heroes in some of these comic magazines, Sue!” Stan has Reed Richards say in that issue I mentioned with the bad stock picks (Fantastic Four #9, cover date 1962.12). “They never seem to worry about money! Life is a breeze for them!” This meta moment is as good a summation as any of the point of Stan Lee’s career. He believed in heroes with the proverbial feet of clay: character flaws, disabilities, personal problems. “What’s wrong with me?” Stan would have Peter Parker lament after another big win as Spider-Man was followed by bad news on the home front. “I’ve defeated some of the most powerful supervillains of all time—without batting an eye! But, why do I have so much trouble—just managing my own life—?” This was chief among the reasons Steve Ditko left Amazing Spider‑Man in 1966: as a fierce Objectivist, Ditko demanded that heroes be flawless. He’d accepted that Peter Parker might not fully have his act together in high school, because adolescence is a time for learning. But after Ditko formally took over plotting duties on the book, he wrote Peter Parker the college man the way Ayn Rand would have. E.g., in issue #38 he has Gwen Stacy think, “No matter what the others say, there’s something so strong—so proud about Peter Parker—!” That turned out to be Ditko’s last issue: to Stan Lee, that wasn’t Spidey, and so they had to part ways. Kirby stuck around at Marvel a few years longer, but his partnership with Lee had also been more one of creative tension than a shared vision. Kirby didn’t want to tell stories about the superhero as flawed everyman. He also didn’t want to tell stories about the superhero as Nietzschean Übermensch. Jack Kirby wanted to tell stories about gods.

The comics shop I went to when I lived in Massachusetts was called Modern Myths, and the owners were far from the first to observe that superhero comics just put a new coat of paint on ancient tales of warriors with extraordinary abilities. The Justice League and the Avengers, the argument went, were updated versions of mythological pantheons—an argument that didn’t require much of a leap of imagination given that a founding member of the Justice League was Hippolyta’s daughter and a founding member of the Avengers was Odin’s son. It’s like when the creationists who don’t understand speciation ask “If humans evolved from monkeys, why are there still monkeys??” If superheroes are the new mythological gods, why do both Marvel and DC also have the old mythological gods running around? In Marvel’s case, Stan Lee said that he was concerned that the strongest characters in the embryonic Marvel Universe were monsters, the Thing and the Hulk, and he wanted a nobler figure to stand at the top of the power scale. But it was a paradox: a human who could go toe to toe with the Hulk could hardly be considered human anymore. Thus, he hit upon the idea of using a mythological god: Thor. He and Jack Kirby launched Thor in Journey Into Mystery in 1962, but they were very busy and moved on to other things after just seven issues. They were still busy at the end of 1963; of the issues with a November cover date, Stan and Jack worked together on Avengers #2, Fantastic Four #20, Sgt. Fury #4, Strange Tales #114, Tales to Astonish #49, and X‑Men #2—a heavy workload for a writer and a staggering one for a penciler—but they still made room in their schedules to also crank out issue #98 of Journey Into Mystery, to which they had returned a month earlier. They’d seen what other writers and artists were doing with Thor’s book, and both thought it demonstrated the truth of the old saw about doing something right meaning doing it yourself. Kirby started drawing a second Thor feature called Tales of Asgard, which set aside the concept of a man in modern New York with the power of a Norse god, and instead just retold medieval myths in the Kirby style. And it wasn’t long before the primary feature began to resemble the backup strip, with Thor spending less time on Earth and more time in Asgard, or in the realms of trolls and giants, or on alien planets. The premise of the character had once been that a man named Don Blake had found Thor’s hammer and possessed the Norse god’s power so long as he held the hammer. Over the course of his first several issues, though, he started behaving more and more as though Thor was who he actually was while in that form. After Kirby returned and hit his stride, Blake was almost forgotten: he appeared in Journey Into Mystery #124, and then not again until issue #138, over a year later, by which point the name of the series had changed to Thor. In between, the only other human character in the series, love interest Jane Foster, was written out of the book, and Thor’s romantic attentions immediately turned to the Asgardian warrior goddess Sif. Then Thor #159 (cover date 1968.12) reveals that Don Blake had never even been real, but was a vessel that Odin had whipped up, filled with false memories, and transferred Thor’s spirit into in order to teach him humility. So there were no truly human characters left to get in the way of gigantic panel after gigantic panel with armies of gods, monsters, and aliens blasting each other, Kirby Krackle bouncing off chunky armor in all the colors of the rainbow. Sure, maybe the audience was more interested in human-level stories like Peter Parker’s love triangle with Gwen Stacy and Mary Jane Watson, but this sort of thing was Kirby’s passion. As Kirby reduced the number of titles he was working on from “all of them” to just two, one of the books he stuck with until he left Marvel in 1970 was Thor.

