[Matt Fraction, Allan Heinberg, Stan Lee, Mark Millar, David Mack, Brian Bendis, Devin Grayson, David Aja, Jim Cheung, Joe Quesada, John Romita Sr., J. G. Jones, Don Heck, Bryan Hitch, and] Jonathan Igla, 2021

I already talked about Hawkeye’s first few appearances in my article on the Black Widow, with whom he was closely linked for most of the 1960s. The short(‑ish) version: Clint Barton is the world’s greatest archer, but in 1964 that just makes him a carnival act, and not a very popular one. “Big deal! So he hit the target!! What a crummy act!” “C’mon! Get that bum off the stage and bring on the dancin’ girls!” Envious that superheroes get all the glory, Barton decides to become one—“Hawkeye, the Marksman!”—but when he foils a robbery, the cops think that he’s the robber, and Hawkeye, thinking “They’d never believe I’m innocent!”, makes a run for it. (As a kid I thought this was a lame plot device, but nowadays it reads to me like an accurate depiction of American policework and a pretty sensible response on Clint’s part.) By a fluke of happenstance, randomly driving by is the Black Widow, back in the days when her costume consisted of a black beehive hairdo and a fur coat, and she gives him a ride. Instantly smitten, Hawkeye carries out several of the schemes the Widow puts into action at the behest of her “communist masters”, fighting Iron Man several times. Then he breaks into Avengers Mansion and ties up Jarvis the butler… only to announce that he had never intended to become a villain and actually wants to join the team. Avengers being a silly book in this era, the other members instantly agree.

Hawkeye’s first role as an Avenger was as the brash young hothead in “Cap’s Kooky Kwartet”, the much lower-powered second generation of the team. With only short breaks here and there, he would stick around for several more generations—nearly twenty years, real time, during which his characterization didn’t change much. Depending on the writer and the situation, in any given issue he would land somewhere on the continuum from “lovable rascal” to “impulsive dumbass”. Then, in 1983, Hawkeye got his first solo book, a four-issue limited series written and drawn by Mark Gruenwald—a bit of a stunt, since Gruenwald was not known as an artist. The two big developments in that series are that Hawkeye loses most of his hearing, deliberately deafening himself so that he won’t be susceptible to the bad guy Crossfire’s sonic weapon, and that he gets married. See, DC Comics had its own archer, Green Arrow, whom Denny O’Neil had paired up with the Black Canary back in 1969. That seemed like a winning combination, Gruenwald thought, so why not pair up Hawkeye with a blonde acrobatic fighter who dressed in black and had an avian nom de guerre? And it just so happened that Marvel had one of those kicking around! Mockingbird has a very interesting history of her own, evolving from Dr. Barbara Morse to S.H.I.E.L.D. Agent 19 to the Huntress before adopting the code name she would stick with—but going into it all would undermine my attempt to make this the short(‑ish) version. Anyway, not long after Hawk and Mock got hitched, the Avengers started up an affiliated team on the west coast, with Hawkeye tapped as the leader—“the character who used to be the immature one has to be the adult in the room” became Hawkeye’s primary theme during this period. Steve Englehart wrote West Coast Avengers for the title’s first few years, and the way he split up the happy couple is kind of ironic in light of the way Hawkeye would be reworked in the years to come. Mockingbird is kidnapped by a character called the Phantom Rider, who drugs and, it is heavily implied, rapes her. When she is freed from his control, she confronts him; in the ensuing fight, he winds up dangling from the edge of a cliff, and instead of pulling him up, Mockingbird lets him fall to his death. For some time she lies to Clint about this, but he eventually finds out what happened, and their marriage is doomed. It’s not just the lies that Hawkeye can’t take: he’s portrayed as a hero from a more innocent time, who insists that Avengers don’t kill. While there were hints at a potential reconciliation, they became academic when Roy Thomas killed off Mockingbird in ’93 and she stayed dead for over fifteen years, real time. Then came a bunch of bullshit with Space Phantoms and pocket universes and stuff that I’ve discussed in past articles but will skip here. By ’98, Hawkeye was back in a familiar role, now leading the Thunderbolts, a group of supervillains trying (with varying degrees of commitment) to reform. He stayed in that role until ’03. The following year, Brian Bendis killed him.