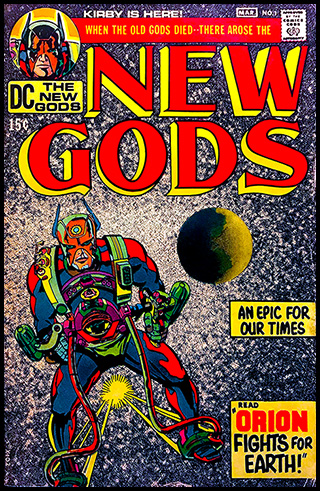

The other was Fantastic Four, and look at some of those storylines I mentioned earlier. The Inhumans? A society of creatures with extraordinary abilities who lived in a hidden city in the mountains, with a king and a queen and a court, who had dalliances with mortals? Few missed the parallels to the Olympian pantheon. Galactus, the cosmic planet-eater? “I went to the Bible” for inspiration, Kirby explained, and the Silver Surfer was this space god’s herald angel. Or consider Him, created by a group of scientists who set out to create a “supreme new race”, then quail when their prototype does indeed possess “power without limit”: “This planet of humans is not for me,” this golden demigod declares, “not yet—not till another millinium [sic] has passed!” Annoyed that Lee was getting the credit for all these creations, both among the public and among the corporate higher-ups, Kirby finally made a break with Marvel and jumped to DC. The title with which he made his big splash was perhaps a bit on the nose:

In New Gods and its companion titles Mister Miracle and Forever People, Kirby embarked upon a saga of a war between the good space deities of the planet New Genesis and the evil space deities of the planet Apokolips. These characters had names like Big Barda, Granny Goodness, and Funky Flashman. Yeah. Kirby had been eager to show the world what his work looked like without Stan Lee adulterating it, and, uh, yeah, now we were seeing it. Oh, I guess I forgot to mention Virman Vundabar. And Glorious Godfrey. Anyway, the idea was that this would be an self-contained epic with a beginning, a middle, and an ending, which could then be collected into a single tome and sold in reputable bookstores. At least, that was Kirby’s idea. It was not DC’s idea. These series sold well, at first—so why on earth would the company allow them to end, voluntarily? They could be a source of profits for decades to come! No, Kirby was instructed, he would not be permitted to bring this cosmic war to a final resolution—he’d done the beginning, and now the middle was to last forever. Oh, and surely these creations could be tied into the existing DC properties? Like, that main villain, Darkseid—he’d be a perfect bad guy for the Justice League! Let’s make that happen! The result: narrative momentum came to a halt, sales collapsed, and New Gods and Forever People were both canceled with issue #11. Whoops! Jack Kirby returned to Marvel in 1976.

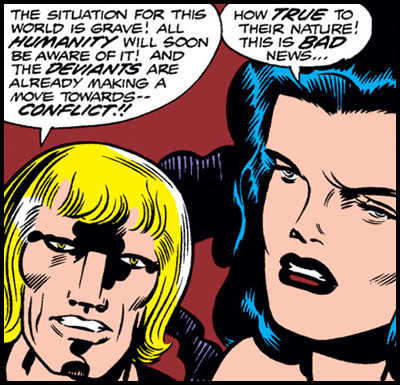

There he tried to launch yet another pantheon. Introducing… the Eternals! “WHEN GODS WALK THE EARTH!” read the tag line at the top of the new Eternals series, whose debut issue was titled “The Day of the Gods” for good measure. The premise: there is a race of space gods that look much like Galactus, only without Galactus’s humanlike face; basically, they look like huge Kirbytech robots, the size of mountains. These space gods, the Celestials, came to Earth hundreds of thousands of years ago and used their technology to force forward the evolution of primates, who diverged into three species: humans; Eternals, who “bred few in number and were immune to time and death”; and the gargoyle-like Deviants. Now the Celestials have returned to monitor the planet for fifty years and judge whether its inhabitants shall be permitted to survive. There’s not really a ton of narrative momentum after that: we see a few failed schemes to kill a celestial (one by the Soviets, one by the Deviants, one by an evil Eternal), and apart from that, the series is mostly just a matter of introducing new characters and building out the universe of Eternals.

Because Eternals was originally not supposed to take place in the Marvel Universe. Jack Kirby, from the reports I’ve seen, hated shared continuity and the restrictions it imposed on any given story. Example: while I am thankful to say that the Eternals don’t have names like “Granny Goodness”, their names are embarrassing in a different way. You’ve heard of such figures from Greco-Roman mythology as Zeus, Athena, Mercury, Icarus, Ajax, and Circe? Pick up an issue of Eternals and you’ll be introduced to Zuras, Thena, Makkari, Ikaris, Ajak, and Sersi. And instead of Olympus they live in “Olympia”. The explanation the series gives is that the Eternals interacted with humans in prehistory and got incorporated into ancient myth. But in the Marvel Universe, the Greco-Roman gods are real! Stan Lee had opted to put Norse mythology front and center because he thought it would be fresher to the readership than another rehash of Homer and Ovid, but it wasn’t long before Pluto was a recurring Thor villain and Hercules was an Avenger. So Eternals initially does seem as though it takes place somewhere else in the Marvel multiverse than the mainstream MU, Earth‑616. When the Eternals (and one Deviant) reveal themselves to the public, people react as though they’re the first set of superhumans ever to do so, rather than the hundred thousandth. The series plays with the question a bit: issue #13 promises that the following issue will guest-star the Hulk, but that Hulk turns out to be a robot, and a crowd jokes about how “Marvel’s characters are running amuck [sic]!” Of course, the ersatz Hulk didn’t appear just for laughs—it was an attempt to goose sales, which were poor. The late 1970s were a tough time for the American comics industry in general, and Jack Kirby wasn’t exactly a hot new name. His style had always had a touch of the grotesque to it, and now that touch had become a full-on grope:

That’s Ikaris and Sersi in Eternals #3. I guess Picasso might have approved of the eye placement on Sersi, but I don’t know who would have endorsed Ikaris’s rectangular nose. Maybe Mondrian. In any case, Eternals didn’t even make it to issue #20. Kirby didn’t get to do any wrap-up, either—the book was canceled that abruptly. The dangling plotlines were picked up by Marvel’s original continuity expert, Roy Thomas (whom Kirby despised, and had lampooned as “Houseroy” over at DC). Thomas spent nearly as many issues of Thor weaving the Eternals into the Marvel Universe as Kirby had spent on their original series—and, again, it’s kind of silly. Take a character like Quicksilver of the Avengers: he’s a great example of the way superheroes follow in the tradition of mythological gods, as “quicksilver” is another name for mercury, and the character is a speedster just like the god Mercury. But Mercury was the Roman name for the Greek god Hermes, and Hermes also exists in the Marvel Universe. Now we add Makkari, a genetically engineered superhuman who claims to have inspired human belief in that god? How many versions of the same archetype do we need? The thing is, it seemed like nearly all of Marvel’s rising generation of writers—Steve Englehart, Mark Gruenwald, Roger Stern, etc.—thought that this sort of thing was what constituted good storytelling. It was just issue after issue of assembling the puzzle pieces of Marvel continuity. The first storyline involving the Eternals I ever encountered was Avengers #246–248 (cover dates 1984.08–10), the point of which was to tie the Eternals to Jim Starlin’s Titans, and as a ten-year-old who had only been reading comics for a year, I was less than enthralled that Stern and Gruenwald had found a way to weave together storylines from 1972 and 1976.