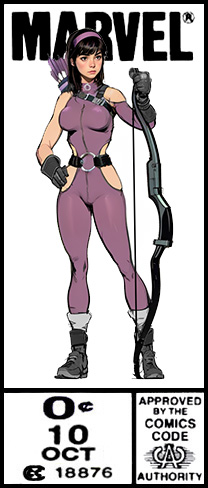

Unlike Mockingbird, Hawkeye didn’t stay dead for long. But a lot happened in his absence. For one, the Avengers briefly disbanded. Stepping in to fill the void was a new group, which the title of their series named the Young Avengers. DC Comics had scored a huge hit in the 1980s with the Teen Titans, a group that had originally consisted of a bunch of DC superheroes’ young sidekicks: Robin, of course, but also Kid Flash, Aqualad, Wonder Girl, Green Arrow’s sidekick Speedy, and more. But after the Golden Age, when Captain America went on all his adventures with his “young ally, Bucky” (as I discussed here) and the Human Torch was joined by his young partner Toro, Marvel superheroes didn’t have teenage sidekicks. Thus, the initial quartet of Young Avengers are all new characters who adopt names that sound like they might be the original Avengers’ sidekicks: Patriot, Asgardian, Hulkling, and Iron Lad. But on one of their first missions, trying to stop gunmen from holding up a society wedding, they need to be rescued by one of the bridesmaids. Her name is Kate Bishop.

Kate’s backstory was pieced together over the course of many years in many different series, not all of which I have read. But as I understand it, it goes like this. Kate Bishop grew up exceedingly wealthy… because her father was a New York City crimelord. While her older sister was happy to spend Dad’s blood money, Kate worked off her guilt volunteering at soup kitchens and whatnot. Then one night she was violently raped in Central Park. One way she dealt with her trauma was to become extremely proficient at self-defense, with particular expertise in antiquated weapons such as the sword and the bow. On this basis, Kate was able to join up with the Young Avengers despite having no powers. And since Avengers Mansion was not in use circa 2005, the Young Avengers were able to raid it for supplies (since one of their new members was Ant‑Man’s daughter and had the entry codes); since Hawkeye and Mockingbird were both dead, Kate was able to take all their weapons. She didn’t have a code name for a while, but in Young Avengers #12 Captain America convinces her to become the new Hawkeye. After all, the old one is dead. That was cover date 2006.08. Five months later, Clint Barton was revived.