At the end of that storyline, most of the Eternals unite in the Uni‑Mind (merging into a giant brain, as established by Kirby in Eternals #11–14) and head out into space, whittling the concept of the Eternals down to “about half a dozen Greek god knockoffs hang around in a mostly empty hidden city”. Even that is overselling it: at least the Greek gods had personalities. Among the Eternals, well, Sersi is sassy and likes parties a lot, and Sprite is an insufferable brat. Thena is the female one who isn’t Sersi. The rest are just a bunch of interchangeable Stump Hugelarge and Cliff Beefpile types. Anyway, in 1985 they received a new limited series based on the premise that the Deviants take advantage of the Eternals’ reduced numbers to try to conquer the world, apparently under the impression that the Avengers wouldn’t notice. Maybe the most noteworthy thing about this series is that, even though it was slated from the get-go to run for only twelve issues, editor-in-chief Jim Shooter hated it enough that he replaced the creative team midway through. There’s some butterfly effect there: Walt Simonson finished it up, and when he was hired to take over Avengers and replace the current cast with his own lineup, he selected one of the Eternals for it: the Forgotten One, a.k.a. Gilgamesh. Simonson then immediately left the book for reasons I recounted here. John Byrne took over, and right from his first issue he wrote Gilgamesh as a doofus. That was Avengers #305; in #307, he has Gilgamesh stupidly get knocked into a coma. In #308 the team takes Gilgamesh to Sersi’s apartment to see whether she can heal him; in #310, it turns out that he has to stay in Olympia to recover, and Captain America and Thena discuss the possibility of another Eternal taking his place; by #314, Sersi is on the team. And she would be an Avengers mainstay for years—1989 to 1994, to be precise—as the book largely revolved around a soap opera involving her and Dane Whitman, the Black Knight. And here’s an odd bookend: in 1994, Marvel bought Malibu Comics, which published a line called the “Ultraverse”. Marvel tried to keep that line alive by transferring some of its own characters over to it, and Sersi and the Black Knight were the ones chosen. So, for a while at least, the most frequently published of Jack Kirby’s Eternals ended up outside the Marvel Universe after all.

There were further attempts to make the Eternals work. Neil Gaiman, who had revived an earlier Kirby co-creation with some success, was given an Eternals limited series in 2006 in which Sprite has blanked out the Eternals’ memories of being Eternals, which both hit the reset button and set a direction for future Eternals stories (find more Eternals and wake ’em up!). Sprite gets a little bit of depth of characterization in the bargain—he’s the one who has spent millennia as an eleven-year-old, and Gaiman has him pretty resentful about it. In 2008, this series was followed up by an ongoing one written by a couple of TV guys, which was canceled before its issue count even broke into the double digits. Taking the hint, Marvel didn’t do much with the Eternals in the 2010s, and Jason Aaron even killed them off in an issue of Avengers, but with an Eternals movie in the pipeline, the company tapped Kieron Gillen to rework the concept and find a niche for the Eternals that wouldn’t make them redundant with the Inhumans and the Asgardians and however many other pantheons Marvel had kicking around. I passed on this 2021 series because the art was really not for me, but it was a big deal at the time. It crossed over in a major way with the Avengers, with the X‑Men, with everyone really—heck, I have an issue of Amazing Spider-Man, a title I was not collecting, in which the Eternals v5 crossover plot had a Celestial following Peter around in the form of Gwen Stacy, just because I really liked that story. But even that big push couldn’t get the readership invested in the Eternals, no matter how well reimagined they were. The series was canceled after just twelve issues.