So what do you do when you come back from the dead and someone else is using your superhero name? Well, here is where we have to jump back a few years and over to the Marvel Knights Daredevil series, which I discussed in the middle of my aforementioned Black Widow article. Kevin Smith only lasted eight issues on that title; taking over with issue #9 (cover date 1999.05) was David Mack, known primarily for his art, heavy on collage, watercolor splashes, and triangles—but here Joe Quesada drew most of the interiors while Mack handled the scripting chores. Daredevil is blind—his main power is that his other four senses have been heightened to superhuman degrees. Mack introduced a character, Maya Lopez, who is deaf. She has the same power as the Taskmaster: “photographic reflexes”. She can duplicate any physical feat she has seen even once. Her father had worked for Daredevil’s arch-nemesis and Marvel’s top mob boss: the Kingpin, Wilson Fisk. But mob bosses aren’t great to work for, because they often kill you. This was the fate of Maya’s father. But after pulling the trigger on his underling, the Kingpin decided to honor his dying wish—that Fisk see to the welfare of young Maya, whose powers turned out to make her a prodigy. When grown, she wants revenge on her father’s killer, whom her benefactor helpfully identifies as Daredevil. Maya tries to kill him several times. When she discovers that Daredevil could not actually have been the killer and that the Kingpin therefore must have been, she shoots Fisk in the head, which somehow leaves him blinded but with no other visible injuries. Cut back to ’05 and New Avengers #11. Captain America is concerned about the Hand, the organization of necromantic ninjas whose importance in Daredevil’s roster of villains can be summed up by the fact that in the Daredevil TV show, the Kingpin was the big bad of season one and the Hand was the big bad of season two. Daredevil says that he can’t join the Avengers, but Cap talks about how he has spent periods wearing other costumes, and we see that following this conversation there is a ninja in a distinctive black costume fighting the Hand, so clearly we’re supposed to think that this is Daredevil. It turns out to be Maya Lopez, a revelation whose impact is severely blunted by the way Bendis, who is abysmal at plotting, mishandles the sequence of hints. At this point she normally goes by Echo; in this costume the cover and the recap blurbs call her Ronin, but Bendis being Bendis, he never puts that information in the actual story. In any case, she gives up the identity after three issues, so it’s available for Clint to take up when he returns from the dead. He’s Ronin until the middle of 2010. That was the start of “The Heroic Age”, a linewide initiative in which Marvel titles promised a return to familiar versions of characters and sunnier storylines. In Hawkeye’s case, that meant the reappearance of his classic costume and a string of limited series that drew upon 1980s plot threads—like, here’s Hawkeye in the year of our blorb two thousand and ten, hanging around with Mockingbird and taking on Crossfire and the Phantom Rider. But “The Heroic Age” branding concluded with cover date 2012.04. Six months later came the landmark Hawkeye series, volume four, that became the primary influence for this TV series and defined both Hawkeyes for a new era.

Before I get to that, though, I should probably talk about yet another Hawkeye. In the year 2000, Bill Jemas was named Marvel’s new publisher, as the company clawed its way back from its 1996 bankruptcy. He thought that the company was hobbled by what was then nearly forty years of continuity. For instance, Spider-Man’s original concept was that while DC’s heroes were bland, successful adults in their civilian identities, Peter Parker was a fifteen-year-old nerd with a lot of personal problems. But since 1962 he had grown up and was now one of those successful adults—married to a supermodel, even. Attempts had been made to remedy this: the infamous Clone Saga of the 1990s had originally been intended to send Peter off into the sunset and bring in a blank slate called Ben Reilly as the new Spider-Man. The fan reaction derailed these plans. Four of Marvel’s longest-running series (including Fantastic Four) had been canceled and rebooted with new #1 issues in 1996, but these too had their original continuity restored just a year later as this “Heroes Reborn” project imploded. What Jemas did was start a new comic, Ultimate Spider-Man, in which Peter Parker was fifteen… without doing anything about the version of Peter Parker who was pushing thirty. The two versions of Spider-Man existed simultaneously, one in the mainstream Marvel Universe (Earth‑616), the other in the new “Ultimate Universe” (Earth‑1610). Sales were strong enough out of the gate that several other Ultimate titles received the green light. One of these was called The Ultimates, and, well, let me put it this way. At the same time this series was launched, DC was in the middle of a series called Just Imagine in which Stan Lee and a slew of big-name artists set forth new premises for DC’s stable of characters. Just Imagine Stan Lee with John Buscema Creating Superman, for instance, has an alien named Salden getting stranded on Earth, which hasn’t developed the technology he needs to return home. Nor will it ever be able to do so until problems such as poverty and global conflict are wiped out, so Salden takes on the name Superman and vows to use his powers to foster the utopian civilization that can make the necessary advances. The Ultimates was essentially the opposite: Just Imagine NOT Stan Lee but Instead a Callow British Edgelord Creating the Avengers.