Meanwhile, over in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, the Eternals movie came out—and having now watched it, I’d say that, for the most part, it improved on the comics. Improvement number one: it is much clearer about the premise. Jack Kirby had pretty much wanted to spend the remainder of his career drawing endless battles between angels and devils, and the premise he set forth in Eternals was just handwavy stuff to make that happen. Why did the Celestials create the Eternals and the Deviants? Unclear! Why are the Deviants so bellicose? At first we’re told it’s merely because the Deviants were a “destructive failure” and that “constant war” is their “lot”. Then it’s because they’re tyrannical slavers who’d once “used man as one would a beast of the field”. Then it’s because they want to drive the Eternals into space and free themselves from the hegemony of the Celestials. Meanwhile, what do the Eternals want? We see them meditating on mountaintops and are told that historically they have “probed the universe with their minds”. So why are they now fighting the Deviants? In Ajak’s case, it’s because he’s a devoted servant of the Celestials, so their enemies are his enemies. But Zuras, patriarch of the Eternals, is not so fond of the Celestials, telling Olympia’s majordomo (named, in typical Kirby fashion, Domo) that the Celestials’ actions “may not be to our liking”. As for Ikaris, it’s very simple: “One cannot make peace with your species!” he tells a Deviant. “If you find reason in war—then I say—TO BATTLE!” So everyone’s motivations are all over the place and it’s kind of confusing. By contrast, the movie straightforwardly sets out the premise right up front. The Celestials created the first stars from the stuff of the primeval cosmos, which led to the universe we know, and life. But then the Deviants arose, preying on intelligent species—and the Deviants aren’t little troll men here, but monsters that look like the dark beasts from the Upside Down in Stranger Things. So the Celestials recruited the Eternals, immortal heroes from the planet Olympia, to visit inhabited planets and wipe out the Deviants. Our little group of ten Eternals arrived on Earth seven thousand years ago; five hundred years ago, they eradicated the last Deviant. Since then they’ve gone their separate ways, doing their own thing and watching the centuries slip by. Now the Deviants have returned and it’s time to get the gang back together. Like I said, it’s very straightforward. It’s also a pack of lies—but because the film is clear about what’s going on, the revelation of the truth behind the MCU version of the Eternals had me thinking “Wow!”, when normally this sort of thing just has me thinking “Huh?”

I was also wowed by the sheer spectacle on offer. Eternals is a visual extravaganza, from the cosmic stuff (Arishem the Celestial inspires the appropriate amount of awe, and depicting the total destruction of a planet sure has come a long way since my day) to the tour of planet Earth in many times and places: since the Eternals have been here since the dawn of civilization, we see Babylon, the Gupta Empire, Tenochtitlan during the Spanish conquest, Hiroshima after the bomb dropped, and more. All of this is much more relevant to my interests than the car chases and dragon-fighting ninjas of Shang-Chi. That movie was all about the punching and the kicking, and while there is of course some of that here, the Eternals have a wider variety of powers, from Phastos’s technomancy to Druig’s mind control to Ikaris’s eye beams to Sprite’s illusions to Sersi’s matter transmutation—and while in the comics she was prone to turn men into pigs, as in the Odyssey, here the filmmakers made sure that Sersi would always use her powers for something beautiful: turning a crashing bus into rose petals, that sort of thing. Even the costumes are great: they capture the spirit of the Kirby costumes without copying them, and hit the sweet spot of looking good in live action while still being unmistakably superhero costumes. On the story side… I mean, it’s not literature, and there are plenty of moments that are clunkers (the comic relief needs work, for instance), but the plot twists landed, and generally so did the characters. The ten Eternals had distinct personalities—though the one with the vaguest characterization was the one with the most personality in the comics, namely Sersi, because here she’s the lead rather than the saucy supporting character who hits on Captain America while Ikaris and Zuras woodenly recite Big Talk. They made for a more pleasant ensemble to spend time with than the Avengers or the Defenders, and the movie teased multiple storylines for sequels to follow—Sersi is involved with Dane Whitman as in her Avengers tenure, and at the end he unboxes the ebony blade he carries as the Black Knight; also, Starfox shows up—so I was looking forward to what came next.

Except apparently no sequels have been made because the movie flopped. Even with a movie better than most MCU fare, people just don’t care about the Eternals. Ah well. At least Jack Kirby’s fans have the satisfaction of knowing that Stan Lee died before he could do a cameo in a movie dedicated to Kirby’s solo project.

|

|

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tumblr |

this site |

Calendar page |

|||