The Marvel Cinematic Universe version of the Avengers owes as much to Mark Millar’s Ultimates as to the original Avengers series. The idea that the Avengers start as a S.H.I.E.L.D. project, with a Nick Fury modeled on Samuel L. Jackson, is straight out of the Ultimate line. Five of the six original MCU Avengers are, admittedly, closer to the MU versions than to the Ultimate ones… but the notable exception is Hawkeye. Ultimate Hawkeye is neither a lovable rascal nor an impulsive dumbass; he’s a dour S.H.I.E.L.D. assassin transferred to the superhero team from the black ops division. He also has a wife (Laura) and three kids. All of these details match the cinematic version. A slight divergence is that in the MCU, Hawkeye loses his family to the Thanos Snap, and he basically turns into the Punisher in response, taking on the identity of Ronin and launching a bloody vendetta against the underworld. But five years later, the Thanos Snap is undone and Clint’s family is restored, so all’s well that ends well. In Ultimates 2 #7, by contrast, Hawkeye’s family is just flat-out murdered, and when he goes into his Punisher phase, it’s not as Ronin but as a sort of knockoff of the Daredevil villain Bullseye: not only does he stick a target on his forehead like Bullseye, but in #10, Millar has Hawkeye‑1610 pull a very Bullseye stunt, freeing himself from the torture chair he’s strapped to by tearing off his own fingernails and using his superhuman marksmanship to flick them into the throats of the bad guys. Like I said, Millar is an edgelord. Another divergence is that in the MCU, Hawkeye’s sons are named Nathaniel and Cooper, whereas in The Ultimates, they are Lewis and Callum. Like I said, Millar is a British edgelord.

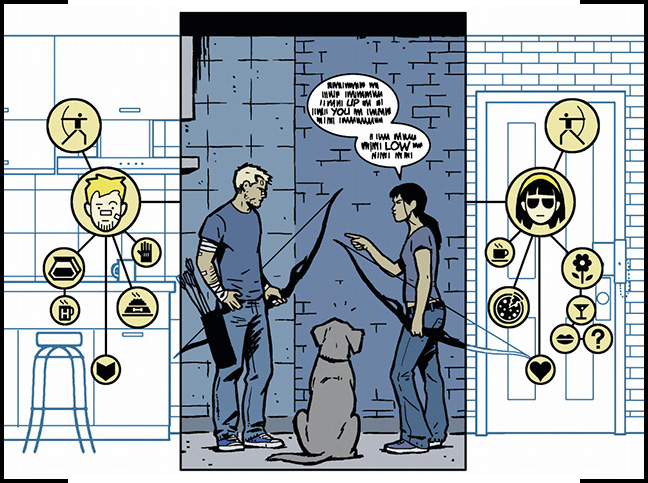

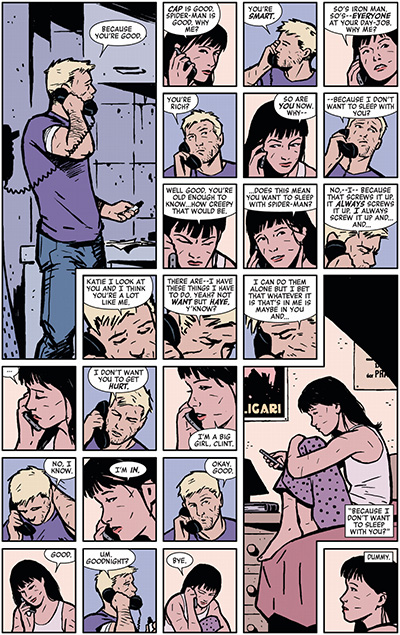

So let’s talk Hawkeye v4. On the formal level, writer Matt Fraction and artist David Aja broke ground by basically bringing the technique of Chris Ware, with his postage-stamp-sized iconographic panels, to superhero comics. Here’s a sample:

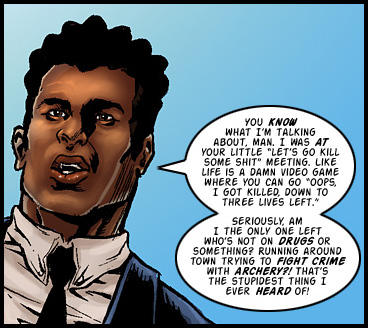

And then here’s a portion of a page from Hawkeye v4 #11, told from the perspective of Lucky the Pizza Dog: